[dropcap letter=”T”]

hroughout 2018 several exhibitions have been programmed to commemorate the centenary of the death of Egon Schiele, victim of the so-called “Spanish flu”. A disease that a few days before took the life of his wife Edith, six months pregnant. Being only twenty-eight years old, Schiele left a huge amount of paintings, drawings and sketches, many of which were mis-sold, lost or even burned by the authorities, according to the sexual theme, predominant in his work, but far from being the only relevant. The threat of censorship, which his contemporary Karl Kraus had greeted as a way of stoking wit (by stating that any work that failed to avoid it was because, in fact, deserved to be censored), did not prevent Schiele from recreating himself in the artificial and explicit reproduction of bodies frequently naked, offered in arduous contortions.

EROS AND THANATOS: A DYONISIAN FEEDBACK

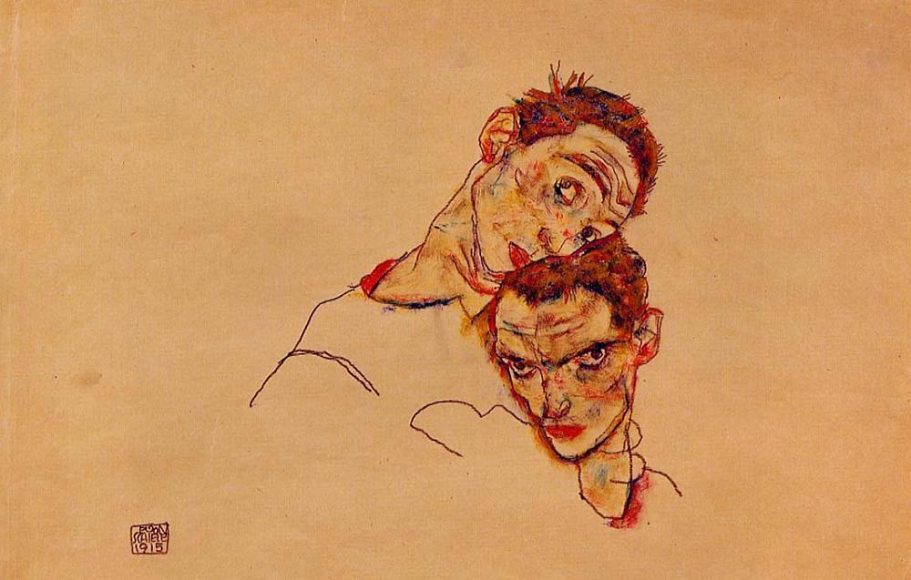

The themes chosen by Schiele were not classic ones, in which nudity was justified, nor did they benefit from the decorative graciosity of some of the painters of Viennese modernism -the Secession– who admired him, Gustav Klimt at the head. Schiele stood out as a portraitist because of his ability to transfer the psychological complexity of the person by means of simple lines in his drawings (or with a notorious brushstroke, of great expressiveness, in his paintings), connecting in an almost immediate way with the spectator, who nevertheless perceives it with amazement. Something especially striking in the hundreds of self-portraits he made, through a self-attention at times indiscriminately histrionic. The search for the self, as a specular recreation -which some have called narcissistic- runs parallel to the representation of the non-self, the other, which longs to be possessed, assimilated from the distance that the artist also identifies in himself. In his poem “A self-portrait” of 1910, he writes: “I am for myself and for those / to whom my intoxicating thirst / to be free gives everything, / and also for all, because all of them / I also love, I love”.

One of the most disconcerting aspects of Schiele’s production lies in the poses and even the grimaces of the figures represented, which exhibit their intimacy shamelessly and alien to any story that justifies their material disposition. The flesh of human beings is shown so naturally -free of make-up or cosmetic arrangements in its exhibition- that it falls to become pure materiality: a kind of still life in which the person has disappeared, either because he/she does not show his/her face or because his/her look is that of an absentee (puppet, automaton or body without life). The love that Schiele says he professes universally may seem incompatible with the conversion of the person who is reproduced into a “thing”. And, nevertheless, we recognize in his case an attempt -not an easy process, undoubtedly- of conciliation of the extremes. A discourse that, in a non-conceptual way, his works transmit to the viewer, displacing him/her from any assurance, and which may well be -according to David Foster Wallace’s expression in This is Water– “socially repulsive”. For we are also living beings, and we tolerate badly the reification by our neighbour, or as a reminder of the possibility that awaits the end, usually denied or replaced by beliefs (forms of knowledge) that provide handholds and, in short, tranquillity.

Schiele’s fate is announced and assumed in the famous Tod und Mädchen, a canvas in which he himself, characterized as death, embraces a young woman on her knees. It’s the farewell to his lover, before marrying Edith. Next to her, he will meet the deadly disease.

Being the mythical story or the realistic representation denied in Schiele, it seems that, in effect, there is no place for those sinister figures. Thus, more than mere eroticism, what they awaken, and reveal, is the other face of being, which does not wish to perpetuate life, or not only. The poem above cited Schiele closed with the verses: “I am a human being, I love / death and I love / life”. In his work, with a perfect and paradoxical coherence, a feedback between eros / thanatos -to use the terminology of the time- is explained in a way that does not leave the spectator indifferent. The cadaverous reality, the thing that one is manifestly when he/she stops being-alive, already appeared inserted in a more or less subtle way in many paintings of the Western tradition, under the topic of memento mori (“remember that you are going to die”). This is the case of The Ambassadors, by Holbein the Younger, in which a skull in anamorphosis -scarcely perceptible in the first instance, for the natural gaze- tears the canvas, distorted, insinuating the sinister reality that underlies every mundane enterprise, from beginning to its end.

In Schiele we find that apprehension on the negative side, but devoid of a moralizing tone. Wonderful the prose poem that called Forest of firs, in which he uses grammar with a strange and significant freedom, a poem that he closes with the sentence Alles ist lebend tot (“everything is alive dead”). This is neither juvenile rhetoric nor mere fatality, in the romantic sense, but a commitment to the Dionysian understanding of life, comparable to that claimed a few decades before by Friedrich Nietzsche (declared a follower of that Greek god, with whom the whole existence is celebrated, life and death, desire and suffering, creation and destruction …). Schiele’s fate is announced and assumed in the famous canvas Tod und Mädchen, in which he himself, characterized as death, embraces a young woman on her knees. It’s the farewell to his lover, before marrying Edith. Next to her he will meet the deadly disease.

As it happens in so many of his works, the characters seem to float, they lie “upon” the background, as if they were not already part of this world. The image, clearly figurative, nevertheless prefigures the desire for an extreme and liberated expression of the closed form, which abstract art will exploit. With the same title of that mythical painting, which undoubtedly refers to the composition of another Austrian who died at an early age, Franz Schubert (the quartet for strings known for the presence of the lied Das Tod und das Mädchen, completed in 1824), has recently made a film production focused on the work of Schiele. Although it dates from 2016, it is re-programmed in Barcelona, seeking to coincide with the centenary. A rather soft biopic, directed by Dieter Berner (shows a very nice photography, with some of the real scenes, the bohemian town of Český Krumlov, for example), which nevertheless lacks of the required intensity: the actor’s good boy face, often with an open smile on it, is incompatible with the complex psyche that many of his paintings reflect.

It has been pointed out that Schiele gladly assumed the role of misunderstood genius, with the intention, perhaps, to transcend his time, according to a counter-intuitive logic that had also remembered Friedrich Nietzsche (author with whom it is tempting and pertinent to build bridges): “Posthumous men -I, for example- are worse understood than the current ones, but better heard. Said with more rigor: they are never understood, and hence our authority”, writes Nietzsche in the aphoristic section of The Twilight of the Idols (1889). And Schiele, in a letter addressed to Dr. Oskar Reichel: “Sooner or later will emerge a faith in my paintings, writings and words, which I say few times but in the most concrete way possible. My paintings so far are probably just preambles, I do not know”.

“Sooner or later will emerge a faith in my paintings, writings and words, which I say few times but in the most concrete way possible. My paintings so far are probably just preambles”

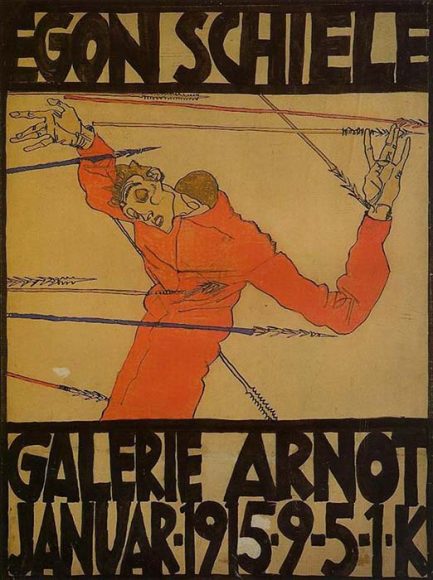

A almost religious confidence in his work, of an untimely nature -too premature for his time or, better, extemporal- is impregnated with an oracular taste, which suffers as a counterpart for the incomprehension of his contemporaries. Schiele came to be portrayed as a crucified Christ and as a arrow-wounded St. Sebastian, which in turn is comparable to the parody that Nietzsche performs with the parabolic and often caricatured Thus spoke Zarathustra, considered to be by him “the best gift that anyone has ever done to humanity “(despite the fact that, according to his Ecce homo, the biblical expression with which Christ was delivered to the authorities, no contemporary was capable of appreciating it). As for Schiele, he sent a painting that Klimt himself had commented in terms of praise to the same doctor, saying: “Surely it is, currently, the best that has been painted in Vienna. Whoever laughs at it must be observed for the way he laughs; He is an enemy of my art, envious of my art”.

All those complexities disappear in that movie, which neither illustrates Schiele’s fame of being an enfant terrible, nor scrutinizes the most tortured regions of his psyche, both in regard to the apprehension of an omnipresent death -which will affect his loved ones– or to the elusive reality of desire. The film eludes the most inexplicable issues, offensive to the morality in the context of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and also to the current, as we will see in the second part of the article, soon. The favourite subjects of Egon Schiele -we shall remember- are those that Sigmund Freud had considered primordial instincts: eros and thanatos, life instinct and death instinct are fed back eerily in the artist’s celebration. With a nervous and accurate sketch he delineates living-dead figures, bodies of beings that disconcert due to their beloved -and yet denied- reality.

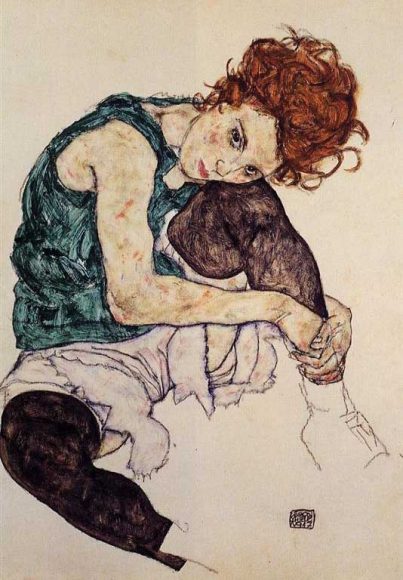

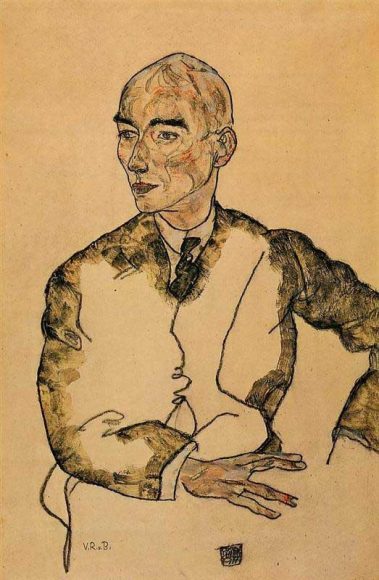

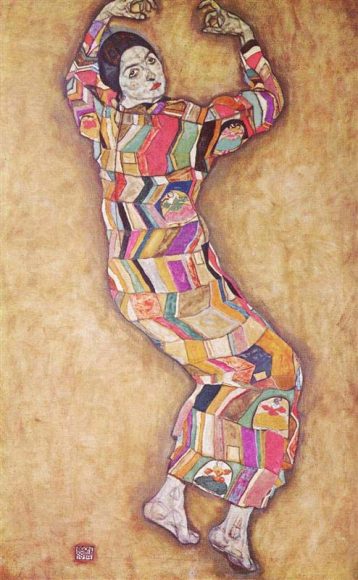

Featured images:

1. Seated Woman with Bent Knee, 1917

2. Death and the Maiden, 1915

3. Portrait of Dr. Viktor Ritter von Bauer, 1917

4. Double Self Portrait, 1915

5. Autumm Trees, 1911

6. Portrait of Friederike Maria Beer, 1914

7. Self Portrait as St. Sebastian (poster), 1914

8. Kniende mit hinunter gebeugtem Kopf, 1915