The German city of Freiburg has become an example of...

The festival redoubles its commitment to offering a wide variety...

There are things that only happen once in a lifetime....

Experiencing a match day in the Wanda Metropolitano Stadium allows...

In 2050 the self-driving car will be a reality that...

CosmoCaixa commemorates the half century of the arrival to the...

The Earth from space, those other corners of the universe,...

The unremitting human emancipation from nature –transformed into “culture”– is...

The twin-cherry brand, originally established in Sitges in 1967 and...

The unremitting human emancipation from nature –transformed into “culture”– is...

Como bien nos recordaba Irene Vallejo en su Manifiesto por...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

[dropcap letter=”R”]

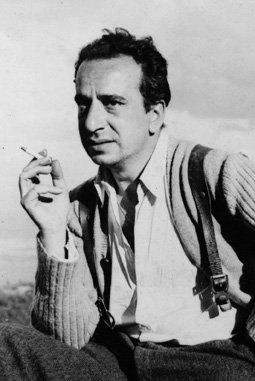

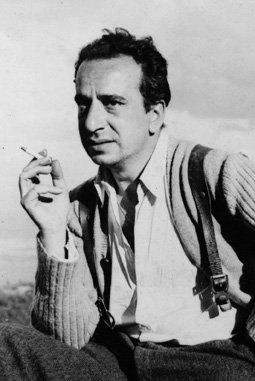

Re-reading and discovering Joan Sales as a hit of catalan novel is always worth it. It has been mainly in the last 10 years that Uncertain Glory —his great novel, one of the best about the Spanish Civil War— has experienced a new boom in its reception and consideration inside and outside Catalonia. The precarious institutional year dedicated to him in 2012, on the centenary of his birth, served, unlike with Salvador Espriu’s celebration, to regenerate his readership and activate a couple of relevant projects. While Montserrat Casals’ biography about the writer was lagging behind —and was left unfinished because of a lethal cancer— what came out was the theatre adaptation, spearheaded by director Àlex Rigola, in theatres in May and June 2015 in the small room —not a puny detail that should not be overlooked— of the National Theatre. During springtime, its cinema version was released. The film, directed by Agustí Villaronga, condensed in less than two hours the 600 page-long novel: from 2012, the epilogue, more ghostlike and elegiac, is sold separately under the title El vent de la nit [The wind of the night]. In the last five years, apart from more Catalan reprints, Uncertain Glory has been warmly welcome in its German, Romanian and English translation. The latter was shortlisted by ‘The Economist’ as one of the ten most relevant fiction books in 2014.

Nevertheless, Uncertain Glory still receives, from time to time, occasional reductionist attacks. A recent attack intended to disqualify it as a by-product of Gironella. We could not understand it as unfair criticism because —even worse— it evidences the ignorance of its author. There are some who, from preconceived and prejudiced standpoints, denies the remarkable literary worth of Joan Sales’ novel. Some have even written that the prose in Uncertain Glory is mediocre. The formal and ethical consistency of the novel can easily refute this view. Unlike a remarkable percentage of fiction published in Catalan between 1950 and early 1970s, the first version of the book received the award Joanot Martorell and dates back to 1956; the fourth and final version was released in 1971. Joan Sales’ prose is fast, direct and contemporary. Uncertain Glory is a skilful combination of ideas and feelings, whose author manages to blend the disenchanted solemnity of the soliloquies pronounced by Juli Soleràs with the clear tone —charmingly innocent— of the letters written by Trini Milmany and the sombre descriptions of Aragonese villages and the atmosphere at the front line from Lluís de Brocà. The conversations are unprecedentedly mighty and powerful. The stories told by the soldiers are funny in parts, like in Cruells’ sleepwalking attack that nearly gets him killed; in parts, the stories freeze you to death, like when they discover the body of a donkey during one of Soleràs’ expeditions on a cliff, from where, when he was young, peeped at a foreign couple kissing each other: intrigued by the corpse’s swallowing, the young man punctures it with a sea reed, and on withdrawing it, the hole produced a whistling sound similar to “a mouth full of saliva”, a disturbing image just like the comment about the mouth of the male lover, and describes him as someone who has “magnificent teeth”, “white and defiant like only true savages can have”.

In the last five years, apart from more Catalan reprints, Uncertain Glory has been warmly welcome in its German, Romanian and English translation. The latter was shortlisted by ‘The Economist’ as one of the ten most relevant fiction books in 2014

In Uncertain Glory, the horror at the sight of the exhumed mummified corpses of the priest by the anarchists, on display before an altar of an Aragonese monastery, representing a macabre last wedding celebrated in that sacred space —the groom “has been stuck with a candle” (…) grotesquely laid out— lives with Trini’s conversion to Christianity, “ethereal and hazy”. Should anyone search for uncritical and blindfolded snapshots in Uncertain Glory, they will find nothing of the sort: nevertheless, faith is at stake on contrasting it to war and also on trying to maintain a fictional and perversely hurtful relationship. “Coming from the obscene, moving into the macabre”, admits Juli Soleràs in more than one occasion. Quizzical, idealist and contradictory, Soleràs embodies the antihero of the book, capable of moving from one side to another while Lluís, instead of thinking about Trini and his son, is obsessed by the “painful aura” of Carlana. His disenchantment —dragging from childhood, and symbolically revealed through his toothache— allows him to question party ideologies and stagnant affiliations. At this moment in time, defining such many-nuanced writer to ultracatholic or parafascist —for example— is just as biased as saying that French literature celebrates quality over ideology. This would be like moving onto an imaginary battlefield where verbal bullets are shot willy-nilly, for no reason whatsoever, and whose victim, whatever side we take, will always be good literature.

[dropcap letter=”R”]

Re-reading and discovering Joan Sales as a hit of catalan novel is always worth it. It has been mainly in the last 10 years that Uncertain Glory —his great novel, one of the best about the Spanish Civil War— has experienced a new boom in its reception and consideration inside and outside Catalonia. The precarious institutional year dedicated to him in 2012, on the centenary of his birth, served, unlike with Salvador Espriu’s celebration, to regenerate his readership and activate a couple of relevant projects. While Montserrat Casals’ biography about the writer was lagging behind —and was left unfinished because of a lethal cancer— what came out was the theatre adaptation, spearheaded by director Àlex Rigola, in theatres in May and June 2015 in the small room —not a puny detail that should not be overlooked— of the National Theatre. During springtime, its cinema version was released. The film, directed by Agustí Villaronga, condensed in less than two hours the 600 page-long novel: from 2012, the epilogue, more ghostlike and elegiac, is sold separately under the title El vent de la nit [The wind of the night]. In the last five years, apart from more Catalan reprints, Uncertain Glory has been warmly welcome in its German, Romanian and English translation. The latter was shortlisted by ‘The Economist’ as one of the ten most relevant fiction books in 2014.

Nevertheless, Uncertain Glory still receives, from time to time, occasional reductionist attacks. A recent attack intended to disqualify it as a by-product of Gironella. We could not understand it as unfair criticism because —even worse— it evidences the ignorance of its author. There are some who, from preconceived and prejudiced standpoints, denies the remarkable literary worth of Joan Sales’ novel. Some have even written that the prose in Uncertain Glory is mediocre. The formal and ethical consistency of the novel can easily refute this view. Unlike a remarkable percentage of fiction published in Catalan between 1950 and early 1970s, the first version of the book received the award Joanot Martorell and dates back to 1956; the fourth and final version was released in 1971. Joan Sales’ prose is fast, direct and contemporary. Uncertain Glory is a skilful combination of ideas and feelings, whose author manages to blend the disenchanted solemnity of the soliloquies pronounced by Juli Soleràs with the clear tone —charmingly innocent— of the letters written by Trini Milmany and the sombre descriptions of Aragonese villages and the atmosphere at the front line from Lluís de Brocà. The conversations are unprecedentedly mighty and powerful. The stories told by the soldiers are funny in parts, like in Cruells’ sleepwalking attack that nearly gets him killed; in parts, the stories freeze you to death, like when they discover the body of a donkey during one of Soleràs’ expeditions on a cliff, from where, when he was young, peeped at a foreign couple kissing each other: intrigued by the corpse’s swallowing, the young man punctures it with a sea reed, and on withdrawing it, the hole produced a whistling sound similar to “a mouth full of saliva”, a disturbing image just like the comment about the mouth of the male lover, and describes him as someone who has “magnificent teeth”, “white and defiant like only true savages can have”.

In the last five years, apart from more Catalan reprints, Uncertain Glory has been warmly welcome in its German, Romanian and English translation. The latter was shortlisted by ‘The Economist’ as one of the ten most relevant fiction books in 2014

In Uncertain Glory, the horror at the sight of the exhumed mummified corpses of the priest by the anarchists, on display before an altar of an Aragonese monastery, representing a macabre last wedding celebrated in that sacred space —the groom “has been stuck with a candle” (…) grotesquely laid out— lives with Trini’s conversion to Christianity, “ethereal and hazy”. Should anyone search for uncritical and blindfolded snapshots in Uncertain Glory, they will find nothing of the sort: nevertheless, faith is at stake on contrasting it to war and also on trying to maintain a fictional and perversely hurtful relationship. “Coming from the obscene, moving into the macabre”, admits Juli Soleràs in more than one occasion. Quizzical, idealist and contradictory, Soleràs embodies the antihero of the book, capable of moving from one side to another while Lluís, instead of thinking about Trini and his son, is obsessed by the “painful aura” of Carlana. His disenchantment —dragging from childhood, and symbolically revealed through his toothache— allows him to question party ideologies and stagnant affiliations. At this moment in time, defining such many-nuanced writer to ultracatholic or parafascist —for example— is just as biased as saying that French literature celebrates quality over ideology. This would be like moving onto an imaginary battlefield where verbal bullets are shot willy-nilly, for no reason whatsoever, and whose victim, whatever side we take, will always be good literature.