2017 saw the consolidation of three trends: larger rounds of...

Its spin-off, Peptomyc, is immersed in its second clinical trial,...

Three Catalan restaurants – El Celler de Can Roca (2),...

Alzheimer's is, like the human brain itself, a mystery to...

CosmoCaixa commemorates the half century of the arrival to the...

The importance of the logistics and transport industry is unquestionable....

The new Movistar Car service provides a Wi-Fi network in...

You would never say that Mari Carmen Tous is 85...

Barcelona has become a desired destination for investors, beyond the...

The two artists embrace each other in a joint exhibition...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

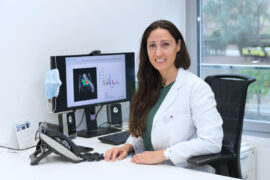

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”R”]

udyard Kipling, the author of The Jungle Book, died on the 18th of January. Fifteen days before, he had said that he was not afraid of dying. A magazine reported his statements, but in a rather peculiar way. Without beating around the bush, it published his obituary early, much to the surprised of the presumed victim. “I’ve just read that I’ve died. Don’t forget to cancel my subscription.” No matter how absurd this response seems, it actually shows astonishing logic. How could he keep ties with a publication that claims that the subscriber is no longer alive, and therefore could not read it? Not to mention the low reliability of the news that the magazine published…

Recently there was a media frenzy over the story of a prisoner who had been presumed dead but awoke in the morgue, just as he was about to be autopsied. Such an exceptional and terrifying situation

Kipling’s sarcastic remarks dates from 1936, and since then there have been plenty of other dead people who have come to life again. Recently there

was media frenzy over the story of a prisoner who had been presumed dead but awoke in the morgue, just as he was going to be autopsied. Such an exceptional and terrifying situation has been described as traumatic for the subject and most likely – we can speculate without fear of erring – for the person who perceived movement and sounds in an inert body.

REALITIES OF THE PHANTASM

A being that is a non-being, the spirit of someone who has not fully left the world but instead remains to threaten living people or remind them of the possibility of the end which inevitably awaits them. Or perhaps, with their paradoxical reality. In David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997), the Mystery Man who is pulling all the strings in the story is in two places at once because he is actually in neither, because he isn’t of this world.

A being that is a non-being, the spirit of someone who has not fully left the world but instead remains to remind people of the possibility of the end

The morbid fascination that terror films arouse should be viewed as a controlled approach to extreme violence, and ultimately to the ultimate mystery of life. This approach takes place under laboratory conditions, without the risk of really suffering from irreversible damage. This tendency is not just of our time. Instead, its roots lie in the origins of the cinematographic genre, whose quintessence lies in the possibility of making the invisible visible, in making shadows real, and in featuring the creatures of the night. The success of vampire films back in the early days of cinema expresses and sublimates an atavistic unease which, as such, transcends time. We could recall Nosferatu (1922) by F. W. Murnau, a creature with a horrifying magnetism, or Vampyr, the more refined and metaphysical version by the Danish director C. T. Dreyer.

SEEING TRANSLUCENT BODIES

Not only does that 1932 film narrates the lethal activity of a vampire-witch, but the viewer also witnesses one of the most fascinating splits in the history of film. Using the double-exposure technique, a translucent apparition rises out from the body. The young vampire hunter, affected by the loss of blood after a transfusion, faints and leaves himself to witness his own funeral. He sees the preparations from inside the coffin with a disoriented gaze. And the camera – his failed eyes – captures a low-angle shot of the entire landscape that goes by on the way to the cemetery: how he crosses the threshold of the door, the waving tree canopies, the church bells ringing and the sacred building left behind.

The camera captures a low-angle shot of the entire landscape that goes by on the way to the cemetery

After this, the main character, seated on the same bench from which he disappeared, regains consciousness. The narrative ambiguity is fantastic and disturbing, because the dead man’s vision, though unlikely, becomes cinematographically possible. With a sensibility closer to today’s, in Hereafter (2010) Clint Eastwood wanted to narrate the possibility of life after death, which the main character can perceive. The return of many people who have been on death’s doorway, equipped with information on their dead family members, which they are somehow able to find out, feeds the rumours of the existence of a bright light at the end, where lives converge without any time distinction

A FEW LAST WORDS

From here it seems essentially complex to confirm that extreme, and some funny situations have also questioned this transcendence. Socrates confessed that he knew nothing about what awaited him once he was dead. Nonetheless, his last speech, after drinking hemlock but still awaiting its effects, is worth recalling: “Remember, Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. Do pay it. Don’t forget.” The god of health is given an offering either to pay off a debt or earn his blessing. This surprising end, which Plato transcribes in Phaedon, contrasts with the sentence he transcribes in the early The Apology of Socrates, which is no less memorable: “The hour of departure has arrived, and we go our ways. I to die, and you to live. Which is better God only know.”

“Am I dying or is this my birthday?”

There are many “last words” that reveal an inspired strangeness. The story has it that when Lady Astor, a close friend of Georg Bernard Shaw, was prostrate on her deathbed, she awoke once and asked everyone present: “Am I dying or is this my birthday?” It may be a rhetorical question, a justified blunder or a last joke, but the fascinating thing about the anecdote is that it is a dreamlike blurring of the boundaries that separate what is known and not known about life, and especially about death.

In this sense, we know that poor Segismundo confused the artifice of his jail cell with the apparent fiction of palace life. His awakening to reality is necessarily processed as a trick, which could be viewed as an invitation to think beyond reason and accept that there is no less reality in dream than in consciousness, in wakefulness. This is why the dreamlike melody by Nancy Sinatra You Only Live Twice sounds about right, as it states that we are fated to live two lives: “One life for yourself, and one for your dreams”.

WHEN THE END IS THE BEGINNING

Yet even more inspiring is the hypothesis posited by a film like Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) This hypothesis is on the human way of perceiving time. Perhaps only we perceive that life goes by in a linear fashion, with a past and a future, a before and an after. Perhaps other forms of life view time in a circular fashion, or through a simultaneity that does not spatially distinguish past from future. When approaching beings who have come from outer space, the main character of this film physically lives experiences from the past – which she doesn’t even remember – and at a decisive moment in the plot she finds the answer in the future, which hasn’t yet happened.

[dropcap letter=”R”]

udyard Kipling, the author of The Jungle Book, died on the 18th of January. Fifteen days before, he had said that he was not afraid of dying. A magazine reported his statements, but in a rather peculiar way. Without beating around the bush, it published his obituary early, much to the surprised of the presumed victim. “I’ve just read that I’ve died. Don’t forget to cancel my subscription.” No matter how absurd this response seems, it actually shows astonishing logic. How could he keep ties with a publication that claims that the subscriber is no longer alive, and therefore could not read it? Not to mention the low reliability of the news that the magazine published…

Recently there was a media frenzy over the story of a prisoner who had been presumed dead but awoke in the morgue, just as he was about to be autopsied. Such an exceptional and terrifying situation

Kipling’s sarcastic remarks dates from 1936, and since then there have been plenty of other dead people who have come to life again. Recently there

was media frenzy over the story of a prisoner who had been presumed dead but awoke in the morgue, just as he was going to be autopsied. Such an exceptional and terrifying situation has been described as traumatic for the subject and most likely – we can speculate without fear of erring – for the person who perceived movement and sounds in an inert body.

REALITIES OF THE PHANTASM

A being that is a non-being, the spirit of someone who has not fully left the world but instead remains to threaten living people or remind them of the possibility of the end which inevitably awaits them. Or perhaps, with their paradoxical reality. In David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997), the Mystery Man who is pulling all the strings in the story is in two places at once because he is actually in neither, because he isn’t of this world.

A being that is a non-being, the spirit of someone who has not fully left the world but instead remains to remind people of the possibility of the end

The morbid fascination that terror films arouse should be viewed as a controlled approach to extreme violence, and ultimately to the ultimate mystery of life. This approach takes place under laboratory conditions, without the risk of really suffering from irreversible damage. This tendency is not just of our time. Instead, its roots lie in the origins of the cinematographic genre, whose quintessence lies in the possibility of making the invisible visible, in making shadows real, and in featuring the creatures of the night. The success of vampire films back in the early days of cinema expresses and sublimates an atavistic unease which, as such, transcends time. We could recall Nosferatu (1922) by F. W. Murnau, a creature with a horrifying magnetism, or Vampyr, the more refined and metaphysical version by the Danish director C. T. Dreyer.

SEEING TRANSLUCENT BODIES

Not only does that 1932 film narrates the lethal activity of a vampire-witch, but the viewer also witnesses one of the most fascinating splits in the history of film. Using the double-exposure technique, a translucent apparition rises out from the body. The young vampire hunter, affected by the loss of blood after a transfusion, faints and leaves himself to witness his own funeral. He sees the preparations from inside the coffin with a disoriented gaze. And the camera – his failed eyes – captures a low-angle shot of the entire landscape that goes by on the way to the cemetery: how he crosses the threshold of the door, the waving tree canopies, the church bells ringing and the sacred building left behind.

The camera captures a low-angle shot of the entire landscape that goes by on the way to the cemetery

After this, the main character, seated on the same bench from which he disappeared, regains consciousness. The narrative ambiguity is fantastic and disturbing, because the dead man’s vision, though unlikely, becomes cinematographically possible. With a sensibility closer to today’s, in Hereafter (2010) Clint Eastwood wanted to narrate the possibility of life after death, which the main character can perceive. The return of many people who have been on death’s doorway, equipped with information on their dead family members, which they are somehow able to find out, feeds the rumours of the existence of a bright light at the end, where lives converge without any time distinction

A FEW LAST WORDS

From here it seems essentially complex to confirm that extreme, and some funny situations have also questioned this transcendence. Socrates confessed that he knew nothing about what awaited him once he was dead. Nonetheless, his last speech, after drinking hemlock but still awaiting its effects, is worth recalling: “Remember, Crito, we owe a cock to Asclepius. Do pay it. Don’t forget.” The god of health is given an offering either to pay off a debt or earn his blessing. This surprising end, which Plato transcribes in Phaedon, contrasts with the sentence he transcribes in the early The Apology of Socrates, which is no less memorable: “The hour of departure has arrived, and we go our ways. I to die, and you to live. Which is better God only know.”

“Am I dying or is this my birthday?”

There are many “last words” that reveal an inspired strangeness. The story has it that when Lady Astor, a close friend of Georg Bernard Shaw, was prostrate on her deathbed, she awoke once and asked everyone present: “Am I dying or is this my birthday?” It may be a rhetorical question, a justified blunder or a last joke, but the fascinating thing about the anecdote is that it is a dreamlike blurring of the boundaries that separate what is known and not known about life, and especially about death.

In this sense, we know that poor Segismundo confused the artifice of his jail cell with the apparent fiction of palace life. His awakening to reality is necessarily processed as a trick, which could be viewed as an invitation to think beyond reason and accept that there is no less reality in dream than in consciousness, in wakefulness. This is why the dreamlike melody by Nancy Sinatra You Only Live Twice sounds about right, as it states that we are fated to live two lives: “One life for yourself, and one for your dreams”.

WHEN THE END IS THE BEGINNING

Yet even more inspiring is the hypothesis posited by a film like Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival (2016) This hypothesis is on the human way of perceiving time. Perhaps only we perceive that life goes by in a linear fashion, with a past and a future, a before and an after. Perhaps other forms of life view time in a circular fashion, or through a simultaneity that does not spatially distinguish past from future. When approaching beings who have come from outer space, the main character of this film physically lives experiences from the past – which she doesn’t even remember – and at a decisive moment in the plot she finds the answer in the future, which hasn’t yet happened.