It all started with an ensaimada. Miró took it to Picasso in Paris at the request of the Malaga painter’s mother, taking advantage of the fact that he was traveling to the French capital to organize his first solo exhibition. This is how the two artists met in 1920, beginning a friendship that would last until Picasso’s death. The young Miró found in this message the way to approach a figure that had fascinated him a few years earlier when a ballet with his scenography was premiered at the Liceu, marking a transgressive and free path to follow in his incipient artistic development.

This is the starting point of Miró-Picasso, the great exhibition organized by the Picasso Museum and the Joan Miró Foundation to pay tribute to them, coinciding with the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Picasso’s death. The exhibition is not divided by parts between the two museums, but merged to answer the question that the four curators, Margarida Cortadella, Elena Llorens, Teresa Montaner and Sònia Villegas, asked themselves when they were commissioned five years ago the “grandiose challenge” of facing two artists who marked the history of art in the 20th century and had such opposite personalities and markedly different languages.

“Much has been written about them, but we wanted to know what their friendship meant. This is the thread that has helped us to underpin the structure of the exhibition,” explains Llorens. The exhibition, which can be seen until February 25, does not seek a formal approach to his works, nor does it follow a chronological order, but “makes a raid through the history of this friendship”, defines Cortadella. It starts with their first meeting in Paris and goes up to Picasso’s death, detecting the chapters that marked their relationship over more than 50 years, such as surrealism and wars, but also other disciplines they approached, among them, writing and ceramics.

It is not only an essential exhibition because of its magnitude, bringing together more than 300 works by the two artists, many of them never seen in Barcelona, but also because it is the first time that the two Barcelona museums have exchanged pieces. The complicity that both artists had is thus revived, causing the treasures of each collection to change location for a few months, with Las Meninas ( 1957) moving from the Picasso Museum to the Fundació Joan Miró and The Morning Star ( 1940) making the reverse journey, from Montjuïc to Montcada Street.

“It’s a dream come true. It would be a success if we had only exchanged works with the Picasso Museum, but we have brought pieces from more than 35 institutions and public and private collections,” sums up the director of the Fundació Joan Miró, Marko Daniel. “The idea is not new, Picasso and Miró have crossed paths in many exhibitions,” says the director of the Picasso Museum, Emmanuel Guigon. “The merit lies in the enormous effort behind it,” Daniel continues, “this exhibition is only possible in Barcelona, other major cultural capitals would have a harder time because there is no other city that brings together so many works by both of them.” That is why the director of the Joan Miró Foundation insists that it is a unique opportunity to get close to Miró and Picasso and that it will not be easily repeated: “At least, not in my lifetime”.

Daniel’s warning is not in vain. The Three Dancers can be seen for the first time at the Joan Miró Foundation. (1925), on loan from the Tate Gallery, a work with which Picasso puts an end to his classicism and opens a new stage by portraying a violent history through the distortion of forms and chromatism, finding in the dancers, as well as in the bathers, a field in which to experiment and question the established. It was also for Miró, although his approach was more synthetic but equally charged with eroticism.

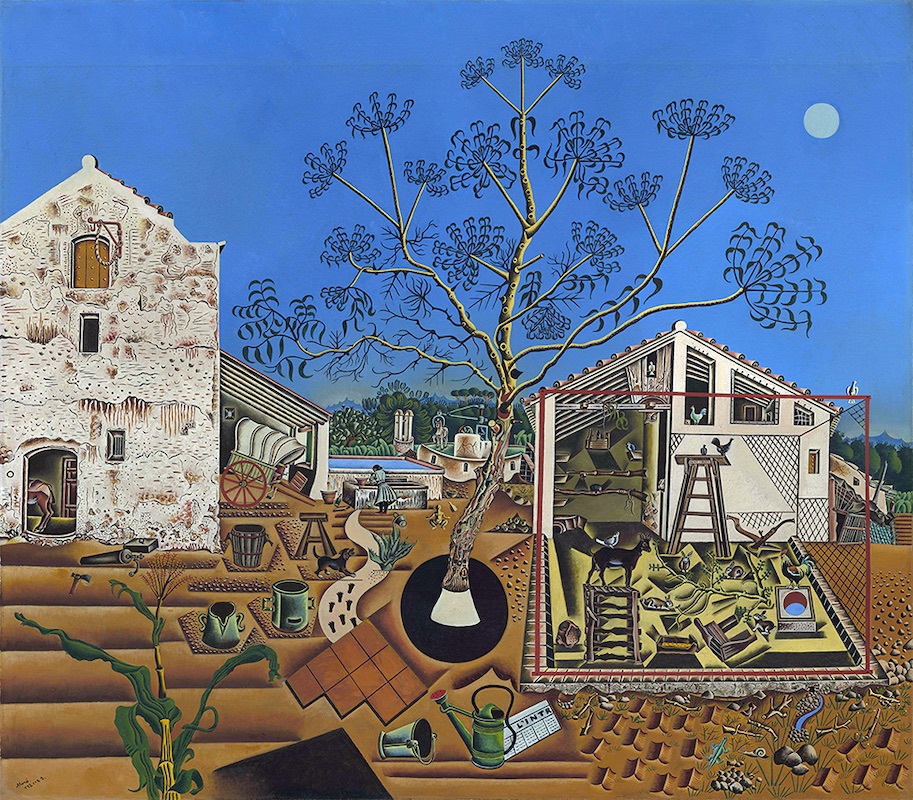

Also unpublished is Miró’s Self-Portrait (1919), which welcomes visitors to the Picasso Museum, very close to another jewel that has traveled to Barcelona, La masía ( 1921-1922), a work that already contains all the elements that the Barcelona painter would exploit over the years. It also has the honor of having fascinated Ernest Hemingway, so it comes from the National Gallery in Washington DC, where it was loaned by the writer’s widow.

Miró left a record of the great friendship that inspects the exhibition on multiple occasions, even being critical of Picasso, for issues such as his excessive production. One of these samples, not always negative, can be seen in El caballo, la pipa y la flor roja ( 1920), where an open book appears in which he reproduces a drawing by Picasso. Also in other later works, such as Woman, Bird, Star. Homenatge a Pablo Picasso (1966-1973) or the logo of the centenary of Pablo Picasso (1980).

Strolling through the Picasso Museum and the Joan Miró Foundation, one often thinks he is looking at a Picasso painting or recognizes one of its forms, and the chop next to it reveals that it is a Miró. Their personal relationship was also artistic, even symbiotic, as can be seen when Picasso’s Great Nude in a Red Armchair (1929) and Miró’s Flame in Space and Naked Woman (1932) come face to face. As if that were not enough, the Catalan painter had a picture of Picasso in all his workshops, proof that he had a profound influence on him, even though they were very different. Both were guided by the same spirit of freedom and transgression to explore the limits of painting.

Picasso was more reserved in showing the admiration he felt for Miró. However, the evidence that reveals his esteem for the Catalan painter is loaded with strength. The Malaga-born painter kept two of his works in his personal collection throughout his life. One is the Self-Portrait, acquired shortly after meeting him thanks to an ensaimada. In fact, in Miró’s first exhibition in Paris, a year after meeting Picasso, it was already stated that he owned it. The second work he acquired was Portrait of a Spanish dancer (1921), an oil painting that takes as its starting point a photograph of the singer Conchita Pérez, remaining faithful to her image but with a clear style of his own.

There is a third work by Miró that Picasso ended up keeping. It would be another tribute to him and, in this case, it was published in La Vanguardia on the occasion of his 90th birthday in 1971. Miró gave it to him as a gift and he placed it in his living room, “among all the things he cherished”, as the Barcelona-born artist later said. After the death of the Malagueño, he was lost track of for many years and his whereabouts were unknown. After much searching, it was found in a private collection outside Spain and can now be seen at the Joan Miró Foundation. This is the end of this never-ending exhibition that vindicates the cultural power of Barcelona with two of its most universal figures.