A tree in the city is much more than ornamentation...

The new Movistar Car service provides a Wi-Fi network in...

The audiovisual sector has a motto that will always prevail:...

Experiencing a match day in the Wanda Metropolitano Stadium allows...

Maybe because of tradition, or because of its huge media...

Who is primarily responsible for the so-called "greenhouse effect"? What...

Film, from the beginning a way to portray the unportrayable...

In Stuttgart there are two imposing museums for two leading...

The textile company that designs, manufactures and markets accessories for...

Animac, scheduled for the 22nd to 25th of February in...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”T”]

he space from where the writers build up their books ends up with more questions than answers: journalism and history travel in broad daylight, displaying all the details with a blinding impudence; narrative, on the other hand, hides truths —that are nothing but lies— under diluted contours in thick fog. This is a gothic and intriguing image, surely arguable. The city, as entertainment or as a daily suffering, is the arena of a large number of fictions. From the birth of modern novel, Barcelona has attracted the attention of hundreds of authors and, hence, has appeared in a remarkable number of iconic texts, from The Quixote to Private Life, Mariona Rebull, In Diamond Square, Last evenings with Theresa and The whole dimension of tragedy. His literary presence has become more and more relevant as years go by

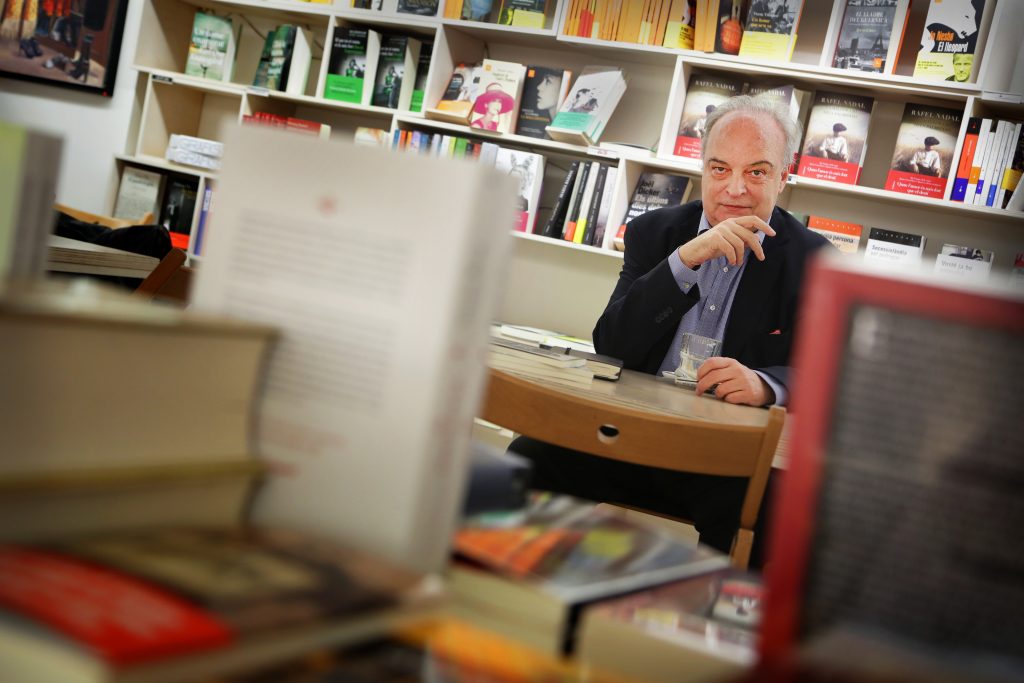

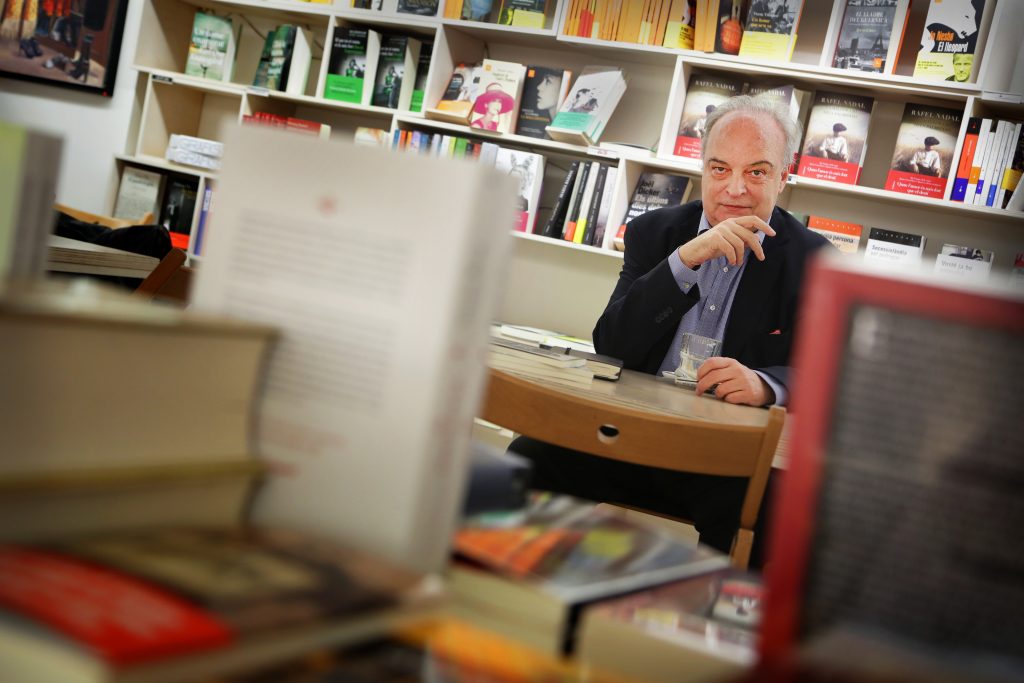

Enrique Vila-Matas’ novels are mostly set in urban spaces. “I write fiction from a space usually occupied by essay writers, from a position where I can plot, think or write under the avatar of a narrator —he says—. This narrator is always in Barcelona, which is where I have written 95% of my overall literary production. What happens in my books could well happen anywhere else, because it happens in my mind and, therefore, could even happen in Barcelona”. In his novel, The Illogic of Kassel (2014), his character takes his stay at a German contemporary art festival as a escape from his city. “It is true that I have always wanted to leave Barcelona —he admits—. I feel less alone and more comfortable and understood in Paris, New York, Mexico DF and Buenos Aires, to name just a few places where this is obvious. But I stay, because the best way of leaving is staying. The same applies to flies. Where are they safest? By the fly swatter”.

Vila-Matas has recently received the award of the Book Fair of Guadalajara, enjoys an internationally undeniable prestige and could well receive the Nobel Prize of Literature. He can easily be found at the +Bernat bookshop in Carrer Buenos Aires, nearly always in the company of his wife, Paula de Parma, who he dedicates all his books to. This is precisely one of the settings for his novel Dylan’s Air (2012). When he is not there —or travelling— he writes from home. “I work from the same block of flats where José Mallorquí wrote the El coyote, a bestselling series of popular novels during the Spanish postwar”, he remembers.

Novels and cities

For a long time, one of the recurrent debates in the Catalan capital city was finding the novel that had best portrayed Barcelona, although, often, their conclusions contained political undertones and even commercial excuses. Sergi Pàmies joked about this in The great novel about Barcelona (1999), one of the book within a series of fifteen short stories of 144 pages, altogether. “I find this an inexistent debate that did not exist either back then —he states—. From time to time, somebody regretted the absence of a novel about Barcelona. On the reasons for the absence of this debate, the theories are manifold, but I tend to think that there is no such debate because, both in Spanish and in Catalan, there is a large number of novels and novelists who have literarily explained the city in such a dignified way that there is no reason to insist on this tedious issue”.

Pàmies was born in Paris in 1960 and lived in Gennevilliers —in metropolitan Paris— until he was eleven. He published his first collection of short stories in 1986, I shall fall heads on shame, with predominance of unlocalized urban spaces, in common with his other three novels, published between 1990 and 1995, edited by Jaume Vallcorba Plana. “I was under the impression that, without name, biography and without a specific location, stories could deliver a sense of helpless inclemency —he acknowledges—. Later on, I realized that the effort to hide identifying details worked against the story and stopped doing it, depending on its usefulness or uselessness”. This new narrative strategy is revealed in such books as The Exercise Bike (2010) and Love Songs (2013), published in the same year as All those things that died one afternoon with the bicycles, by Llucia Ramis. “The protagonist has to go back to her parents’ house because she has lost her job and has no money —recalls the writer and journalist about unwanted and forced changes of scenario: she has to leave Barcelona and settle temporarily in Palma de Mallorca—. The bubble on which she carefully treaded on suddenly burst, and is now going free fall. She also realizes that, because of this caution, she has not built anything, everything has been temporary for too long and has never had a project for the future”. Llucia Ramis, apart from writing from her bedroom, has done so from “bar terraces in Gràcia and La Sagrera”, and some time ago, had worked as a hostess for a while, and she had written on notebooks from the bar behind the Catalan local television TV3.

The grande ‘madame’ of the bubble

Llucia Ramis arrived in Barcelona at the end of the 1990s and the city has become one more character of her narrative. She recalls the atmosphere she encountered when she arrived: “She was a madamme who prostituted us all. She had undergone so much aesthetic surgery to look beautiful that she started looking like the others, with all that botox in her face and silicone implants in her tits. She was vulgar; she displayed the same shops and looks of every high street in any city in the western world. She was forever at a surgery room, his bowels always facing up, and the cranes and the drills constituted a promise that would never come true. There were construction works everywhere. She sold herself to anyone, from builders to tourists, and we, its citizens, could do nothing but lowering our heads and sell ourselves to her. She was expensive to Barcelona citizens, and sold herself cheap to the rest”.

A darker and more criminal atmosphere than that of Llucia Ramis appears in Street of the Forgotten, by Stefanie Kremser, published in German in 2011 and translated into Catalan and Spanish one year later. “I speak about a Barcelona shaken by speculation, property mobbing, touristic boom and the massive construction of hotels in Ciutat Vella… This is a Barcelona with an old town about to become a picturesque but empty backdrop, empty of local life, empty of space for its people”, she explains. The assassin of this novel is a disturbed person who wants to put an end to gentrification. Kremser was born in Germany in 1967, but grew up in São Paulo. She settled in Barcelona a Little more than a decade ago, during which time she has published crime novels set in this city like The bad woman, by Marc Pastor (2008), of I was Johnny Thunders, by Carlos Zanón (2014). She has written books with this backdrop like Der Tag, an dem ich fliegen lernte —in process of Catalan translation— and scripts for the tv series Tatort: 90-minute chapters of open-closed stories, revolving around a murder. “As a port city, Barcelona has a specific trait of being a city of arrival —says Kremser—. When I walk around Raval I imagine it is similar to New York one hundred years ago, or São Paulo in the 60s. These cities have centennial traditions as melting pots. Despite its relatively small size, one of its gifts is being tolerant, and has the ability of living with many languages, with several foreign heritages and associated beliefs. And despite its radical social contrasts. Barcelona does not claim complete assimilation or absolute homogeneity because it has wisely learnt that such things do not exist”. Apart from reporting the property bubble in The Street of the Forgotten, Kremser misses “the recognition of intellectual and artistic professions”. She adds: “If respect and support for cultural creativity were not lagging behind, this could be a great city for writers and artists of all types. We have many sources of inspiration but we cannot live on beautiful air”.

Two writers in the library

Job insecurity in the world of culture is the main topic behind Albert Serra (the novel, not the namesake cinema director), the first novel written by Albert Forns, published in 2012. “I portray Barcelona nowadays, specially my day to day experience, always trying to retrieve the strange view, surprise, the alien viewpoint of someone who sees something for the first time, with a view to avoiding grey and mechanical descriptions”, he says. Forns is from Granollers, but has been living in the area of Gràcia for some years now. Albert Forns has built Albert Serra and his own book from libraries, estate-owned and private. “I am a staunch believer in documentation and reading while writing, as I want one idea to lead me to the next one. In this respect, libraries are an endless source of books —he claims—. They are also quiet places, especially in the mornings when there are no children around, they’re comfortable (nice and warm) and free of noise and people, I would have to pay so much if I worked from a coffee bar”. Forns speaks highly of libraries that request accreditation, like that in the Ateneu —in the past, a place frequently visited by Josep Pla and one where Sagarra wrote for two summer months Private Life—, that in MACBA or in Fundació Tàpies: “You can leave your laptop on the table, ask the person in front of you to keep an eye on it, go down for lunch or having a leisure coffee break. You have all the comfort of an office without having to pay for coworking”. Apart from peacefulness, safety and economic advantages of working from a library, Forns also treasures the fact that you have no distractions or obligations to do the dishes or the laundry: “At home you have all types of excuses to stop writing”.

Also, Ignacio Vidal-Folch, author of an extended, robust and surprising narrative work, usually works from libraries. “I like the Biblioteca de Catalunya because of its gothic naves, so airy and relativizing of our daily lives and, of course, because I can look up books I don’t have at home —he points out—. The library in MNAC is very white and has natural light. As it stands slightly apart from the museum, it is usually empty, which is nice. Shame that in both of them, like many other libraries throughout Spain, the timetables fall short of the needs. On Saturdays afternoon they are closed, like Sundays”.

It was in the Biblioteca de Catalunya where Eugeni d’Ors managed to create, during the second decade of the 20th century, when he was the General Secretary of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Vidal-Folch has worked on some of his novels such as Contramundo (2006) or We will soon be happy (2014) and the essays Barcelona, secret museum (2009): “The recurrent passing on the same locations can turn a beautiful city into a routine, almost invisible, setting; in Barcelona, secret museum I intended to highlight, thanks to my cultural memory and that of some of my friends who told me about their ideas, a fluent relationship between urban places and those of paintings, literature and cinema in an attempt to inject new life and new mysteries in an old setting”.

Vidal-Folch started publishing comic strips in Barcelona in the early 80s, the same Barcelona as that of detective Pepe Carvalho, created by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán a few years back, when he was hatching The City of Prodigies, by Eduardo Mendoza published in 1986, also the inspiration of Juan Marsé in The bilingual lover (1990) and the setting of numerous stories and articles by Quim Monzó. What has changed, between that city and the contemporary one? “The main difference is that in that early Barcelona I was young and now, I am not —he replies—. The change of viewpoint changes the event completely. Maybe because of this, the city from before the ‘damned Olympic Games’ is rusty, run-down and cramped but more vital and hopeful, with more open perspectives. In general, the entire world is ugglier from one decade to the next. Just like me”.

A place to stay or to escape from?

Imma Monsó lived in Barcelona from ages 17 to 32: “When I was little, I dreamt about living there, but after three years living there, I want to leave —she recalls—. I discovered that what I like most is having it very close to me, arriving there and leaving”. Before her debut with You never know (1996), Monsó had been living in Sant Cugat for a while. “From my place, I can see the Tibidabo and I like to think that the city is behind it, full of expectations and life but at a distance. What I like most about it is driving from the road of Arrabassada and seeing its formidable panoramic view, but any other entrance road is fine by me. Same thing with the exit roads: Barcelona, to me, has never meant a safe home but adventure”. The city appears “sketchily” in the novels of this award-winning author of the Ramon Llull award in 2012 and the National Award of Literature with The fast woman: “Fields and forests are essential settings in my fiction”, she acknowledges.

Bel Olid made her debut in 2011 with A solitary land, but it was a year later, when she published The bad reputation that she consolidated as an author with a literary voice, disturbing and uncomfortable. Some of her best stories in the book are set in Barcelona, adding her name to that of a heterogeneous tradition of previous narrators, from Pere Calders, Mercè Rodoreda and Jordi Sarsanedas to Pedro Zarraluki, Francesc Serés, Maria Barbal and Marta Rojals. “In general, I am interested in the city as a place where the implausible becomes possible, as a space that admits deviation from the norm, more easily than in the countryside, a place where social control is stronger —she claims—. The city is also a place of shared solitude, of course”. Olid finds it difficult to write from home and has her own “mental map in quiet bars and wifi access” and often works from there: “You feel as if you were at an airport or in a hotel, all the time waiting for the next plane is yours, nobody interrupts you, and you can write without feeling remorse of not doing something useful”.

Isolation in a bar does not estimulate the creativity of Lluís-Anton Baulenas. Whenever he documents himself for one of his novels —where, he admits “the appearance of Barcelona is a constant feature”— he goes out with a camera. “Later on, at home —he adds— I retrieve the information I was looking for thanks to the image”. In Happiness (2001), I recreated the transformation of a city in the early 20th century, and in When the madman comes and takes me away ( 2013) was set in Raval during the years of the last crisis, in the streets that serves as the backdrop of the “outraged” and highly recommended The deserter in the battle field, by Julià de Jòdar, and Carrer Robadors, by Mathias Énard, published in the same year as Baulenas’ novel. “Both in contemporary novels and those set in the past —he says— I give an image of an ancient city, with lots of layers of accumulated experience, capable of everything, the best and the worst”. Two spaces that appear from time to time in his novels are service areas and petrol stations: “The anecdotes pivoting around these locations are the result of observation —he says—. I have written about an employee in a petrol station store reading a book about philosophy or about a petrol station in a highway chosen as the exchange location of the son of a separated couple, as the middle point between their two homes”.

The truck drivers in Lost suitcases, by Jordi Puntí, could have refuelled in some of the Barcelona petrol stations of Baulenas’ novels. Since it was first published in 2010, the novel has been translated into 15 languages: its success abroad has few precedents in Catalan literature, and started one year before with I confess, by Jaume Cabré, with Barcelona as the outstanding backdrop. “Both in short stories like Armadillo skin (1998) and Sad animals (2002) the city is a veiled presence, described often with plenty of detail because it helps define the characters, but instead appears without a name because I am interested in blending it with other cities, especially European ones: places where design has succeeded, where all the shops look the same, where couples argue in the Ikea on the outskirts. In Lost suitcases, on the other hand, Barcelona is important and set it against a love story. The city helps me criss-cross the fate of the characters in my novel, get lost in it and cross their paths several times; in this process, the reader can revisit a time and understands the changes undergone by the city [back to the 70s], with the arrival of working immigrants and the growth of the suburban areas, for example, or the transformation of the former Camp de la Bota”.

Puntí has lived in New York most of this year, where he looked into the life of musician and orchestra conductor Xavier Cugat, the protagonist of his coming novel. Despite spending most of his life in the United States, in the 70s —while Rodoreda worked on her A Broken Mirror—, Cugat lived in Catalonia and stayed for a long time in one of the Ritz’ suites. “I can imagine Cugat living there back then, with a leisurely lifelong cultivated nonchalance, perhaps missing the days when he reigned over the Waldorf Astoria in New York”, says the author in one of the historical halls of the current Palace Hotel in Gran Via. In Puntí’s next novel, Barcelona will have a secondary role, but even so the city will shine on like a candelabra in a luxury hotel.

[dropcap letter=”T”]

he space from where the writers build up their books ends up with more questions than answers: journalism and history travel in broad daylight, displaying all the details with a blinding impudence; narrative, on the other hand, hides truths —that are nothing but lies— under diluted contours in thick fog. This is a gothic and intriguing image, surely arguable. The city, as entertainment or as a daily suffering, is the arena of a large number of fictions. From the birth of modern novel, Barcelona has attracted the attention of hundreds of authors and, hence, has appeared in a remarkable number of iconic texts, from The Quixote to Private Life, Mariona Rebull, In Diamond Square, Last evenings with Theresa and The whole dimension of tragedy. His literary presence has become more and more relevant as years go by

Enrique Vila-Matas’ novels are mostly set in urban spaces. “I write fiction from a space usually occupied by essay writers, from a position where I can plot, think or write under the avatar of a narrator —he says—. This narrator is always in Barcelona, which is where I have written 95% of my overall literary production. What happens in my books could well happen anywhere else, because it happens in my mind and, therefore, could even happen in Barcelona”. In his novel, The Illogic of Kassel (2014), his character takes his stay at a German contemporary art festival as a escape from his city. “It is true that I have always wanted to leave Barcelona —he admits—. I feel less alone and more comfortable and understood in Paris, New York, Mexico DF and Buenos Aires, to name just a few places where this is obvious. But I stay, because the best way of leaving is staying. The same applies to flies. Where are they safest? By the fly swatter”.

Vila-Matas has recently received the award of the Book Fair of Guadalajara, enjoys an internationally undeniable prestige and could well receive the Nobel Prize of Literature. He can easily be found at the +Bernat bookshop in Carrer Buenos Aires, nearly always in the company of his wife, Paula de Parma, who he dedicates all his books to. This is precisely one of the settings for his novel Dylan’s Air (2012). When he is not there —or travelling— he writes from home. “I work from the same block of flats where José Mallorquí wrote the El coyote, a bestselling series of popular novels during the Spanish postwar”, he remembers.

Novels and cities

For a long time, one of the recurrent debates in the Catalan capital city was finding the novel that had best portrayed Barcelona, although, often, their conclusions contained political undertones and even commercial excuses. Sergi Pàmies joked about this in The great novel about Barcelona (1999), one of the book within a series of fifteen short stories of 144 pages, altogether. “I find this an inexistent debate that did not exist either back then —he states—. From time to time, somebody regretted the absence of a novel about Barcelona. On the reasons for the absence of this debate, the theories are manifold, but I tend to think that there is no such debate because, both in Spanish and in Catalan, there is a large number of novels and novelists who have literarily explained the city in such a dignified way that there is no reason to insist on this tedious issue”.

Pàmies was born in Paris in 1960 and lived in Gennevilliers —in metropolitan Paris— until he was eleven. He published his first collection of short stories in 1986, I shall fall heads on shame, with predominance of unlocalized urban spaces, in common with his other three novels, published between 1990 and 1995, edited by Jaume Vallcorba Plana. “I was under the impression that, without name, biography and without a specific location, stories could deliver a sense of helpless inclemency —he acknowledges—. Later on, I realized that the effort to hide identifying details worked against the story and stopped doing it, depending on its usefulness or uselessness”. This new narrative strategy is revealed in such books as The Exercise Bike (2010) and Love Songs (2013), published in the same year as All those things that died one afternoon with the bicycles, by Llucia Ramis. “The protagonist has to go back to her parents’ house because she has lost her job and has no money —recalls the writer and journalist about unwanted and forced changes of scenario: she has to leave Barcelona and settle temporarily in Palma de Mallorca—. The bubble on which she carefully treaded on suddenly burst, and is now going free fall. She also realizes that, because of this caution, she has not built anything, everything has been temporary for too long and has never had a project for the future”. Llucia Ramis, apart from writing from her bedroom, has done so from “bar terraces in Gràcia and La Sagrera”, and some time ago, had worked as a hostess for a while, and she had written on notebooks from the bar behind the Catalan local television TV3.

The grande ‘madame’ of the bubble

Llucia Ramis arrived in Barcelona at the end of the 1990s and the city has become one more character of her narrative. She recalls the atmosphere she encountered when she arrived: “She was a madamme who prostituted us all. She had undergone so much aesthetic surgery to look beautiful that she started looking like the others, with all that botox in her face and silicone implants in her tits. She was vulgar; she displayed the same shops and looks of every high street in any city in the western world. She was forever at a surgery room, his bowels always facing up, and the cranes and the drills constituted a promise that would never come true. There were construction works everywhere. She sold herself to anyone, from builders to tourists, and we, its citizens, could do nothing but lowering our heads and sell ourselves to her. She was expensive to Barcelona citizens, and sold herself cheap to the rest”.

A darker and more criminal atmosphere than that of Llucia Ramis appears in Street of the Forgotten, by Stefanie Kremser, published in German in 2011 and translated into Catalan and Spanish one year later. “I speak about a Barcelona shaken by speculation, property mobbing, touristic boom and the massive construction of hotels in Ciutat Vella… This is a Barcelona with an old town about to become a picturesque but empty backdrop, empty of local life, empty of space for its people”, she explains. The assassin of this novel is a disturbed person who wants to put an end to gentrification. Kremser was born in Germany in 1967, but grew up in São Paulo. She settled in Barcelona a Little more than a decade ago, during which time she has published crime novels set in this city like The bad woman, by Marc Pastor (2008), of I was Johnny Thunders, by Carlos Zanón (2014). She has written books with this backdrop like Der Tag, an dem ich fliegen lernte —in process of Catalan translation— and scripts for the tv series Tatort: 90-minute chapters of open-closed stories, revolving around a murder. “As a port city, Barcelona has a specific trait of being a city of arrival —says Kremser—. When I walk around Raval I imagine it is similar to New York one hundred years ago, or São Paulo in the 60s. These cities have centennial traditions as melting pots. Despite its relatively small size, one of its gifts is being tolerant, and has the ability of living with many languages, with several foreign heritages and associated beliefs. And despite its radical social contrasts. Barcelona does not claim complete assimilation or absolute homogeneity because it has wisely learnt that such things do not exist”. Apart from reporting the property bubble in The Street of the Forgotten, Kremser misses “the recognition of intellectual and artistic professions”. She adds: “If respect and support for cultural creativity were not lagging behind, this could be a great city for writers and artists of all types. We have many sources of inspiration but we cannot live on beautiful air”.

Two writers in the library

Job insecurity in the world of culture is the main topic behind Albert Serra (the novel, not the namesake cinema director), the first novel written by Albert Forns, published in 2012. “I portray Barcelona nowadays, specially my day to day experience, always trying to retrieve the strange view, surprise, the alien viewpoint of someone who sees something for the first time, with a view to avoiding grey and mechanical descriptions”, he says. Forns is from Granollers, but has been living in the area of Gràcia for some years now. Albert Forns has built Albert Serra and his own book from libraries, estate-owned and private. “I am a staunch believer in documentation and reading while writing, as I want one idea to lead me to the next one. In this respect, libraries are an endless source of books —he claims—. They are also quiet places, especially in the mornings when there are no children around, they’re comfortable (nice and warm) and free of noise and people, I would have to pay so much if I worked from a coffee bar”. Forns speaks highly of libraries that request accreditation, like that in the Ateneu —in the past, a place frequently visited by Josep Pla and one where Sagarra wrote for two summer months Private Life—, that in MACBA or in Fundació Tàpies: “You can leave your laptop on the table, ask the person in front of you to keep an eye on it, go down for lunch or having a leisure coffee break. You have all the comfort of an office without having to pay for coworking”. Apart from peacefulness, safety and economic advantages of working from a library, Forns also treasures the fact that you have no distractions or obligations to do the dishes or the laundry: “At home you have all types of excuses to stop writing”.

Also, Ignacio Vidal-Folch, author of an extended, robust and surprising narrative work, usually works from libraries. “I like the Biblioteca de Catalunya because of its gothic naves, so airy and relativizing of our daily lives and, of course, because I can look up books I don’t have at home —he points out—. The library in MNAC is very white and has natural light. As it stands slightly apart from the museum, it is usually empty, which is nice. Shame that in both of them, like many other libraries throughout Spain, the timetables fall short of the needs. On Saturdays afternoon they are closed, like Sundays”.

It was in the Biblioteca de Catalunya where Eugeni d’Ors managed to create, during the second decade of the 20th century, when he was the General Secretary of the Institut d’Estudis Catalans, Vidal-Folch has worked on some of his novels such as Contramundo (2006) or We will soon be happy (2014) and the essays Barcelona, secret museum (2009): “The recurrent passing on the same locations can turn a beautiful city into a routine, almost invisible, setting; in Barcelona, secret museum I intended to highlight, thanks to my cultural memory and that of some of my friends who told me about their ideas, a fluent relationship between urban places and those of paintings, literature and cinema in an attempt to inject new life and new mysteries in an old setting”.

Vidal-Folch started publishing comic strips in Barcelona in the early 80s, the same Barcelona as that of detective Pepe Carvalho, created by Manuel Vázquez Montalbán a few years back, when he was hatching The City of Prodigies, by Eduardo Mendoza published in 1986, also the inspiration of Juan Marsé in The bilingual lover (1990) and the setting of numerous stories and articles by Quim Monzó. What has changed, between that city and the contemporary one? “The main difference is that in that early Barcelona I was young and now, I am not —he replies—. The change of viewpoint changes the event completely. Maybe because of this, the city from before the ‘damned Olympic Games’ is rusty, run-down and cramped but more vital and hopeful, with more open perspectives. In general, the entire world is ugglier from one decade to the next. Just like me”.

A place to stay or to escape from?

Imma Monsó lived in Barcelona from ages 17 to 32: “When I was little, I dreamt about living there, but after three years living there, I want to leave —she recalls—. I discovered that what I like most is having it very close to me, arriving there and leaving”. Before her debut with You never know (1996), Monsó had been living in Sant Cugat for a while. “From my place, I can see the Tibidabo and I like to think that the city is behind it, full of expectations and life but at a distance. What I like most about it is driving from the road of Arrabassada and seeing its formidable panoramic view, but any other entrance road is fine by me. Same thing with the exit roads: Barcelona, to me, has never meant a safe home but adventure”. The city appears “sketchily” in the novels of this award-winning author of the Ramon Llull award in 2012 and the National Award of Literature with The fast woman: “Fields and forests are essential settings in my fiction”, she acknowledges.

Bel Olid made her debut in 2011 with A solitary land, but it was a year later, when she published The bad reputation that she consolidated as an author with a literary voice, disturbing and uncomfortable. Some of her best stories in the book are set in Barcelona, adding her name to that of a heterogeneous tradition of previous narrators, from Pere Calders, Mercè Rodoreda and Jordi Sarsanedas to Pedro Zarraluki, Francesc Serés, Maria Barbal and Marta Rojals. “In general, I am interested in the city as a place where the implausible becomes possible, as a space that admits deviation from the norm, more easily than in the countryside, a place where social control is stronger —she claims—. The city is also a place of shared solitude, of course”. Olid finds it difficult to write from home and has her own “mental map in quiet bars and wifi access” and often works from there: “You feel as if you were at an airport or in a hotel, all the time waiting for the next plane is yours, nobody interrupts you, and you can write without feeling remorse of not doing something useful”.

Isolation in a bar does not estimulate the creativity of Lluís-Anton Baulenas. Whenever he documents himself for one of his novels —where, he admits “the appearance of Barcelona is a constant feature”— he goes out with a camera. “Later on, at home —he adds— I retrieve the information I was looking for thanks to the image”. In Happiness (2001), I recreated the transformation of a city in the early 20th century, and in When the madman comes and takes me away ( 2013) was set in Raval during the years of the last crisis, in the streets that serves as the backdrop of the “outraged” and highly recommended The deserter in the battle field, by Julià de Jòdar, and Carrer Robadors, by Mathias Énard, published in the same year as Baulenas’ novel. “Both in contemporary novels and those set in the past —he says— I give an image of an ancient city, with lots of layers of accumulated experience, capable of everything, the best and the worst”. Two spaces that appear from time to time in his novels are service areas and petrol stations: “The anecdotes pivoting around these locations are the result of observation —he says—. I have written about an employee in a petrol station store reading a book about philosophy or about a petrol station in a highway chosen as the exchange location of the son of a separated couple, as the middle point between their two homes”.

The truck drivers in Lost suitcases, by Jordi Puntí, could have refuelled in some of the Barcelona petrol stations of Baulenas’ novels. Since it was first published in 2010, the novel has been translated into 15 languages: its success abroad has few precedents in Catalan literature, and started one year before with I confess, by Jaume Cabré, with Barcelona as the outstanding backdrop. “Both in short stories like Armadillo skin (1998) and Sad animals (2002) the city is a veiled presence, described often with plenty of detail because it helps define the characters, but instead appears without a name because I am interested in blending it with other cities, especially European ones: places where design has succeeded, where all the shops look the same, where couples argue in the Ikea on the outskirts. In Lost suitcases, on the other hand, Barcelona is important and set it against a love story. The city helps me criss-cross the fate of the characters in my novel, get lost in it and cross their paths several times; in this process, the reader can revisit a time and understands the changes undergone by the city [back to the 70s], with the arrival of working immigrants and the growth of the suburban areas, for example, or the transformation of the former Camp de la Bota”.

Puntí has lived in New York most of this year, where he looked into the life of musician and orchestra conductor Xavier Cugat, the protagonist of his coming novel. Despite spending most of his life in the United States, in the 70s —while Rodoreda worked on her A Broken Mirror—, Cugat lived in Catalonia and stayed for a long time in one of the Ritz’ suites. “I can imagine Cugat living there back then, with a leisurely lifelong cultivated nonchalance, perhaps missing the days when he reigned over the Waldorf Astoria in New York”, says the author in one of the historical halls of the current Palace Hotel in Gran Via. In Puntí’s next novel, Barcelona will have a secondary role, but even so the city will shine on like a candelabra in a luxury hotel.