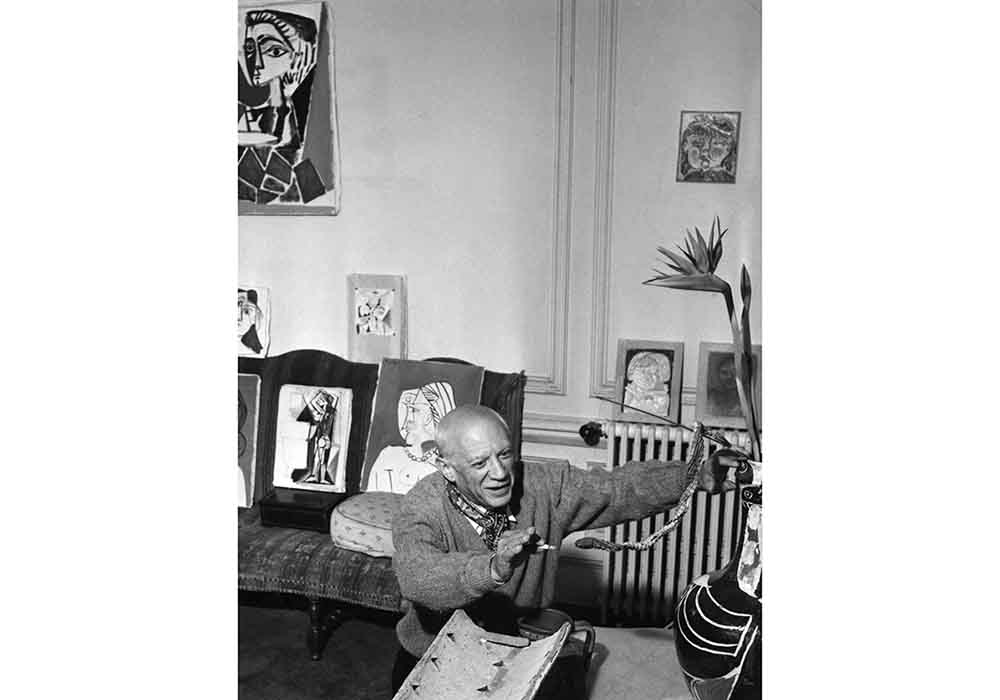

Guernica was a demigod, canonized while still alive: if he were still alive, Picasso would have a crowd of paparazzi permanently parked in front of his studio at the Rue des Grands-Augustins in Paris or at the villa La Californie in Cannes, reporting live on the latest young woman he would have inveigled.

The Picassian myth is like the Minotaur he often painted: sacrifice and flesh are required to keep it at bay. In exchange for drawing astronomical prices at auctions and millions of visitors to museums, the beast demands new exhibitions and exacts unprecedented advances. That is why, while we wait for the highly anticipated exhibition of the breeches in which he painted, we will make do with Picasso’s Kitchen that has just opened at the museum in Carrer de Montcada, where we will learn everything about his relationship with victuals, except the name of his cook.

Peculiarly, the cliché about Picasso’s voracity, of the greed with which he devoured pictorial styles—with an estimated 50,000 plus works, which is soon said—clashes with the apparent frugality with which he ate: little and healthily, and drank rarely. Broth for dinner, and at noon he had enough with an omelette and vegetables in season: leeks, cauliflower or radishes in winter, cucumbers, peppers and tomatoes in summer. And rabbit and [Catalan botifarra] sausages, and when he was by the beach, octopus, anchovies and grilled sardines: I imagine that the Malaga espetos [or skewered fish] would be his Proustian madeleine.

The exhibition is full of still lifes that reflect those meagre tables, with fruit, crusts of bread and perhaps a glass of wine, of a realist, cubist or literary stamp—literary since the shopping lists for the Montmartre grocer’s are also on display. There are masterpieces such as Young Boy with Lobster—Mr. Picasso in a Festa Major (patron saint’s festival) inflexion—with tuck always present throughout his lifetime: there is the kitchen in Malaga painted by the prodigal child of 15, and a little further along, the sculpture-assemblages of the Valauri period, where the sexagenarian Picasso throws pottery dishes and attaches ceramic fishlings, soles or fried eggs with botifarra.

Bars and restaurants are also to be seen, particularly the Quatre Gats [café] in Barcelona, where besides attending social gatherings, the young Pablo Ruiz designed a menu, a dish-of-the-day poster and a “food-and-drink-served-at-all-hours” propaganda pamphlet. Of course, at the Quatre Gats everything must have been booze and chatter, because they say that the food was inedible, and Josep Pla came to write that “servings were always pure illusion of the spirit.” Picasso’s Kitchen also speaks of Cal Tampanada in Gósol, the mythical hostel in the Berguedà [mountain region] where, while the artist reinvented himself in Spring 1906, poor Fernande survived on potatoes and vegetables, because she could not suffer the civet of hare or the mountain stews. “There is nothing in this region,” she wrote, grieved, to Apollinaire, “not a patissier, nor a confectioner, nor a baker, nor a mercer: nothing at all.”

The exhibition is sponsored by Ferran Adrià, because it is impossible to speak of cuisine and art in Barcelona without quoting today’s great genius. No matter that Picasso, a lover of simple cuisine, the opposite of artifice, would have ruffled his nose at the hyper-botifarra with spheriphied white beans: the commissioners consider that just as the Demoiselles d’Avignon caused a revolution in painting, the Bullinian textured vegetable stew did the same for cuisine. And in order to leave no doubt, those who want to sample Picasso’s cuisine can do so at several restaurants in Barcelona, for example at The Serras Hotel, where chef Marc Gascons has prepared a five-course Picasso menu, including a Cubist apple.

Featured images:

1. Pablo Picasso artist at his Cannes villa. Photo by Pictorial Press Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

2. Catalog of the exhibition “Picasso’s Kitchen”.