The audiovisual sector has a motto that will always prevail:...

There are things that only happen once in a lifetime....

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

Producing and marketing homes within demand-based pricing will continue to...

A good friend is with you to the end of...

Alzheimer's is, like the human brain itself, a mystery to...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

Hollywood has taught that three possible destinations await humanity: fighting,...

Take a deep breath. Alright? We are going to talk...

In critical times, it is fair to determine the relevance...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

The City is concealed behind its best fog, the bells inside the Big Ben remain silent and the cranes over the river Thames bowed in respect at the passage of the entourage of the funeral for Winston Churchill. It was on 31st January 1965, and that was a grand occasion. London —as chroniclers report— had never seen anything like this since the time of Gladstone as a Prime Minister. Nor would they see it again: the solemn funeral for this great statesman would be the last one displaying “the British tradition of imperial ceremony”. The arrangements for the funeral had been carefully set out by Elizabeth II: slow liturgy, restrained grief, subdued pomp and the final glorified moment of gun salutes. A true state funeral.

From Saint Paul’s cathedral to Blenheim, this reverence spread across the many English citizens who took the streets to witness the procession. As the coffin proceeded, the bobbies touched their helmet to salute; the civilians took their hats off. Their sorrow was tearless sadness, no unnecessary sobbing, no signs. These were the same old British people described by Orwell, in football stands, as gentle and quiet going to Sunday mass service. On that particular day they were the embodiment of a grateful nation. Many years after that glorious afternoon, one might think that could be an exaggerated propaganda farewell ceremony —as one oblivious historian said— to “that funnily dressed man who drinks wine for breakfast”. Still, those secretaries from the War Office and those East End shop assistants did not have to wonder why they were there. They knew how much they owed this man. Surely, some of them had fought at the other side of the Channel. Many had lived, in the same streets, the Blitz, the “terror bombing”. And they all had found a reason for courage and hope in the voice that, through the BBC, knew how to shout out “we shall never surrender”. In that critical hour of 1940, as Ian Buruma reports, the world had no other handhold than Winston Churchill’s moral vigour. A merciful tribute to his memory was the least they could do.

On facing England’s battle, Store reports, “a leader of sober judgement could have well concluded that there was no hope whatsoever”. Luckily, of all the adjectives describing Winston Churchill, being “sober” is the least frequented of them all. He would always sleep randomly, and his eating habits defied schedule. While labour leader Attlee handled much of the organisational work, Churchill entertained his Chief of the Imperial General Staff until dawn, soaking in scotch and alcoholic loquaciousness. He would smoke between nine and ten cigars a day, had a confessed weakness for vintage brandy and —according to his own estimate— uncorked forty thousand champagne bottles. But perhaps a statesman needs certain virtues in times of peace and others in times of war. Churchill never had a sense of proportion, temperance or moderation. However, leadership was in his blood, the son of an old Marlborough trunk. From his father, he inherited his poise of an Englishman seasoned in Victorian certainties; from his mother, individualist optimism of the Americans of the best age.

He would smoke between nine and ten cigars a day, had a confessed weakness for vintage brandy and —according to his own estimate— uncorked forty thousand champagne bottles

That’s the origin of the noblesse oblige of the aristocrat, ensued by the political gift of opportunity, the foresight of the military and the instinct of a historian. Yet one more trait of character can be accredited to his lineage: a blend between audacity and recklessness probably dating back to a genetic origin between Raleigh and Drake, which would distinguish him from contemporary politicians.

On studying the Churchillian temperament, lord Owen, therefore, hits the nail on the head about his caveat: when talking about Winston Churchill, nobody should think about him about a standard person. His enemies, e.g. Hitler, were by no means standard, either. Nor was his life standard, a life that saw the last cavalry charge and the initial steps of the space race, the rise and fall of the British Empire, the discredit and the popularity and —in his own words— “triumph and disaster”. From both ends, he emerged victorious in the Second World War, held innumerable high-profile positions, set standards as a historian, was awarded the Nobel Prize of Literature and gave name to hallmark Cuban cigar and polka-dot bow ties. For any man, fighting in the three continents or enjoying journalistic celebrity would have meant a vital achievement: in Churchill’s biography, these rank as minor glories.

Many have tried to assess Churchillian grandeur. Phyllis Moir, one of Churchill’s secretaries, was insistently asked about this. The good old woman devoted years to come up with an answer. In the end, she wrote that “it was impossible to work with Mr. Churchill for some time without having the feeling that he was a predestined man”. It is difficult to read things like that in writings by political scientists. But when Moir portrays Churchill as someone working non-stop and rushing all the time, one can’t help thinking that he was someone urgently trying to accomplish his fate.

His haste was soon revealed. On his admittance to Sandhurst’s Military Academy, young Churchill wrote a letter to his mother expressing his solemn intention to “do something in this world”. The time of the shy child was left behind, as well as the poorly disciplined and unpopular student in Harrow, one of the race’s nurseries. “Doing something in this world”: the same phrase had previously been used by Benjamin Disraeli. Like the eminent Victorian, Churchill would step up the pace to accomplish that end: he may not have a great intellectual background, but what he did have was a magnificent Hussar uniform to honour.

He also had a fearless bravery to the point that one should wonder what would have become of Winston Churchill should he have saved his energy striving for war, instead. His historical background never ceases to astound us. Before turning twenty-five, he had participated in fifty operations with live ammunition in Cuba, India, Sudan, Egypt and South Africa. And he did so, virtually always, by adopting a two-pronged profile, as a soldier and as a journalist, halfway between “making ends meet” and poorly meditated romanticism. Sometimes —like during the Boers war— he was only working as a journalist, but even then managed to get in trouble. For example, in South Africa his train suffered an attack, and Churchill took control of the situation and never received any Victoria Cross (VC), if only as a civilian. Later on, confined in Pretoria, he added more pages onto his heroic young achievements: his escape from a prisoner camp and landing in Lourenço Marques —Mozambique’s capital city, separated by no less than three hundred miles— was received in England as the adventures of a Lord Byron of sorts. With hindsight, these were only the budding stanzas of an epic drama.

No Churchill, the statesman, would have ever existed, without the existence of a previous Churchill, the soldier. Therefore, Churchill’s return to the military life should not come as a surprise: after his early and frustrated adventure in Oldham, in the late 19th century, came his participation in the Great War, at breakneck speed, as a sign of atonement after his military debacle in Gallipoli. But South Africa had been his revelation to the world and, the resulting popularity projected him to politics: by the wake of the new century Churchill had become an MP. Shortly before, he had turned to his mother: “I telegraphed her and asked her to send me books”. It was this pragmatism that shaped the prose of a historian on Gibbon’s lined sheets and —according to Bernard Shaw— the greatest stylist of England of his time.

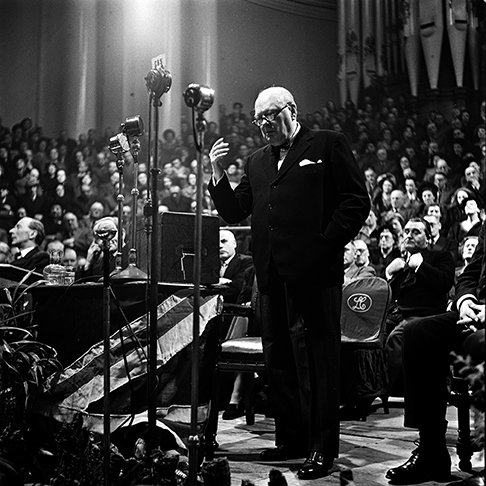

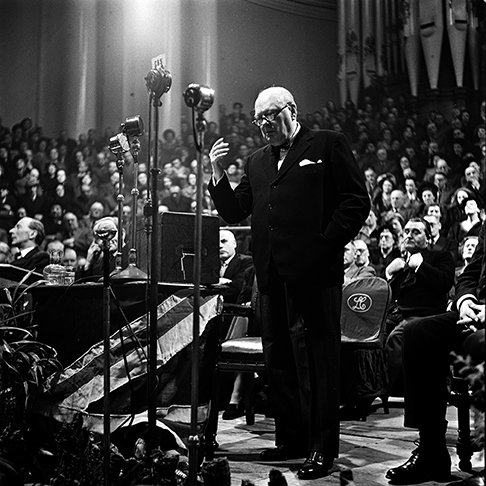

Winston Churchill remained in his seat for more than sixty years, but his career as a public person is, funnily and uncommonly enough, less remarkable for his duration than his brightness. He served, always before the usual practice, many ministerial positions and peaked a cursus honorum, of Defence of Ammunition, of Admiralty of the Air Ministry, from Minister of the Colonies to Home Minister. He was also appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer, despite his wasteful habits. Likewise, he became a memorable speaker despite having a speech impediment in pronouncing the letter “s”. Unsurprisingly —since his character was his main target—in his six-decade career in the political arena, he faced success and failure, and only rarely, discipline.

Historian John Lukacs, a prodigal in the figure of Churchill, analyses his career before the Second World War: by contrast to his warlike performance, his previous history was peppered with substantial errors. His position as regards the abdication of Edward VII was criticized, as well as his staunch imperialist position against India’s independence, again harshly criticized. Be that as it may, his greatest bloodstained mistake is called Gallipoli, all the more serious in that it followed from his own stubborn refusal to abandon the campaign. Over a quarter of a million soldiers died, as a consequence, and his Admiralship followed this downward fall. Unsuccessfully, he tried to claim his visionary profile: his prophetical demands of re-arming to defeat the Germans before the Great War, his support of petrol before coal, his spearheading use of tanks and even his early opposition —“strangled in its cradle”— to Bolshevism. Gallipoli would condemn him to prostration and silence, yet his lucidity intact: according to his wife, Clementine, the heavy weight of deaths and defeat came close to killing him with sorrow.

That was the first penitentiary station suffered by Winston Churchill. The bitterest of them all was endured in the 1930s: a pariah, isolated, and very little connivance, he became a prophet in the desert before the budding incubation of the Nazi emergence. This is when he arose as an early alert to the danger posed by Hitler, when even the Duke of Windsor —momentarily King Edward VIII— openly admired the German dictator, and the English high classes showed their sympathy towards him and Neville Chamberlain was applauded by the masses as a Man of Peace. Delving into the Churchillian character, historian Michael Burleigh argues that one must have something evil inside to have the capacity to recognize the emergence of something equally evil, at such an early stage, like the National Socialist regime. At least, the man who had defeated “the darkest desperation”, as doctor Moran well knew, managed to convince the others that desperation could be defeated. In May 1940, Churchill was about to know his “best time”: facing ambiguous pacts, he managed to instil on his cabinet his thesis of fighting Hitler, and history finally tilted on his side.

This story is yet unwritten. In his inauguration speech, Churchill anticipated his offering to the English people, “blood, sacrifice, tears and sweat”. As usual in his political career, his appearance on scene was an amazing providence of the best opportunity: his speeches still resound today as a vital reason and helped clear up scepticism and galvanize a whole country that would also get acquainted with “his best time” in the face of the night-time Blitz air raids. His words have become a world heritage in the history of human memory: “We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender”. Churchill was subjected to criticism even by the conservatives —Freemason, daredevil, Americanoid, involved in Communism—, but on fighting against Nazi totalitarianism, he was convinced that he fought against the madness of chaos whose target was to blast away the very foundations of civilization.

Churchill was, precisely, “Hitler’s antagonist”, the embodiment —says Lukacs— of resistance of an ancient world, of ancient liberties and ancient laws against a man who embodied efficient, brutal and modern power. Churchill was aware that there was an end to the game: not only the role of his own nation among world powers but also the role of a time in the world that had begun centuries before he was born. This is why he personified the role of “defender of civilization” in crucial historical times: Churchill knew that Great Britain could resist but not defeat Hitler. First of all, he knew that the Nazis could win the war. Nowadays, this threat tends to be forgotten. The real battle was —according to Lukacs— between a revolutionary Hitler and a conservative Churchill.

Churchill’s achievement in the war —says Burleigh— boils down to his leading role of his people and, later on, his guarantee of the participation in the warlike endeavour of its American ally. Deep inside, there was a moral dilemma: the entire continent under the Nazis or half of the continent under Soviet rule. Eventually, the man who, under the steely tempest of the bombings, boldly rose up to the rooftop of Downing Street, used, for the first time, the two-fingered V for victory sign. But there is some melancholy history on remembering that, by 1945, Churchill had already given orders to draft an attack against Stalin. The country was exhausted. From “Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic”, an “iron curtain” fell over Europe.

On losing the general elections, two months after Victory Day, Winston Churchill managed to conclude that “all great nations are ungrateful”. Here began a withdrawal and his twilight. On his downhill slope, he made yet one last attempt —from 51 to 55— to become Great Britain’s PM again. After that, he was dedicated to writing books, his watercolour paintings, his masonry works, going on a cruise in Onassis yacht. Exhausted and nearly terminally ill, always close to whisky, which he used as a light mouthwash, Churchill sadly saw the British Empire settle in darkness. In the end, he broke his hip and was appointed honorary citizen of the United States —the first since Lafayette— and sat for the last time in the House of Commons in the summer of 1964. He was months away from his death. The journalist Augusto Assía, who had been in close contact with him, wrote amidst the Blitz air raids that, even without war, Churchill “would have gone down in history as one of the most powerful, dazzling and versatile figures of the British panorama”. His was “the nerve of the great Elizabethan characters”.

Yet one more of his heterodoxies —heavy drinker and smoker— was living beyond ninety years of age, but a character like Churchill’s gave meaning and coherence to any contradiction. The boy who struggled with Latin in Harrow would become a magnificent English writer. The hero laureate in three continents would end his days with the high profile of the great statesmen. His temper relentlessly chased by the “black dog” of melancholy would also be the temper that allowed him to surrender to the charms of a bottle of Pol Roger champagne. Certainly, it is ironical to think that the person responsible for the Gallipoli defeat would one day herald the victory from one of the balconies in Whitehall. Wavering between liberal and conservative —in fact, a tribute to conciliation between opposing positions—, all opposing views were successfully solved. For example, Churchill has been described as the jealous guardian of atavistic English liberties, but, what would have become of old Europe, had he also been a dedicated Francophile? On 31 January 1965, the London citizens bore witness to that, on seeing, at Saint Paul’s funeral, the profile of general Charles de Gaulle. They were the architects of a reconciled Europe, the spirit of a entente cordiale of sorts. Churchill, de Gaulle, both had been together in times of “triumph and tragedy”. Both well knew, in all fairness, about power and glory.

The City is concealed behind its best fog, the bells inside the Big Ben remain silent and the cranes over the river Thames bowed in respect at the passage of the entourage of the funeral for Winston Churchill. It was on 31st January 1965, and that was a grand occasion. London —as chroniclers report— had never seen anything like this since the time of Gladstone as a Prime Minister. Nor would they see it again: the solemn funeral for this great statesman would be the last one displaying “the British tradition of imperial ceremony”. The arrangements for the funeral had been carefully set out by Elizabeth II: slow liturgy, restrained grief, subdued pomp and the final glorified moment of gun salutes. A true state funeral.

From Saint Paul’s cathedral to Blenheim, this reverence spread across the many English citizens who took the streets to witness the procession. As the coffin proceeded, the bobbies touched their helmet to salute; the civilians took their hats off. Their sorrow was tearless sadness, no unnecessary sobbing, no signs. These were the same old British people described by Orwell, in football stands, as gentle and quiet going to Sunday mass service. On that particular day they were the embodiment of a grateful nation. Many years after that glorious afternoon, one might think that could be an exaggerated propaganda farewell ceremony —as one oblivious historian said— to “that funnily dressed man who drinks wine for breakfast”. Still, those secretaries from the War Office and those East End shop assistants did not have to wonder why they were there. They knew how much they owed this man. Surely, some of them had fought at the other side of the Channel. Many had lived, in the same streets, the Blitz, the “terror bombing”. And they all had found a reason for courage and hope in the voice that, through the BBC, knew how to shout out “we shall never surrender”. In that critical hour of 1940, as Ian Buruma reports, the world had no other handhold than Winston Churchill’s moral vigour. A merciful tribute to his memory was the least they could do.

On facing England’s battle, Store reports, “a leader of sober judgement could have well concluded that there was no hope whatsoever”. Luckily, of all the adjectives describing Winston Churchill, being “sober” is the least frequented of them all. He would always sleep randomly, and his eating habits defied schedule. While labour leader Attlee handled much of the organisational work, Churchill entertained his Chief of the Imperial General Staff until dawn, soaking in scotch and alcoholic loquaciousness. He would smoke between nine and ten cigars a day, had a confessed weakness for vintage brandy and —according to his own estimate— uncorked forty thousand champagne bottles. But perhaps a statesman needs certain virtues in times of peace and others in times of war. Churchill never had a sense of proportion, temperance or moderation. However, leadership was in his blood, the son of an old Marlborough trunk. From his father, he inherited his poise of an Englishman seasoned in Victorian certainties; from his mother, individualist optimism of the Americans of the best age.

He would smoke between nine and ten cigars a day, had a confessed weakness for vintage brandy and —according to his own estimate— uncorked forty thousand champagne bottles

That’s the origin of the noblesse oblige of the aristocrat, ensued by the political gift of opportunity, the foresight of the military and the instinct of a historian. Yet one more trait of character can be accredited to his lineage: a blend between audacity and recklessness probably dating back to a genetic origin between Raleigh and Drake, which would distinguish him from contemporary politicians.

On studying the Churchillian temperament, lord Owen, therefore, hits the nail on the head about his caveat: when talking about Winston Churchill, nobody should think about him about a standard person. His enemies, e.g. Hitler, were by no means standard, either. Nor was his life standard, a life that saw the last cavalry charge and the initial steps of the space race, the rise and fall of the British Empire, the discredit and the popularity and —in his own words— “triumph and disaster”. From both ends, he emerged victorious in the Second World War, held innumerable high-profile positions, set standards as a historian, was awarded the Nobel Prize of Literature and gave name to hallmark Cuban cigar and polka-dot bow ties. For any man, fighting in the three continents or enjoying journalistic celebrity would have meant a vital achievement: in Churchill’s biography, these rank as minor glories.

Many have tried to assess Churchillian grandeur. Phyllis Moir, one of Churchill’s secretaries, was insistently asked about this. The good old woman devoted years to come up with an answer. In the end, she wrote that “it was impossible to work with Mr. Churchill for some time without having the feeling that he was a predestined man”. It is difficult to read things like that in writings by political scientists. But when Moir portrays Churchill as someone working non-stop and rushing all the time, one can’t help thinking that he was someone urgently trying to accomplish his fate.

His haste was soon revealed. On his admittance to Sandhurst’s Military Academy, young Churchill wrote a letter to his mother expressing his solemn intention to “do something in this world”. The time of the shy child was left behind, as well as the poorly disciplined and unpopular student in Harrow, one of the race’s nurseries. “Doing something in this world”: the same phrase had previously been used by Benjamin Disraeli. Like the eminent Victorian, Churchill would step up the pace to accomplish that end: he may not have a great intellectual background, but what he did have was a magnificent Hussar uniform to honour.

He also had a fearless bravery to the point that one should wonder what would have become of Winston Churchill should he have saved his energy striving for war, instead. His historical background never ceases to astound us. Before turning twenty-five, he had participated in fifty operations with live ammunition in Cuba, India, Sudan, Egypt and South Africa. And he did so, virtually always, by adopting a two-pronged profile, as a soldier and as a journalist, halfway between “making ends meet” and poorly meditated romanticism. Sometimes —like during the Boers war— he was only working as a journalist, but even then managed to get in trouble. For example, in South Africa his train suffered an attack, and Churchill took control of the situation and never received any Victoria Cross (VC), if only as a civilian. Later on, confined in Pretoria, he added more pages onto his heroic young achievements: his escape from a prisoner camp and landing in Lourenço Marques —Mozambique’s capital city, separated by no less than three hundred miles— was received in England as the adventures of a Lord Byron of sorts. With hindsight, these were only the budding stanzas of an epic drama.

No Churchill, the statesman, would have ever existed, without the existence of a previous Churchill, the soldier. Therefore, Churchill’s return to the military life should not come as a surprise: after his early and frustrated adventure in Oldham, in the late 19th century, came his participation in the Great War, at breakneck speed, as a sign of atonement after his military debacle in Gallipoli. But South Africa had been his revelation to the world and, the resulting popularity projected him to politics: by the wake of the new century Churchill had become an MP. Shortly before, he had turned to his mother: “I telegraphed her and asked her to send me books”. It was this pragmatism that shaped the prose of a historian on Gibbon’s lined sheets and —according to Bernard Shaw— the greatest stylist of England of his time.

Winston Churchill remained in his seat for more than sixty years, but his career as a public person is, funnily and uncommonly enough, less remarkable for his duration than his brightness. He served, always before the usual practice, many ministerial positions and peaked a cursus honorum, of Defence of Ammunition, of Admiralty of the Air Ministry, from Minister of the Colonies to Home Minister. He was also appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer, despite his wasteful habits. Likewise, he became a memorable speaker despite having a speech impediment in pronouncing the letter “s”. Unsurprisingly —since his character was his main target—in his six-decade career in the political arena, he faced success and failure, and only rarely, discipline.

Historian John Lukacs, a prodigal in the figure of Churchill, analyses his career before the Second World War: by contrast to his warlike performance, his previous history was peppered with substantial errors. His position as regards the abdication of Edward VII was criticized, as well as his staunch imperialist position against India’s independence, again harshly criticized. Be that as it may, his greatest bloodstained mistake is called Gallipoli, all the more serious in that it followed from his own stubborn refusal to abandon the campaign. Over a quarter of a million soldiers died, as a consequence, and his Admiralship followed this downward fall. Unsuccessfully, he tried to claim his visionary profile: his prophetical demands of re-arming to defeat the Germans before the Great War, his support of petrol before coal, his spearheading use of tanks and even his early opposition —“strangled in its cradle”— to Bolshevism. Gallipoli would condemn him to prostration and silence, yet his lucidity intact: according to his wife, Clementine, the heavy weight of deaths and defeat came close to killing him with sorrow.

That was the first penitentiary station suffered by Winston Churchill. The bitterest of them all was endured in the 1930s: a pariah, isolated, and very little connivance, he became a prophet in the desert before the budding incubation of the Nazi emergence. This is when he arose as an early alert to the danger posed by Hitler, when even the Duke of Windsor —momentarily King Edward VIII— openly admired the German dictator, and the English high classes showed their sympathy towards him and Neville Chamberlain was applauded by the masses as a Man of Peace. Delving into the Churchillian character, historian Michael Burleigh argues that one must have something evil inside to have the capacity to recognize the emergence of something equally evil, at such an early stage, like the National Socialist regime. At least, the man who had defeated “the darkest desperation”, as doctor Moran well knew, managed to convince the others that desperation could be defeated. In May 1940, Churchill was about to know his “best time”: facing ambiguous pacts, he managed to instil on his cabinet his thesis of fighting Hitler, and history finally tilted on his side.

This story is yet unwritten. In his inauguration speech, Churchill anticipated his offering to the English people, “blood, sacrifice, tears and sweat”. As usual in his political career, his appearance on scene was an amazing providence of the best opportunity: his speeches still resound today as a vital reason and helped clear up scepticism and galvanize a whole country that would also get acquainted with “his best time” in the face of the night-time Blitz air raids. His words have become a world heritage in the history of human memory: “We shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be, we shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender”. Churchill was subjected to criticism even by the conservatives —Freemason, daredevil, Americanoid, involved in Communism—, but on fighting against Nazi totalitarianism, he was convinced that he fought against the madness of chaos whose target was to blast away the very foundations of civilization.

Churchill was, precisely, “Hitler’s antagonist”, the embodiment —says Lukacs— of resistance of an ancient world, of ancient liberties and ancient laws against a man who embodied efficient, brutal and modern power. Churchill was aware that there was an end to the game: not only the role of his own nation among world powers but also the role of a time in the world that had begun centuries before he was born. This is why he personified the role of “defender of civilization” in crucial historical times: Churchill knew that Great Britain could resist but not defeat Hitler. First of all, he knew that the Nazis could win the war. Nowadays, this threat tends to be forgotten. The real battle was —according to Lukacs— between a revolutionary Hitler and a conservative Churchill.

Churchill’s achievement in the war —says Burleigh— boils down to his leading role of his people and, later on, his guarantee of the participation in the warlike endeavour of its American ally. Deep inside, there was a moral dilemma: the entire continent under the Nazis or half of the continent under Soviet rule. Eventually, the man who, under the steely tempest of the bombings, boldly rose up to the rooftop of Downing Street, used, for the first time, the two-fingered V for victory sign. But there is some melancholy history on remembering that, by 1945, Churchill had already given orders to draft an attack against Stalin. The country was exhausted. From “Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic”, an “iron curtain” fell over Europe.

On losing the general elections, two months after Victory Day, Winston Churchill managed to conclude that “all great nations are ungrateful”. Here began a withdrawal and his twilight. On his downhill slope, he made yet one last attempt —from 51 to 55— to become Great Britain’s PM again. After that, he was dedicated to writing books, his watercolour paintings, his masonry works, going on a cruise in Onassis yacht. Exhausted and nearly terminally ill, always close to whisky, which he used as a light mouthwash, Churchill sadly saw the British Empire settle in darkness. In the end, he broke his hip and was appointed honorary citizen of the United States —the first since Lafayette— and sat for the last time in the House of Commons in the summer of 1964. He was months away from his death. The journalist Augusto Assía, who had been in close contact with him, wrote amidst the Blitz air raids that, even without war, Churchill “would have gone down in history as one of the most powerful, dazzling and versatile figures of the British panorama”. His was “the nerve of the great Elizabethan characters”.

Yet one more of his heterodoxies —heavy drinker and smoker— was living beyond ninety years of age, but a character like Churchill’s gave meaning and coherence to any contradiction. The boy who struggled with Latin in Harrow would become a magnificent English writer. The hero laureate in three continents would end his days with the high profile of the great statesmen. His temper relentlessly chased by the “black dog” of melancholy would also be the temper that allowed him to surrender to the charms of a bottle of Pol Roger champagne. Certainly, it is ironical to think that the person responsible for the Gallipoli defeat would one day herald the victory from one of the balconies in Whitehall. Wavering between liberal and conservative —in fact, a tribute to conciliation between opposing positions—, all opposing views were successfully solved. For example, Churchill has been described as the jealous guardian of atavistic English liberties, but, what would have become of old Europe, had he also been a dedicated Francophile? On 31 January 1965, the London citizens bore witness to that, on seeing, at Saint Paul’s funeral, the profile of general Charles de Gaulle. They were the architects of a reconciled Europe, the spirit of a entente cordiale of sorts. Churchill, de Gaulle, both had been together in times of “triumph and tragedy”. Both well knew, in all fairness, about power and glory.