[dropcap letter=”L”]

ast week we reported on Xavier Gonzàlez’s blog, a collection of night-time chronicles about his current stories as a cabbie in Barcelona. But cabbies and their anecdotes also allow us to look back and travel in time without stepping out of a taxi.

In the US, for example, the latest special issue of the 50th anniversary of New York Magazine included a series of fine images by Joseph Rodríguez, a former cabbie (1977-1985) turned documentary photographer, always had a camera with him. As a result, spontaneous portraits of unusual quality, immortalizing the day by day experience in Harlem or Bronx, with buskers or the hustle and bustle of sado clubs in a downbeat Meatpacking. There are also photographs of extreme social injustice of the time, and some portraits of his clientele, like a couple who have been married for 45 years: she complains that her husband snores, he snaps back at her saying that she keeps farting all night long.

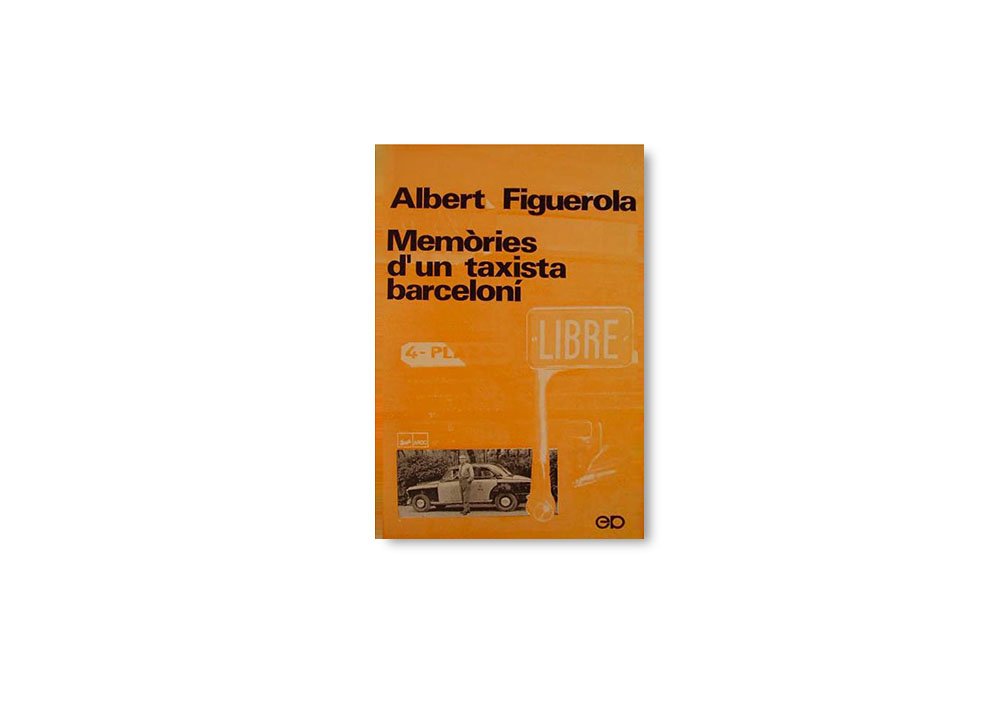

A few months before Franco’s death, Catalonia saw the publication of Memòries d’un taxista barceloní (Memories of a Barcelona cabbie), a book of anecdotes by Albert Figuerola –written when he was seventy years old, an “honorary cabbie”–, a collection of decades of experiences and anecdotes in a cab and the famous people he had driven around in his taxi, like Charles Aznavour, Mary Santpere or Ernest Lluch.

Figuerola was born in the north-eastern region of Catalonia, in Empordà, and after getting by doing little jobs in Barcelona, a winning ticket from the national lottery gave him the opportunity to buy his first taxi, a Citroën Torpede. This was back in 1924, a time of big cars and bonanza –for cabbies it definitely was– with a clientele of cigar-smoking, tie-wearing gentlemen and long hours at the taxi rank, chatting away. As a result of the war, those dream-like vintage cars were collectivized, and their characteristic yellow colour changed into anarchist red. Figuerola lost his taxi and never got into one again until 1956, first driving a Citroën Rosalia that belonged to one of his acquaintances, and later buying a SEAT 1400, with a license that would last to his retirement.

Figuerola was born in the north-eastern region of Catalonia, in Empordà, and after getting by doing little jobs in Barcelona, a winning ticket from the national lottery gave him the opportunity to buy his first taxi, a Citroën Torpede. This was back in 1924, a time of big cars and bonanza –for cabbies it definitely was– with a clientele of cigar-smoking, tie-wearing gentlemen and long hours at the taxi rank, chatting away. As a result of the war, those dream-like vintage cars were collectivized, and their characteristic yellow colour changed into anarchist red. Figuerola lost his taxi and never got into one again until 1956, first driving a Citroën Rosalia that belonged to one of his acquaintances, and later buying a SEAT 1400, with a license that would last to his retirement.

His philosophy was interesting: Figuerola sustains that a cab is a second home, a temporary shelter of sorts that taxi drivers offer their clients. This is why many of them feel strongly urged to make it cosy (now, they are even offering wifi). He claims that if the passenger feels comfortable, a taxi becomes a confessional, a private space where clients give free rein to everything they feel. This results eventually in an unlikely relationship of trust with someone you have just met (I mean someone who will not ask you to recite three Our Fathers afterwards).

Cabs have always been places for romance, recalls Figuerola, from the day a cabbie lowered the flat to the present time. Memòries d’un taxista barceloní is a collection of the hustle and bustle in several meublés –back then, already cabbies used to get commissions– and also couples who, with the excuse of being together and having the luxury of a discrete space, they would say “all the way to Molins de Rei and we’ll arrange the fee”, and all the driver had to do was driving them around for as long as they pleased. Those times, “a cab driver has to be deaf, blind and mute”, states the author.

With regard to foreigners, Figuerola’s advice is more demanding than ever before: cabbies are like tour guides for tourists, because they become ambassadors on wheels around the city. To this date, many tourists believe that a cabbie is the native local citizen who they will interact with longer, such small talk can determine, mostly, the type of impression a visitor will have about his visit to Barcelona.