Everything seems to indicate that agriculture and cattle-raising stand on...

Who is primarily responsible for the so-called "greenhouse effect"? What...

The most popular use of supercomputation in industry is the...

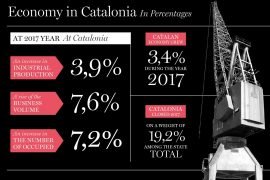

The Catalan economy grew 3.4% in 2017 according to estimates...

Its spin-off, Peptomyc, is immersed in its second clinical trial,...

With constant innovation and a unique system of traceability and...

The Sant Martí facility wins the award shortly after its...

In 2050 the self-driving car will be a reality that...

There is no need, anymore, to go to Silicon Valley...

Currently, e-commerce generates 53 million purchases per year in Catalonia,...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

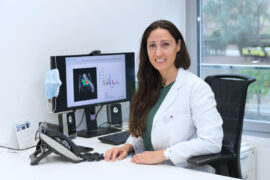

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”Y”]

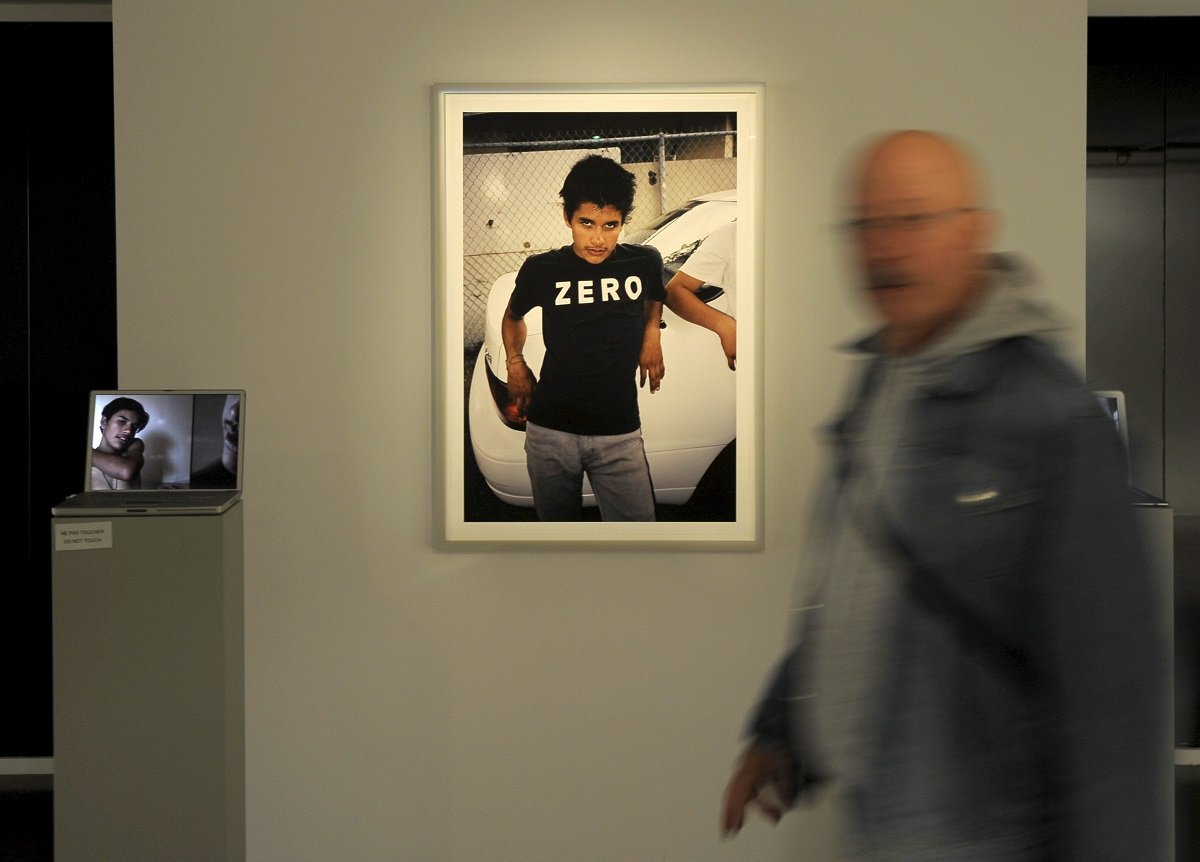

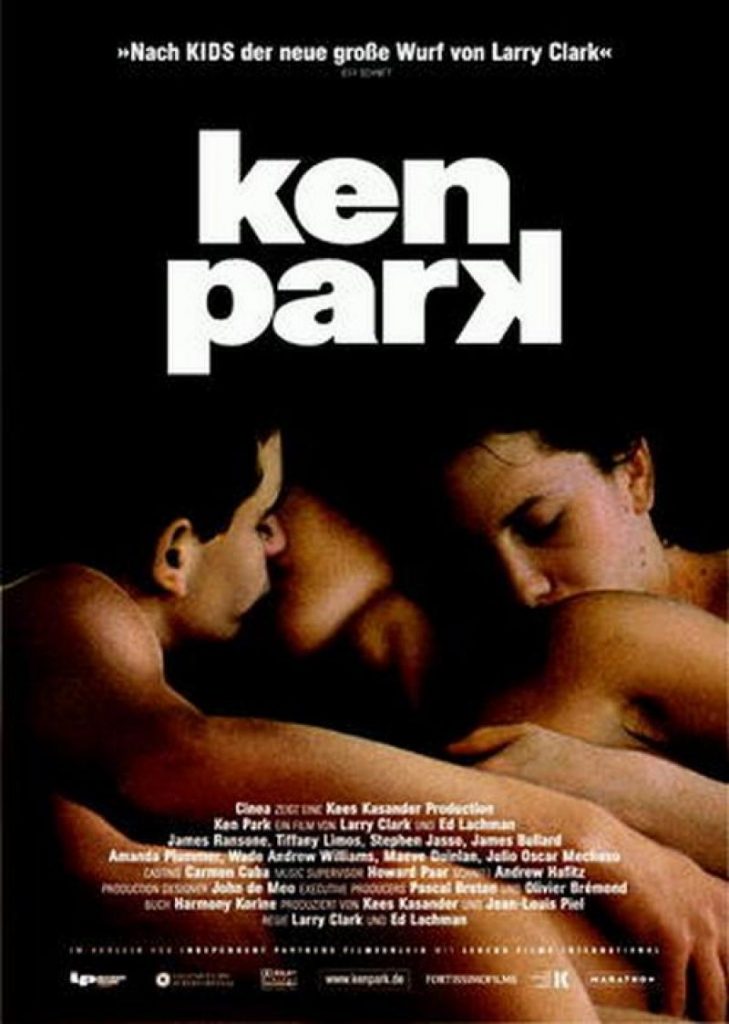

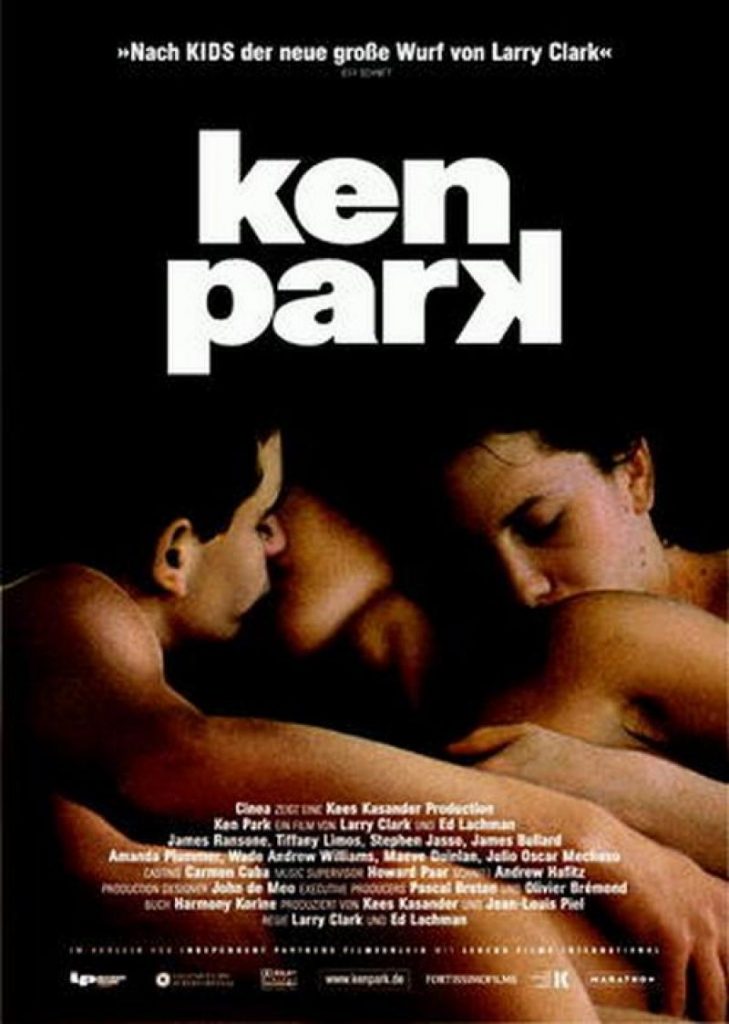

ou’re wrong if you try to make it seem like I’m doing it to stir up controversy. I’m only trying to be honest and to explain the truth about life”. These are Larry Clark’s words taken from his website. Clark is photographer and filmmaker born in Oklahoma, one of those states where Donald Trump trounced Hillary Clinton’s Democrats. His work is a portrait of adolescents born between the 80s and the early 21st century. Larry Clark is mostly known for the uproar caused by his first film, Kids (1995). Since then, he has made 7 more, and of them I would particularly highlight Ken Park (2002) because I saw it in a cinema in Helsinki where I lived for a few months far from home and the anchors of good behaviour. Now that the American artist is 75 years old and life must beckon him to sweeten his bitter fantasies which he has been bestowing over his lengthy career, like nosegays of dead flowers, perhaps he’d like to sip some tea every now and then.

Experts don’t agree on the dates of the core generation in Larry Clark’s oeuvre: the one after the children of the Baby Boomers from post-World War II. Some call them Generation Y, but the more up-to-date name is millennials

There is a tea brand which stands out from the competition because it offers optimistic messages on the tabs dangling from the end of the string. One of the ones I like the best says something like: there was no one like you, there is no one like you, and there won’t be anyone like you. Zen philosophy promotes this way of presenting the individual in the global context. And it rings true to me. However, reality tells us that with the exception of singularities, the targets of the economic markets determine the fate of those of us belonging to a specific time period, even though sometimes it is the result of failed experiments. This is why we speak about generations, set and subsets of identities that have been forged and respond by bringing their own voice to art, thinking, relations with the environment, interpersonal relationships, etc.

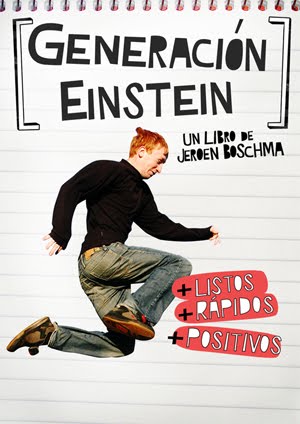

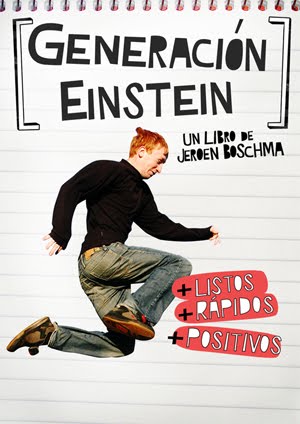

Experts don’t agree on the dates of the core generation in Larry Clark’s oeuvre: the one after the children of the Baby Boomers from post-World War II. Some call them Generation Y, but the more up-to-date name is millennials. Regardless, in 2008, when the concept of Gen Y had not yet spread and millennials had not even been coined, a book fell into my hands by Jeroen Boschma, a Dutch consultant trained in art, in which youths who are at most 30 years old today were the object of analysis: Generation Einstein: Smart, Social and Superfast. Communicating with Young People in the 21st Century (Pearson, 2006). It contained the conclusions of 20 years of study and conversations that the communication agency Keesie, of which Boschma is a cofounder, conducted with youths born after 1988. Everything pointed to the fact that a major shift was underway compared to the previous generation, distinguished by emotional highs and lows and pessimism, an ideological void, traditional values and the dichotomy between feeling like the heirs of the family or the fierce desire to ditch it.

Everything pointed to the fact that a major shift was underway compared to the previous generation, distinguished by emotional highs and lows and pessimism, an ideological void, traditional values and the dichotomy between feeling like the heirs of the family or the fierce desire to ditch it

Eight months ago, I decided to leave everything behind in Barcelona and travel. This has allowed me to get in touch with the women and men who were the target of Boschma’s theoretical study and Clark’s emotional interpretation. We have practised yoga together in an ashram Rishikesh, I have seen them determined to tackle the Anapurna with a kid strapped to their backs, and I have witnessed them gathered to watch the wonders of the Milford Sound in a rickety van. I’ve compared myself to them and I’ve felt like a victim and trivial. I have heard, and even recorded, yearnings to get away from the clichés learned as successful models to follow.

In Catalonia, the men and women of Clark and Boschma are a rarity. This is the consequence of a secular delay in our cultural evolution compared to the youths of central and northern Europe, Canadians, Americans and some Asians

Boschma’s theoretical results in 2006 hinted that those youths’ model of life revolved around the present and nothing more. I have found that this is true, and that they have made a virtue of it: they avoid expectations. I have also perceived aftereffects of the macabre portrait by Larry Clark: the youths who are between the ages of 18 and 30 today do not in any way share our structured system corseted by discipline. The outcome of their acts is not the outcome of effort but of their very existence. They are self-taught by conviction, reject models that do not suit them, and are successful – oh, the paradox! – because they don’t pursue success. These men and women are pointing towards a new cognitive revolution. They are ready to accelerate a worldwide shift in direction which would fully renew the Western patterns of living. Given this scenario, I can only feel hopeful.

However, I do regret having to note two things. The first is that in Catalonia, the men and women of Clark and Boschma are a rarity. This is the consequence of a secular delay in our cultural evolution compared to the youths of central and northern Europe, Canadians, Americans and some Asians. This is not a flip comment; it is the reflection of a fearfulness whose origins lie in the vivid roots of the Franco regime. The second is that this generation has learned to live, and so far – at least among Europeans – I have not seen a desire to latch onto politics. They understand it, but they find it boring, insignificant and useless. To them it would be like ceasing to live, and they’re right.

[dropcap letter=”Y”]

ou’re wrong if you try to make it seem like I’m doing it to stir up controversy. I’m only trying to be honest and to explain the truth about life”. These are Larry Clark’s words taken from his website. Clark is photographer and filmmaker born in Oklahoma, one of those states where Donald Trump trounced Hillary Clinton’s Democrats. His work is a portrait of adolescents born between the 80s and the early 21st century. Larry Clark is mostly known for the uproar caused by his first film, Kids (1995). Since then, he has made 7 more, and of them I would particularly highlight Ken Park (2002) because I saw it in a cinema in Helsinki where I lived for a few months far from home and the anchors of good behaviour. Now that the American artist is 75 years old and life must beckon him to sweeten his bitter fantasies which he has been bestowing over his lengthy career, like nosegays of dead flowers, perhaps he’d like to sip some tea every now and then.

Experts don’t agree on the dates of the core generation in Larry Clark’s oeuvre: the one after the children of the Baby Boomers from post-World War II. Some call them Generation Y, but the more up-to-date name is millennials

There is a tea brand which stands out from the competition because it offers optimistic messages on the tabs dangling from the end of the string. One of the ones I like the best says something like: there was no one like you, there is no one like you, and there won’t be anyone like you. Zen philosophy promotes this way of presenting the individual in the global context. And it rings true to me. However, reality tells us that with the exception of singularities, the targets of the economic markets determine the fate of those of us belonging to a specific time period, even though sometimes it is the result of failed experiments. This is why we speak about generations, set and subsets of identities that have been forged and respond by bringing their own voice to art, thinking, relations with the environment, interpersonal relationships, etc.

Experts don’t agree on the dates of the core generation in Larry Clark’s oeuvre: the one after the children of the Baby Boomers from post-World War II. Some call them Generation Y, but the more up-to-date name is millennials. Regardless, in 2008, when the concept of Gen Y had not yet spread and millennials had not even been coined, a book fell into my hands by Jeroen Boschma, a Dutch consultant trained in art, in which youths who are at most 30 years old today were the object of analysis: Generation Einstein: Smart, Social and Superfast. Communicating with Young People in the 21st Century (Pearson, 2006). It contained the conclusions of 20 years of study and conversations that the communication agency Keesie, of which Boschma is a cofounder, conducted with youths born after 1988. Everything pointed to the fact that a major shift was underway compared to the previous generation, distinguished by emotional highs and lows and pessimism, an ideological void, traditional values and the dichotomy between feeling like the heirs of the family or the fierce desire to ditch it.

Everything pointed to the fact that a major shift was underway compared to the previous generation, distinguished by emotional highs and lows and pessimism, an ideological void, traditional values and the dichotomy between feeling like the heirs of the family or the fierce desire to ditch it

Eight months ago, I decided to leave everything behind in Barcelona and travel. This has allowed me to get in touch with the women and men who were the target of Boschma’s theoretical study and Clark’s emotional interpretation. We have practised yoga together in an ashram Rishikesh, I have seen them determined to tackle the Anapurna with a kid strapped to their backs, and I have witnessed them gathered to watch the wonders of the Milford Sound in a rickety van. I’ve compared myself to them and I’ve felt like a victim and trivial. I have heard, and even recorded, yearnings to get away from the clichés learned as successful models to follow.

In Catalonia, the men and women of Clark and Boschma are a rarity. This is the consequence of a secular delay in our cultural evolution compared to the youths of central and northern Europe, Canadians, Americans and some Asians

Boschma’s theoretical results in 2006 hinted that those youths’ model of life revolved around the present and nothing more. I have found that this is true, and that they have made a virtue of it: they avoid expectations. I have also perceived aftereffects of the macabre portrait by Larry Clark: the youths who are between the ages of 18 and 30 today do not in any way share our structured system corseted by discipline. The outcome of their acts is not the outcome of effort but of their very existence. They are self-taught by conviction, reject models that do not suit them, and are successful – oh, the paradox! – because they don’t pursue success. These men and women are pointing towards a new cognitive revolution. They are ready to accelerate a worldwide shift in direction which would fully renew the Western patterns of living. Given this scenario, I can only feel hopeful.

However, I do regret having to note two things. The first is that in Catalonia, the men and women of Clark and Boschma are a rarity. This is the consequence of a secular delay in our cultural evolution compared to the youths of central and northern Europe, Canadians, Americans and some Asians. This is not a flip comment; it is the reflection of a fearfulness whose origins lie in the vivid roots of the Franco regime. The second is that this generation has learned to live, and so far – at least among Europeans – I have not seen a desire to latch onto politics. They understand it, but they find it boring, insignificant and useless. To them it would be like ceasing to live, and they’re right.