Approved by the Executive Committee, the principles underscore gender equality...

The CEO of Acció, Albert Castellanos, and the president of...

Animac, scheduled for the 22nd to 25th of February in...

La universidad norteamericana publica un caso de estudio que analiza...

CosmoCaixa commemorates the half century of the arrival to the...

Research data confirm that physical exercise inactivity is a serious...

Organisations don't last forever: they are born, live and die....

The New York Times, with a total of 125 awards,...

The successful Mobile World Congress held recently in Barcelona has...

The company settled in the Baix Empordà manufactures up to...

Como bien nos recordaba Irene Vallejo en su Manifiesto por...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

[dropcap letter=”A”]

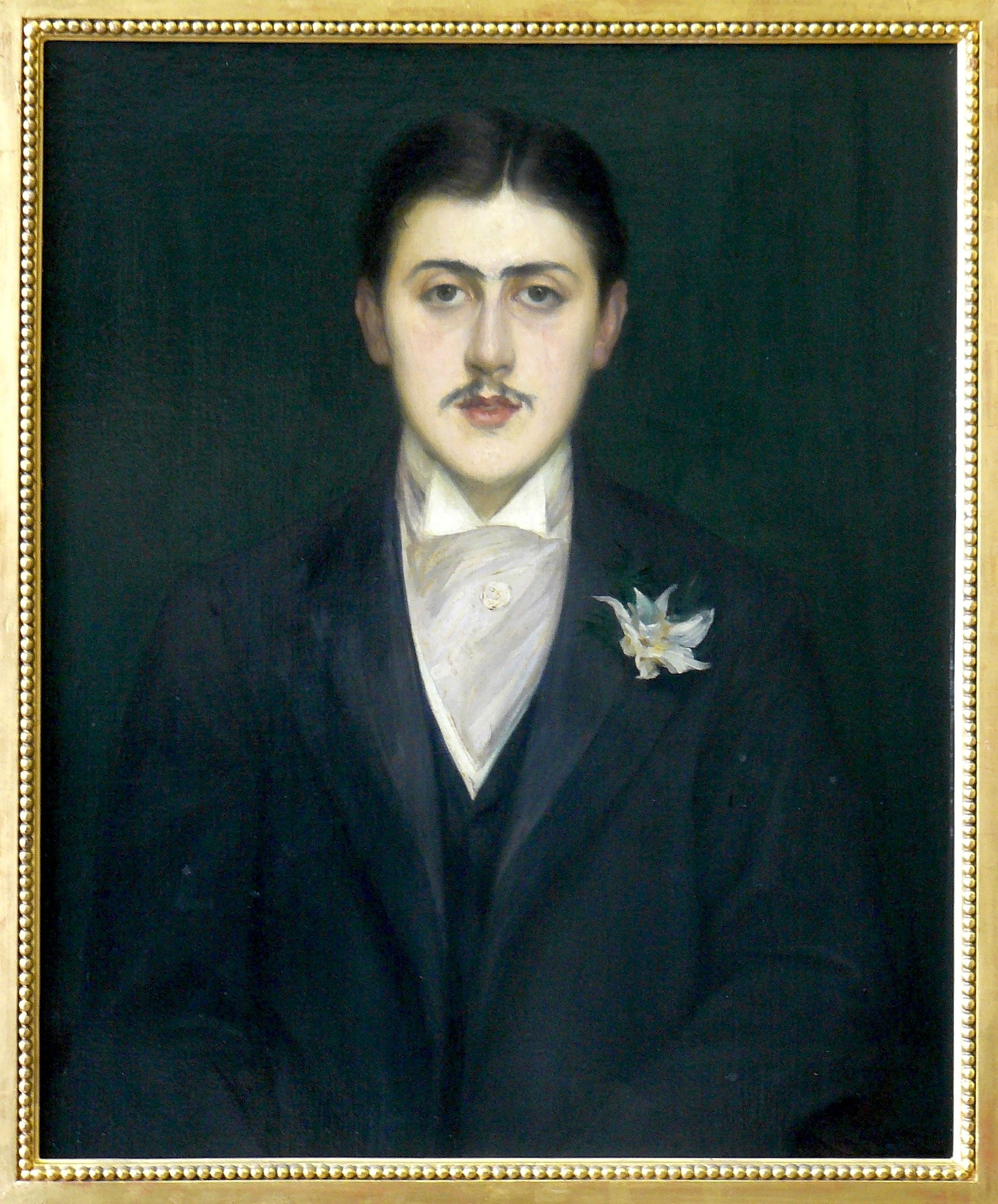

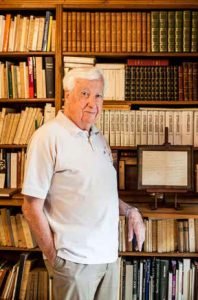

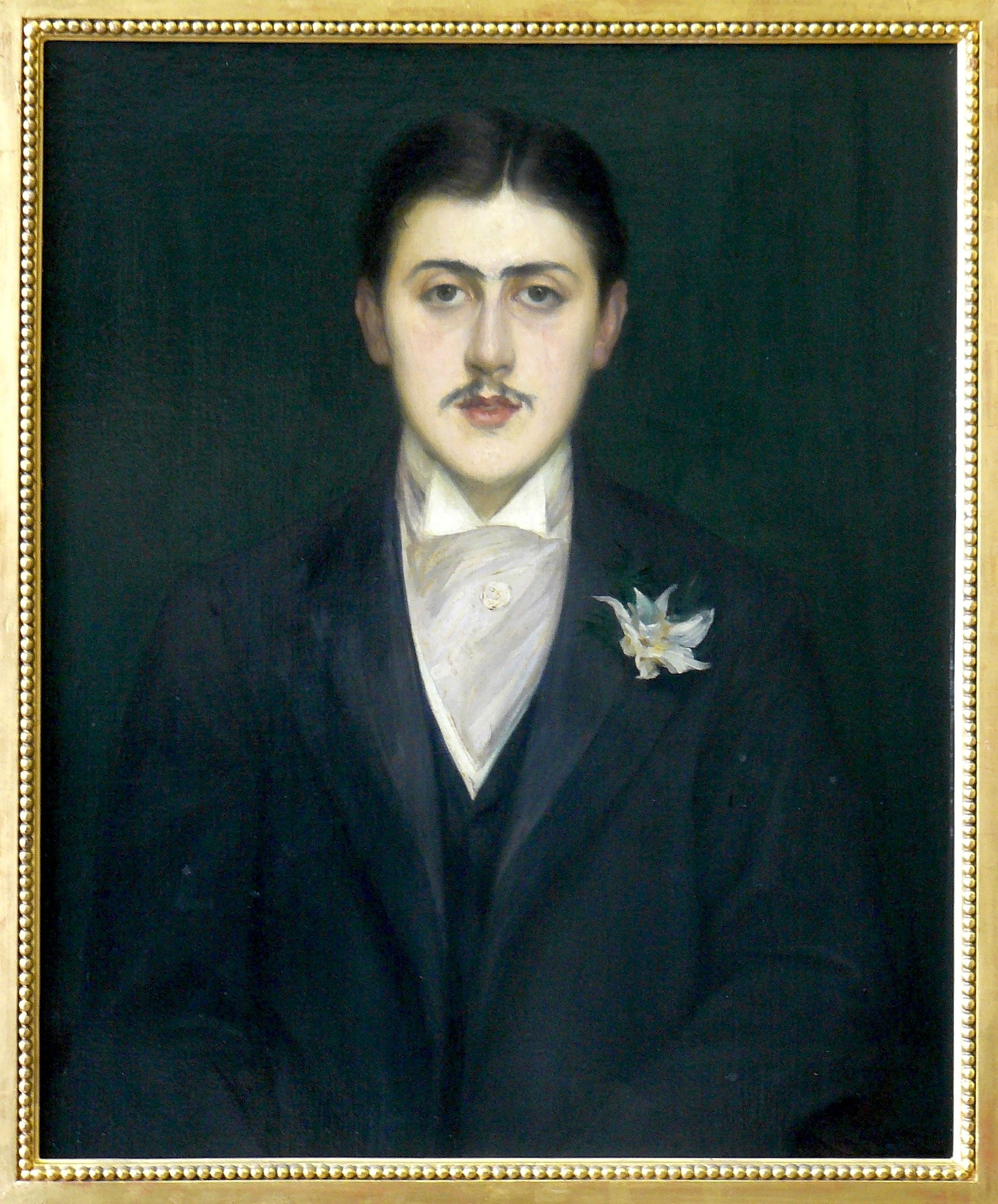

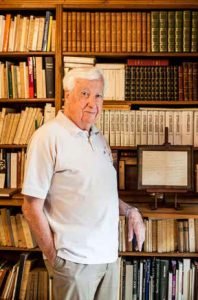

madeu Cuito, eminent Proustian, was born in Barcelona in a Catalan and liberal family who went on exile to France after the Spanish Civil War. He lives in Perpignan and Paris, where he is studying law and economy. After New York and Madrid, he has been living in Barcelona since 1976. Author of El jardí sense temps [Garden without Time], Contes d’un carrer estret [Stories of a Narrow Street] and Memòries d’un somni [Memories of a Dream]. Presides over the Society of Friends of Marcel Proust.

Why reading Proust in 2016?

Reading Proust means opening the door to a unique world. His poetry equals great literature and, from a viewpoint that is by no means determining, nowadays reading him can be inconsistent with Twitter’s immediacy because Proust speaks about an elongated time, about eternity and also about the destructive capacity of time. He stated: “True life, life discovered and cleared, at last, therefore the only one actually lived, is literature”. This is so in the 20th or the 21st century. Nowadays, the issue at stake is tempo. Whoever feels passion for reading, for living literature, will have time to read Proust. And this has continuity, although in In Search of Lost Time is a book that must be read from cover to cover, thirteen volumes, with a beginning and an end. It hinges on the 19th century and, in many respects, it is structured like classical novels. Contrary to what people think, the work has a plot. He speaks about his useless years until he finally discovered “his invisible vocation”, of whose period In Search is his own story. However, the reader must understand that Proust gives dynamism to description and, therefore, description becomes the real action. When you understand that, Proust becomes an unlimited territory.

Does online reading, digital immediacy, put up barriers to reading Proust?

This is a problem but not an insurmountable, if we really want to enter the continent of great literature. Certainly, Proust’s world exists in contrast to swiftness. It is, say, a system of descriptions apparently static but plot-weaving, characters of contradictory identities, perceptions of all types, constant time transitions. Everything intertwined by an artifice of symmetries and perfections. And reading Proust requires time. The basic reason for a work of art —like Proust— is giving pleasure, spiritual pleasure. This is like One thousand and one nights with time and its relentlessness —supervisory divinity interpreted by the narrator— which eventually reveals the worm-eaten faces of the characters. Here is a novel like an invisible world, in contrast with the novel-mirror, according to Stendhal.

Pelazzi]

Like any literary work, In Search of Lost Time has one first reading —that of youth, after adolescence— and then readings made in adulthood. The first time, it must be read from the beginning to the end. Then comes the re-reading and, at this stage, it is not necessary to do it as a linear reading. With the characters and topics in your memory, you can choose and savour those bits that brought you back to secret landscapes by Proust, and there you will find new insights. There is a philosophy of time, the Proust with a sense of humour that is not always taken into account. There is the analysis of jealousy, the ambivalence of human relations, the power of names, the transcendence of art. A compelling truth is that it is a novel that alludes to immediacy, personally. It makes you talk to yourself, despite speaking from a time that nowadays feels distant. This is irrelevant because what is important is that it will lead you to talk to yourself, from Swann’s Way to Time Regained. It is an undeniable argument that the novel is the literary vocation of the main character.

When is your first contact with Proust’s work?

My father could speak French correctly and it was him who grew more enthusiastic about Proust’s work. He liked me to read Proust aloud, because of my Parisian accent. Before, I would read it with special attention to punctuation, an essential resource in Proust’s work. This looked like a perfect way to hate Proust but one day I read it on my own which I’ve done, since then. I was in Paris and must have been 17-18 years old. The first reading is from that time. It’s been many years since nothing that has to do with Proust feels alien to me. This is why I wrote La biblioteca proustiana de Ferran Cuito [Ferran Cuito’s Proust’s Library], to pay tribute to my father.

How can Proust change our lives?

After reading Proust for the first time, comes the reading of someone who has suffered the same disappointments as everyone. This is essential because it requires having a certain degree of maturity in order to fully grasp the novel, every topic, every episode, every character. The other day, a friend of mine, opera director, talked to me about his mother’s death and made a note of reading again the part about the grandmother’s death in In Search, as it is, deep inside, his mother’s death. I was revisiting an extraordinary dramatization. People coming in and out, and every character is sketched out with a distinctive touch. It is not a coincidence that my friend had the same experience.

Nowadays, Proust’s homosexuality is known. Does the fact that the protagonist’s lovers are male turned into female characters maintain credibility?

This is yet another intricacy of In Search. He lived homosexuality like this condition was lived at the time, like a simulation or guilt, unlike the vindictive nature of André Gide. But the female characters are greatly profiled, they are intensely unforgettable. The novel was made in 1913, virtually finished, but its publication was interrupted by the war, and he broke up with his secretary —and lover—, who escapes and dies in an accident. And this traumatizes Proust, and then writes The fugitive and then The prisoner. He is looking back. According to Proust, there is no love without jealousy. He makes up the character of Albertine and the fact of reintroducing it within the novel from the beginning forces him to rewriting almost all the novel and introduces the character into the novel. Throughout the first part, the narrator’s alter ego is Swann, who has an affair with the popular Odette. In the second part, his alter ego is Charlus. These are the outstanding Proustian symmetries, of a work constructed inch by inch, with an extremely precise constructive and architectural rigour. These thousand symmetries are unique. There is the part de Guermantes and the part of Swann, these correspondences are comparable to the structure of a cathedral. In sum, the novel is composition. At the moment of composing In Search, he fights against time and disease.

How do Proust’s characters come in and out?

The origin of the novel is the essay Against Sainte-Beuve. This is the true embryo of In Search. It begins with a first part of memories and reminiscences and about writing how to write, according to how he understands literature. He goes onto a dialogue about refuting ideas from the critic Sainte-Beuve. At the end of the day, what allows him to write a novel? It is the invention of this ambiguous unknown character, someone with no name and yet has two voices. That is, there are two characters: the “I” who explains a series of adventures and the other one, also himself, who appears from time to time. Then, both voices split up. There is one voice that makes comments, draws conclusions, tries to draft laws, makes mistakes, someone who gets back until, at the end, draws a conclusion over what is really a work of art. That is, the key to his vocation. Everything starts again. In sum: “The truth does not begin until the writer takes two different objects, establishes their relationship and binds them with an indestructible link of an alliance of words”. Without it, there is no literature. And, at the same time, the visible world is not the real world. We live within waves of memory. In the end, only metaphor can give eternity to style, said Proust in one of his last essays.

How does theory intervene in memory?

My good friend, the novelist Claude Simon, Nobel Prize for Literature, used to say that when you read the description of an injured body, the blood is not poured on you. If you read about a fire, you don’t get burned. The word fire is not a fire. The subtle shrewdness and the great virtue of Proust’s is that he knows that words are deceiving and that, in order to discover the reality behind an object or a feeling, one must proceed through metaphors. This is something quite general at the time. Tocqueville writes about American democracy and, in fact, is writing about a European or French democracy. This is how Proust conceives that motivations of human beings can produce effects contrary to purposes. To reconstruct another reality, he knows —and insists— that the visible world is inexistent. To understand it, we must create another one and that is possible thanks to the evoking power of words. The narrator is faced with the lost time, and return to fortuitous, involuntary reminiscences. The involuntary memory. The unconscious memories, he says.

Proust was never interested much in politics… but what did he believe in?

We must remember that he was Jewish, French, and therefore, extremely integrated as an assimilated Jew. He knows religion, but has not lived it. And this allows him to assimilate everything from a more isolated and critical viewpoint. Politically, I believe he was a liberal man. He favours Dreyfus, a famous case that divided France. He has an idea of France, which is far from chauvinistic. Even with the Great War, he tries not to fall into the total rejection of German civilization, like others did. In view of this, some consider that Proust was not a very good French, probably with an “antisemitism” of sorts.

What is Proust’s view like, how does he see his characters?

He is merciless. He is direct, realist. Some characters are cruel, but this cruelty can result from a few descriptions about the French society and is always counteracted by the positive part. Merciless, he is. The decadence of the last volume is the relentless passage of time that destroys everything. The last dance of de Guermantes opens up the door and meets the devastating result of the passage of time.

From the religious viewpoint, his religion is art.

It is said that he was a mystic. I believe he was not religious, neither Catholic nor Jewish but he was aware of religions. He reads Pascal, the Bible. But his life is art and his salvation is writing and creating a work of art. This is the only thing that allows him to fight against time because, in the end, will remain.

When does Proust decide to become a writer?

When he was young, he had a vocation to write. He searches for his way and, deep inside, his life is a search of this way, he searches for it through authors he reads and the critics. He tries to do literary criticism, writes pastiches and the novel Jean Santeuil, a primal version and very incomplete of In Search. Was he a snob? He was living in a time when there is a shift in society, aristocracy disappears and the middle class breaks in, another great Proustian symmetry that culminates when the narrator goes back to Paris, after staying in a health centre. The princess de Guermantes invites him to her salon. There he finds again other characters from In Search. Self-promotion and decadences, the passage of time dissolves everything.

Is he a ‘voyeur’?

Proust is a voyeur. Let’s go back to the two voices, dissociated: Marcel and the “I” narrator, a voyeur who is not presented and nobody knows who he is. It is an ambiguous character with an extraordinary capacity to analyze people and social situations, and analyses it with an extraordinary sharpness. He is a voyeur not only of sinful scenes but also of society. He scrutinizes everything, and the result is great literature.

There is a moment between ‘Jean Santeuil’ and ‘In Search’ in which Proust gains a special insight into human nature…

Young Marcel Proust finds his way in the shadows and searches for his way. I think Proust is Proust whenever he invents the character of the narrator. The narrator —he says— explains and says “I”. The narrator who says “I” and is not always “I”. When he meets the narrator, he finds the key to writing a novel. This is the solution that allows him to enter and build the novel. And, I believe, this happens when he finishes Jean Santeuil and realizes that this does not work. He needed to discover the tone and the structure. Proust finds the tone when he becomes aware that another narrator can well exist. And, then, these two voices will lead the novel.

If we read ‘In Search of Lost Time’, do we find the keys to understand the current world?

Proust is contemporary when he criticizes society and its changes, and these changes are thought in one direction but often trigger other changes, in a sense that can even be the opposite. This is an unchangeable lesson in Proust’s work, for the last century and the present century. Time lost, time recovered. When you read Proust, and see how a social class supersedes another, is this not the indirect portrait of a society like ours?

[dropcap letter=”A”]

madeu Cuito, eminent Proustian, was born in Barcelona in a Catalan and liberal family who went on exile to France after the Spanish Civil War. He lives in Perpignan and Paris, where he is studying law and economy. After New York and Madrid, he has been living in Barcelona since 1976. Author of El jardí sense temps [Garden without Time], Contes d’un carrer estret [Stories of a Narrow Street] and Memòries d’un somni [Memories of a Dream]. Presides over the Society of Friends of Marcel Proust.

Why reading Proust in 2016?

Reading Proust means opening the door to a unique world. His poetry equals great literature and, from a viewpoint that is by no means determining, nowadays reading him can be inconsistent with Twitter’s immediacy because Proust speaks about an elongated time, about eternity and also about the destructive capacity of time. He stated: “True life, life discovered and cleared, at last, therefore the only one actually lived, is literature”. This is so in the 20th or the 21st century. Nowadays, the issue at stake is tempo. Whoever feels passion for reading, for living literature, will have time to read Proust. And this has continuity, although in In Search of Lost Time is a book that must be read from cover to cover, thirteen volumes, with a beginning and an end. It hinges on the 19th century and, in many respects, it is structured like classical novels. Contrary to what people think, the work has a plot. He speaks about his useless years until he finally discovered “his invisible vocation”, of whose period In Search is his own story. However, the reader must understand that Proust gives dynamism to description and, therefore, description becomes the real action. When you understand that, Proust becomes an unlimited territory.

Does online reading, digital immediacy, put up barriers to reading Proust?

This is a problem but not an insurmountable, if we really want to enter the continent of great literature. Certainly, Proust’s world exists in contrast to swiftness. It is, say, a system of descriptions apparently static but plot-weaving, characters of contradictory identities, perceptions of all types, constant time transitions. Everything intertwined by an artifice of symmetries and perfections. And reading Proust requires time. The basic reason for a work of art —like Proust— is giving pleasure, spiritual pleasure. This is like One thousand and one nights with time and its relentlessness —supervisory divinity interpreted by the narrator— which eventually reveals the worm-eaten faces of the characters. Here is a novel like an invisible world, in contrast with the novel-mirror, according to Stendhal.

Pelazzi]

Like any literary work, In Search of Lost Time has one first reading —that of youth, after adolescence— and then readings made in adulthood. The first time, it must be read from the beginning to the end. Then comes the re-reading and, at this stage, it is not necessary to do it as a linear reading. With the characters and topics in your memory, you can choose and savour those bits that brought you back to secret landscapes by Proust, and there you will find new insights. There is a philosophy of time, the Proust with a sense of humour that is not always taken into account. There is the analysis of jealousy, the ambivalence of human relations, the power of names, the transcendence of art. A compelling truth is that it is a novel that alludes to immediacy, personally. It makes you talk to yourself, despite speaking from a time that nowadays feels distant. This is irrelevant because what is important is that it will lead you to talk to yourself, from Swann’s Way to Time Regained. It is an undeniable argument that the novel is the literary vocation of the main character.

When is your first contact with Proust’s work?

My father could speak French correctly and it was him who grew more enthusiastic about Proust’s work. He liked me to read Proust aloud, because of my Parisian accent. Before, I would read it with special attention to punctuation, an essential resource in Proust’s work. This looked like a perfect way to hate Proust but one day I read it on my own which I’ve done, since then. I was in Paris and must have been 17-18 years old. The first reading is from that time. It’s been many years since nothing that has to do with Proust feels alien to me. This is why I wrote La biblioteca proustiana de Ferran Cuito [Ferran Cuito’s Proust’s Library], to pay tribute to my father.

How can Proust change our lives?

After reading Proust for the first time, comes the reading of someone who has suffered the same disappointments as everyone. This is essential because it requires having a certain degree of maturity in order to fully grasp the novel, every topic, every episode, every character. The other day, a friend of mine, opera director, talked to me about his mother’s death and made a note of reading again the part about the grandmother’s death in In Search, as it is, deep inside, his mother’s death. I was revisiting an extraordinary dramatization. People coming in and out, and every character is sketched out with a distinctive touch. It is not a coincidence that my friend had the same experience.

Nowadays, Proust’s homosexuality is known. Does the fact that the protagonist’s lovers are male turned into female characters maintain credibility?

This is yet another intricacy of In Search. He lived homosexuality like this condition was lived at the time, like a simulation or guilt, unlike the vindictive nature of André Gide. But the female characters are greatly profiled, they are intensely unforgettable. The novel was made in 1913, virtually finished, but its publication was interrupted by the war, and he broke up with his secretary —and lover—, who escapes and dies in an accident. And this traumatizes Proust, and then writes The fugitive and then The prisoner. He is looking back. According to Proust, there is no love without jealousy. He makes up the character of Albertine and the fact of reintroducing it within the novel from the beginning forces him to rewriting almost all the novel and introduces the character into the novel. Throughout the first part, the narrator’s alter ego is Swann, who has an affair with the popular Odette. In the second part, his alter ego is Charlus. These are the outstanding Proustian symmetries, of a work constructed inch by inch, with an extremely precise constructive and architectural rigour. These thousand symmetries are unique. There is the part de Guermantes and the part of Swann, these correspondences are comparable to the structure of a cathedral. In sum, the novel is composition. At the moment of composing In Search, he fights against time and disease.

How do Proust’s characters come in and out?

The origin of the novel is the essay Against Sainte-Beuve. This is the true embryo of In Search. It begins with a first part of memories and reminiscences and about writing how to write, according to how he understands literature. He goes onto a dialogue about refuting ideas from the critic Sainte-Beuve. At the end of the day, what allows him to write a novel? It is the invention of this ambiguous unknown character, someone with no name and yet has two voices. That is, there are two characters: the “I” who explains a series of adventures and the other one, also himself, who appears from time to time. Then, both voices split up. There is one voice that makes comments, draws conclusions, tries to draft laws, makes mistakes, someone who gets back until, at the end, draws a conclusion over what is really a work of art. That is, the key to his vocation. Everything starts again. In sum: “The truth does not begin until the writer takes two different objects, establishes their relationship and binds them with an indestructible link of an alliance of words”. Without it, there is no literature. And, at the same time, the visible world is not the real world. We live within waves of memory. In the end, only metaphor can give eternity to style, said Proust in one of his last essays.

How does theory intervene in memory?

My good friend, the novelist Claude Simon, Nobel Prize for Literature, used to say that when you read the description of an injured body, the blood is not poured on you. If you read about a fire, you don’t get burned. The word fire is not a fire. The subtle shrewdness and the great virtue of Proust’s is that he knows that words are deceiving and that, in order to discover the reality behind an object or a feeling, one must proceed through metaphors. This is something quite general at the time. Tocqueville writes about American democracy and, in fact, is writing about a European or French democracy. This is how Proust conceives that motivations of human beings can produce effects contrary to purposes. To reconstruct another reality, he knows —and insists— that the visible world is inexistent. To understand it, we must create another one and that is possible thanks to the evoking power of words. The narrator is faced with the lost time, and return to fortuitous, involuntary reminiscences. The involuntary memory. The unconscious memories, he says.

Proust was never interested much in politics… but what did he believe in?

We must remember that he was Jewish, French, and therefore, extremely integrated as an assimilated Jew. He knows religion, but has not lived it. And this allows him to assimilate everything from a more isolated and critical viewpoint. Politically, I believe he was a liberal man. He favours Dreyfus, a famous case that divided France. He has an idea of France, which is far from chauvinistic. Even with the Great War, he tries not to fall into the total rejection of German civilization, like others did. In view of this, some consider that Proust was not a very good French, probably with an “antisemitism” of sorts.

What is Proust’s view like, how does he see his characters?

He is merciless. He is direct, realist. Some characters are cruel, but this cruelty can result from a few descriptions about the French society and is always counteracted by the positive part. Merciless, he is. The decadence of the last volume is the relentless passage of time that destroys everything. The last dance of de Guermantes opens up the door and meets the devastating result of the passage of time.

From the religious viewpoint, his religion is art.

It is said that he was a mystic. I believe he was not religious, neither Catholic nor Jewish but he was aware of religions. He reads Pascal, the Bible. But his life is art and his salvation is writing and creating a work of art. This is the only thing that allows him to fight against time because, in the end, will remain.

When does Proust decide to become a writer?

When he was young, he had a vocation to write. He searches for his way and, deep inside, his life is a search of this way, he searches for it through authors he reads and the critics. He tries to do literary criticism, writes pastiches and the novel Jean Santeuil, a primal version and very incomplete of In Search. Was he a snob? He was living in a time when there is a shift in society, aristocracy disappears and the middle class breaks in, another great Proustian symmetry that culminates when the narrator goes back to Paris, after staying in a health centre. The princess de Guermantes invites him to her salon. There he finds again other characters from In Search. Self-promotion and decadences, the passage of time dissolves everything.

Is he a ‘voyeur’?

Proust is a voyeur. Let’s go back to the two voices, dissociated: Marcel and the “I” narrator, a voyeur who is not presented and nobody knows who he is. It is an ambiguous character with an extraordinary capacity to analyze people and social situations, and analyses it with an extraordinary sharpness. He is a voyeur not only of sinful scenes but also of society. He scrutinizes everything, and the result is great literature.

There is a moment between ‘Jean Santeuil’ and ‘In Search’ in which Proust gains a special insight into human nature…

Young Marcel Proust finds his way in the shadows and searches for his way. I think Proust is Proust whenever he invents the character of the narrator. The narrator —he says— explains and says “I”. The narrator who says “I” and is not always “I”. When he meets the narrator, he finds the key to writing a novel. This is the solution that allows him to enter and build the novel. And, I believe, this happens when he finishes Jean Santeuil and realizes that this does not work. He needed to discover the tone and the structure. Proust finds the tone when he becomes aware that another narrator can well exist. And, then, these two voices will lead the novel.

If we read ‘In Search of Lost Time’, do we find the keys to understand the current world?

Proust is contemporary when he criticizes society and its changes, and these changes are thought in one direction but often trigger other changes, in a sense that can even be the opposite. This is an unchangeable lesson in Proust’s work, for the last century and the present century. Time lost, time recovered. When you read Proust, and see how a social class supersedes another, is this not the indirect portrait of a society like ours?