In Stuttgart there are two imposing museums for two leading...

In 2050 the self-driving car will be a reality that...

The Sant Martí facility wins the award shortly after its...

When Rupert and Kristin Isaacson saw Rowan, their son with...

Just as in the universe there are so many planets...

Carlos Pazos, a modern-day dandy born in Barcelona in 1949...

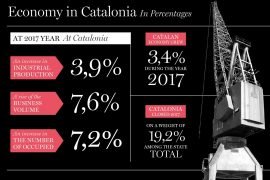

The Catalan economy grew 3.4% in 2017 according to estimates...

The Museu Marítim will host on October 28 the great...

The audiovisual sector has a motto that will always prevail:...

Its first 'boutique' in Barcelona will open on the ground...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

On the first day of the year 1959 La Vanguardia published a series of reviews about the previous year. These texts pivoted around national politics, theatre or literature or the economic situation in Spain, towards which such technocrats as Ullastres and Navarro Rubio are contributing to — as their programme aims to stabilise public finances and avoid the breakdown of the Francoist dictatorship. After those initial pages, there was an article that looked ahead, and was signed with the initials S.N. Santiago Nadal —in charge of the paper’s international section— was not allowed by the director Luis de Galinsoga to sign his articles and reviews with his name. But everyone knew who the author was. Nowadays, however, the worth of his journalistic corpus is forgotten or kept at bay by prejudice. The tradition of postwar democratic liberalism remains unassumed.

On the first day of the year 1959 La Vanguardia published a series of reviews about the previous year. These texts pivoted around national politics, theatre or literature or the economic situation in Spain, towards which such technocrats as Ullastres and Navarro Rubio are contributing to — as their programme aims to stabilise public finances and avoid the breakdown of the Francoist dictatorship. After those initial pages, there was an article that looked ahead, and was signed with the initials S.N. Santiago Nadal —in charge of the paper’s international section— was not allowed by the director Luis de Galinsoga to sign his articles and reviews with his name. But everyone knew who the author was. Nowadays, however, the worth of his journalistic corpus is forgotten or kept at bay by prejudice. The tradition of postwar democratic liberalism remains unassumed.

One of his articles is a good example of this. In “El año en que entramos” [This coming year] the monarchical Nadal, evolved from reactionarism to conservative liberalism, spoke about the crisis in the city of Berlin. In the capital of the Cold War, the stubborn political blockage was in danger of turning into an explosive short-circuit. This was the main threat against the great continental project, set in motion in 1959: the European Economic Community. The creation of the EEC was the result of the signature of the Treaty of Rome in March 1957. The leaders of the undersigning countries —Federal Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands— agreed to a series of economic measures that would “consolidate, through the constitution of a series of actions, the defence of peace and freedom”, quoting the preamble of the Treaty. On 1st January 1959, says Nadal, the implementation of the first decision from the treaty took place: the member states lowered by 10% their customs tariffs, then this measure gradually extended to reach the total suppression of customs tariffs. Towards the Union, then, through economy.

As customs offices gradually were losing their function, it would appear that the European project would mature. Its strengthening was needed for geopolitical reasons, mainly. Santiago Nadal said: “The progressive integration of Europe is an actual need originating from unsurmountable realities. Over these realities, the main one being: the existence of two colossal non-European blocks, whose existence, even disregarding their rivalries, would force, nearly as a law of physics, the tiny European states to get together and set up some sort of union”. Let’s call it a common market, or a European Economic Community. Its creation, on the basis of a progressive ideology, and its materialization through a series of economic agreements, cannot be understood outside this critical context. On the one hand, the catastrophic end of the European Civil war. While after the Great War Europe had failed in building up a new order, after 1945 the consolidation of a long-lasting peace required thorough reconsideration of the idea of Europe. On the other hand, the Cold War. The new idea of Europe should take shape in an unprecedented global situation: the ongoing and threatening tension between the US and the Soviet block. What would later become the European Union arose from this international context. But when these critical circumstances disappeared, the European project had to adapt to new coordinates. Luckily, the coordinates did change. The most obvious and iconic evidence of this was the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It was in this “Ciceronian moment”, fully conscious of the worldwide transformation that was to come, that in summer 89 Francis Fukuyama published his article “The End of History” in The National Interest, the magazine on international issues co-founded by Irving Kristol —one of the eminent thinkers of US neoconservatives— and Henry Kissinger among its main landmarks. The proposal, with a similar incidence in the Spanish arena —with an atonic right and a rusty left—, brought about the restructure of the world after the disappearance of the Soviet dictatorship. Amidst the implosion of the communist block, a victorious feeling exudes from Fukuyama’s article, peppered with sarcasm. “The resulting emerging State is liberal, as it recognizes and protects, through a legal system, the universal right of man to freedom. This State is also democratic because it exists only with the consent of the governed”. The incarnation of that State, said the politologist, were the states of Western Europe who had created the common market.

And now, what remains from a legacy drafted at the peak of intellectual legitimacy of conservatism? Like a bulldozer, the financial crisis has run over this thinking: the world coordinates have changed again. Perhaps it was too soon to draft a realistic formula that would threaten globalization. Be that as it may, the adequacy of a European project to the new coordinates resulting from globalization has not occurred convincingly. History reappears on scene and Europe, so it seems, is conceived as if it were living in the past.

On the first day of the year 1959 La Vanguardia published a series of reviews about the previous year. These texts pivoted around national politics, theatre or literature or the economic situation in Spain, towards which such technocrats as Ullastres and Navarro Rubio are contributing to — as their programme aims to stabilise public finances and avoid the breakdown of the Francoist dictatorship. After those initial pages, there was an article that looked ahead, and was signed with the initials S.N. Santiago Nadal —in charge of the paper’s international section— was not allowed by the director Luis de Galinsoga to sign his articles and reviews with his name. But everyone knew who the author was. Nowadays, however, the worth of his journalistic corpus is forgotten or kept at bay by prejudice. The tradition of postwar democratic liberalism remains unassumed.

On the first day of the year 1959 La Vanguardia published a series of reviews about the previous year. These texts pivoted around national politics, theatre or literature or the economic situation in Spain, towards which such technocrats as Ullastres and Navarro Rubio are contributing to — as their programme aims to stabilise public finances and avoid the breakdown of the Francoist dictatorship. After those initial pages, there was an article that looked ahead, and was signed with the initials S.N. Santiago Nadal —in charge of the paper’s international section— was not allowed by the director Luis de Galinsoga to sign his articles and reviews with his name. But everyone knew who the author was. Nowadays, however, the worth of his journalistic corpus is forgotten or kept at bay by prejudice. The tradition of postwar democratic liberalism remains unassumed.

One of his articles is a good example of this. In “El año en que entramos” [This coming year] the monarchical Nadal, evolved from reactionarism to conservative liberalism, spoke about the crisis in the city of Berlin. In the capital of the Cold War, the stubborn political blockage was in danger of turning into an explosive short-circuit. This was the main threat against the great continental project, set in motion in 1959: the European Economic Community. The creation of the EEC was the result of the signature of the Treaty of Rome in March 1957. The leaders of the undersigning countries —Federal Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg and the Netherlands— agreed to a series of economic measures that would “consolidate, through the constitution of a series of actions, the defence of peace and freedom”, quoting the preamble of the Treaty. On 1st January 1959, says Nadal, the implementation of the first decision from the treaty took place: the member states lowered by 10% their customs tariffs, then this measure gradually extended to reach the total suppression of customs tariffs. Towards the Union, then, through economy.

As customs offices gradually were losing their function, it would appear that the European project would mature. Its strengthening was needed for geopolitical reasons, mainly. Santiago Nadal said: “The progressive integration of Europe is an actual need originating from unsurmountable realities. Over these realities, the main one being: the existence of two colossal non-European blocks, whose existence, even disregarding their rivalries, would force, nearly as a law of physics, the tiny European states to get together and set up some sort of union”. Let’s call it a common market, or a European Economic Community. Its creation, on the basis of a progressive ideology, and its materialization through a series of economic agreements, cannot be understood outside this critical context. On the one hand, the catastrophic end of the European Civil war. While after the Great War Europe had failed in building up a new order, after 1945 the consolidation of a long-lasting peace required thorough reconsideration of the idea of Europe. On the other hand, the Cold War. The new idea of Europe should take shape in an unprecedented global situation: the ongoing and threatening tension between the US and the Soviet block. What would later become the European Union arose from this international context. But when these critical circumstances disappeared, the European project had to adapt to new coordinates. Luckily, the coordinates did change. The most obvious and iconic evidence of this was the fall of the Berlin Wall.

It was in this “Ciceronian moment”, fully conscious of the worldwide transformation that was to come, that in summer 89 Francis Fukuyama published his article “The End of History” in The National Interest, the magazine on international issues co-founded by Irving Kristol —one of the eminent thinkers of US neoconservatives— and Henry Kissinger among its main landmarks. The proposal, with a similar incidence in the Spanish arena —with an atonic right and a rusty left—, brought about the restructure of the world after the disappearance of the Soviet dictatorship. Amidst the implosion of the communist block, a victorious feeling exudes from Fukuyama’s article, peppered with sarcasm. “The resulting emerging State is liberal, as it recognizes and protects, through a legal system, the universal right of man to freedom. This State is also democratic because it exists only with the consent of the governed”. The incarnation of that State, said the politologist, were the states of Western Europe who had created the common market.

And now, what remains from a legacy drafted at the peak of intellectual legitimacy of conservatism? Like a bulldozer, the financial crisis has run over this thinking: the world coordinates have changed again. Perhaps it was too soon to draft a realistic formula that would threaten globalization. Be that as it may, the adequacy of a European project to the new coordinates resulting from globalization has not occurred convincingly. History reappears on scene and Europe, so it seems, is conceived as if it were living in the past.