Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

Its first 'boutique' in Barcelona will open on the ground...

According to the United Nations, attracting the financial system is...

Take a deep breath. Alright? We are going to talk...

“Science is alive and it’s part of culture. Science is...

In critical times, it is fair to determine the relevance...

In its fourth edition, the Audiovisual Talent Week, maintains the...

The rate of caravan registrations has increased by 347% in...

The audiovisual sector has a motto that will always prevail:...

Producing and marketing homes within demand-based pricing will continue to...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”K”]

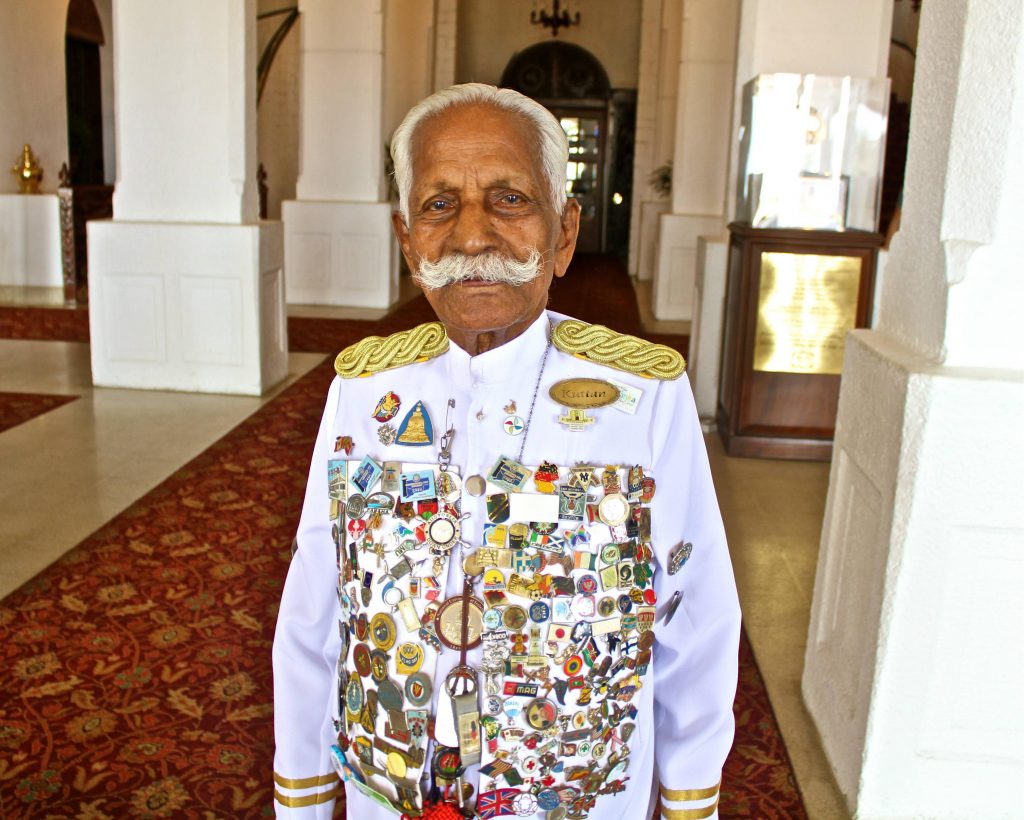

ottarappu Chattu Kuttan is dead. I do not recognize him by his name, but by a photo published in an English paper. Dressed in black, his chest decorated with badges and a bushy moustache, sunken eyes and aquiline nose, he was waiting at the staircase, his hands folded, for the guests of Hotel Galle Face, in Sri Lanka, the oldest colonial hotel in Asia. Galle Face is one of the thousand places one should visit before dying, according to a book and the website of our booking —which had conveniently erased with photoshop the horrible buildings showing up on the back.

I remember the fogged windows in the airport. Everybody wanted to sell you something: excursions, rupees, washing machines, fridges. We allow one man dressed in shiny shoes to convince us and manages to get us in his taxi. On the road with no hard shoulders, the traffic was heavy and the students ran around in their pristine uniforms between the tuk-tuks. Armed soldiers with Kalashnikov rifles kept watch under the coconut trees next to the fruit stalls and, inside the buses, people hanging off the doors. Nobody slowed down, everyone honk-honking each other. There were statuettes of giant saints in showcases, budhas, blue gods or trunked ones, houses about to collapse under the weight of colourful ads, skinny dogs, smoke and bikes, motorbikes, and traffic signs for decoration purposes only. They drive on the left. And on the right. And from the front. On the north of the island, the Civil war against the Tamil Tigers was still going on.

My jet lag slowed down the noise of landscapes seen for the first time. Colombo, the capital city, to the west, is the uggliest city anyone could visit; it stinks of vehicle fumes, of rotten rubbish and used oil, but we still ignored why Sri Lanka? We spinned around a world globe, stopped it and my index finger rested on Tissamaharama, the Yala National Park, the place where five years ago, in 2004, a tsunami swallowed the lives of two hundred and fifty people. Overall, over 30,000 lost their lives in an area also known as Ceylon, Serendib and Taprobane, and the Tear of India, and the island of one thousand names. We can see vast fields of crosses in their memory next to idyllic beaches.

But the big wave spared the Galle Face, as it still stands elegantly, ancient luxury, hardly a few meters off the Indian Ocean, separated by marina where children fly their kites. An orderly construction amidst chaos; or at least, an identifiable building. A resting place for your eyes, a stimulating location. The hotel was built in 1864. Since he began working there seventy-two years ago —as a bellman and then as an institution—, Kottarappu Chattu Kuttan was in charge of welcoming tourists, often British, as well as Princess Alexandra of Denmark, or Nixon, Gandhi, Arthur C. Clarke, a regular guest who finished in the hotel his last novel, 3001, final odyssey. Our suitcases were wheeled off marbled floors and Indian carpets into a lacquered wood lift that creaked as we ascended. The room was massive, and the patchouli could not disguise the smell of pipes and the seaside. The blades of the roof ventilator turned around lazily. At eight in the morning, the heat felt sticky.

I read they have renovated the classic wing in the hotel, finished by the architect Thomas Skinner in 1894, the original façade still intact. I read that Kottarappu Chattu Kuttan died a few months after the renovation. When we went to visit it, the classic wing still maintained its air of decadence of defiance against the passage of time, the beautiful charm of things that do not work anymore, as the lamps that did not work anymore. We could not care less. After some deep sleep, we came down for a meal. Sitting at the porch supported by pillars, we suddenly became explorers in a classic adventure movie or actors in a comic strip of Tintin. In fact, despite being set in Thailand, The Bridge over the river Kwai, directed by David Lean and based on Pierre Boulle’s book, was filmed in the forest of Sri Lanka, near Kitulgala.

We see the vast terrace shaped as a chess board facing the Ocean. We make out the remains of a wedding; flags fluttering and flower garlands swayed in the breeze as the sun heated up the empty chairs. This terrace bears witness to spectacular sunsets over the Indian Ocean and sometimes, people put their cocktail glasses down and applaud. The crows walk threateningly towards the porch, in small jumps, and when a German tries to bring his sandwich to his mouth, one of the crows snatches it from his hands with its claws and flies away. Someone targets it with a sling.

[dropcap letter=”K”]

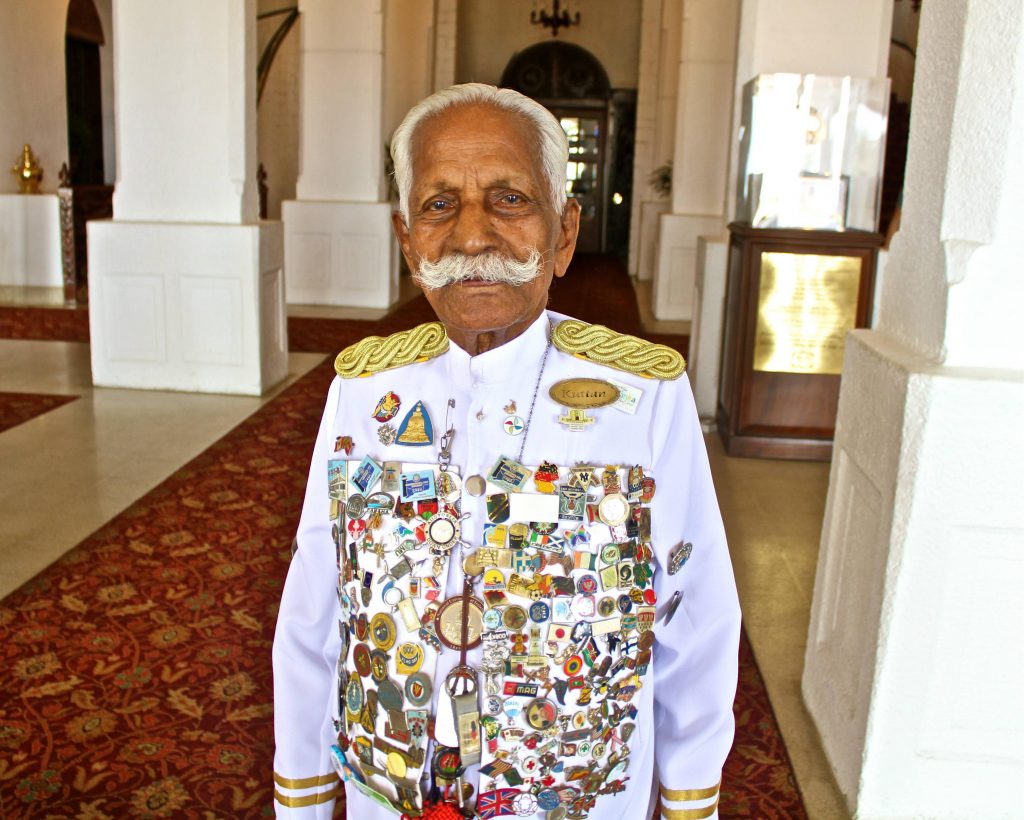

ottarappu Chattu Kuttan is dead. I do not recognize him by his name, but by a photo published in an English paper. Dressed in black, his chest decorated with badges and a bushy moustache, sunken eyes and aquiline nose, he was waiting at the staircase, his hands folded, for the guests of Hotel Galle Face, in Sri Lanka, the oldest colonial hotel in Asia. Galle Face is one of the thousand places one should visit before dying, according to a book and the website of our booking —which had conveniently erased with photoshop the horrible buildings showing up on the back.

I remember the fogged windows in the airport. Everybody wanted to sell you something: excursions, rupees, washing machines, fridges. We allow one man dressed in shiny shoes to convince us and manages to get us in his taxi. On the road with no hard shoulders, the traffic was heavy and the students ran around in their pristine uniforms between the tuk-tuks. Armed soldiers with Kalashnikov rifles kept watch under the coconut trees next to the fruit stalls and, inside the buses, people hanging off the doors. Nobody slowed down, everyone honk-honking each other. There were statuettes of giant saints in showcases, budhas, blue gods or trunked ones, houses about to collapse under the weight of colourful ads, skinny dogs, smoke and bikes, motorbikes, and traffic signs for decoration purposes only. They drive on the left. And on the right. And from the front. On the north of the island, the Civil war against the Tamil Tigers was still going on.

My jet lag slowed down the noise of landscapes seen for the first time. Colombo, the capital city, to the west, is the uggliest city anyone could visit; it stinks of vehicle fumes, of rotten rubbish and used oil, but we still ignored why Sri Lanka? We spinned around a world globe, stopped it and my index finger rested on Tissamaharama, the Yala National Park, the place where five years ago, in 2004, a tsunami swallowed the lives of two hundred and fifty people. Overall, over 30,000 lost their lives in an area also known as Ceylon, Serendib and Taprobane, and the Tear of India, and the island of one thousand names. We can see vast fields of crosses in their memory next to idyllic beaches.

But the big wave spared the Galle Face, as it still stands elegantly, ancient luxury, hardly a few meters off the Indian Ocean, separated by marina where children fly their kites. An orderly construction amidst chaos; or at least, an identifiable building. A resting place for your eyes, a stimulating location. The hotel was built in 1864. Since he began working there seventy-two years ago —as a bellman and then as an institution—, Kottarappu Chattu Kuttan was in charge of welcoming tourists, often British, as well as Princess Alexandra of Denmark, or Nixon, Gandhi, Arthur C. Clarke, a regular guest who finished in the hotel his last novel, 3001, final odyssey. Our suitcases were wheeled off marbled floors and Indian carpets into a lacquered wood lift that creaked as we ascended. The room was massive, and the patchouli could not disguise the smell of pipes and the seaside. The blades of the roof ventilator turned around lazily. At eight in the morning, the heat felt sticky.

I read they have renovated the classic wing in the hotel, finished by the architect Thomas Skinner in 1894, the original façade still intact. I read that Kottarappu Chattu Kuttan died a few months after the renovation. When we went to visit it, the classic wing still maintained its air of decadence of defiance against the passage of time, the beautiful charm of things that do not work anymore, as the lamps that did not work anymore. We could not care less. After some deep sleep, we came down for a meal. Sitting at the porch supported by pillars, we suddenly became explorers in a classic adventure movie or actors in a comic strip of Tintin. In fact, despite being set in Thailand, The Bridge over the river Kwai, directed by David Lean and based on Pierre Boulle’s book, was filmed in the forest of Sri Lanka, near Kitulgala.

We see the vast terrace shaped as a chess board facing the Ocean. We make out the remains of a wedding; flags fluttering and flower garlands swayed in the breeze as the sun heated up the empty chairs. This terrace bears witness to spectacular sunsets over the Indian Ocean and sometimes, people put their cocktail glasses down and applaud. The crows walk threateningly towards the porch, in small jumps, and when a German tries to bring his sandwich to his mouth, one of the crows snatches it from his hands with its claws and flies away. Someone targets it with a sling.