[dropcap letter=”I”]

f Dogville, the film with which Lars von Trier disconcerted the world once more (after Breaking the waves, The idiots or Dancer in the Dark but before Antichrist or Melancholia), meant a narrative tour de force, developing stories in counterpoint over the squares of a playboard -a maximally abstract reality with the common denominator of the suffering protagonist, Grace- in the theatre version by Sílvia Munt and Pau Miró we find, together with the scenario, audio-visual resources that cinematically delocalize the plot in outdoor landscapes, reversing the logic of the Danish creator in an impeccable way. Because the sense of drama is maintained in the most extreme sense, the one that sharpens urgent questions -already in the middle of the last century- and that postmodernity has not completely concealed: what is the meaning of the word Humanism? Does it possess an intrinsic value, does it refer to some principle of universal respect? And, without a doubt, the most arduous issue: if so, how to practice it without falling in the prioritization of a particular interest?

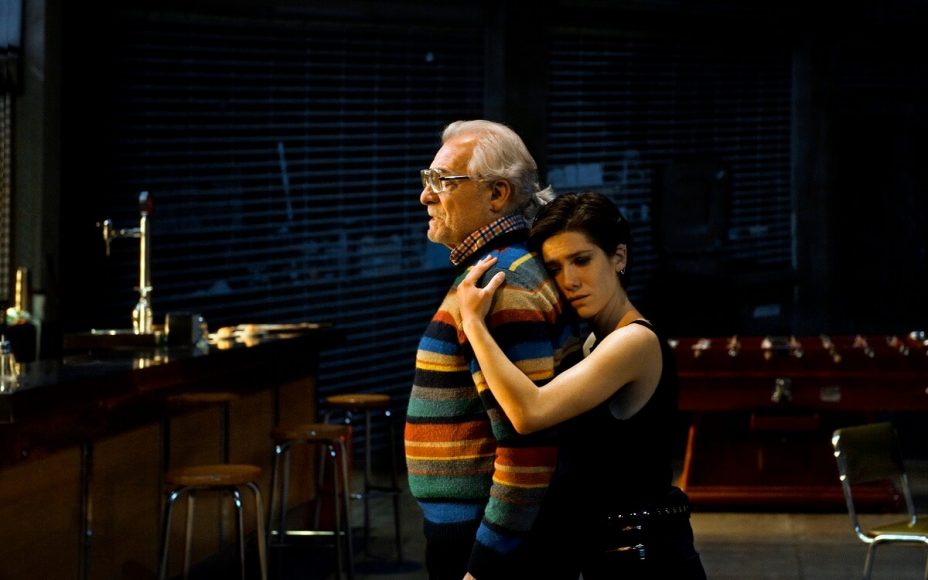

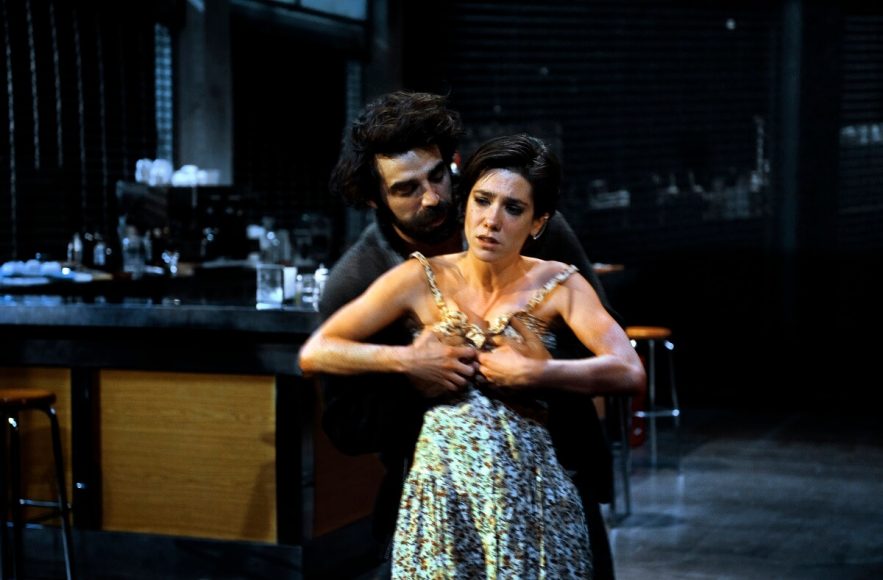

Virginia (Bruna Cusí) flees from a powerful man and seeks shelter in the first place she finds in that “town like any other” -properly specifies the subtitle of the Teatre Lliure version- called Dogville. Just like anywhere else, the bar is the meeting place, the space of confluence of different characters, who come to find distraction. Beyond the passages filmed outdoors and those captured by a fixed camera installed in the limit of the premises in the manner of security cameras -showing what happens inside / outside- everything happens in the different rooms of that popular place. There, Virginia will meet, among others, the idealist and enlightened Max (David Verdaguer), the irate village teacher (Auréa Márquez) and her young and tyrant offspring. Also, the husband and father (Josep Julien), that the woman recognizes somehow primitive. Not forgetting an old man, who hides his blindness (Lluis Marco) and makes believe he see things just as they are, stubbornly inspired by his belief.

Being unconditionally helped by someone who asks for nothing, that in her transparency acts only as a mirror, the imperfections, insecurities, desires, traumas of the characters will emerge irremediably.

The characters are initially suspicious towards the protagonist, while she tries to gain her trust by offering a selfless collaboration. Using a falsely objective resource such as the voice-over, Lars von Trier had enjoyed, with the precision of a surgeon, in the externalization of the repressed instincts, entrenched or socially accepted in all of them. They emerge in the film as a black smoke in front of Grace’s charitable action, a female character obviously related to those of Breaking the Waves and Dancer in the Dark. The theatrical version of Dogville cannot offer that same degree of detail, but it emphasizes the false naturalness of the speeches of those who do not really tolerate the consequences of the pact. Because in the trance of being helped unconditionally by someone who does not ask for anything -which in his virginal transparency acts only as a mirror- the characters’ imperfections, insecurities, desires, traumas will emerge irremediably.

CYNICISM, AN IMPASIBLE CONCERN FOR THE HUMAN

There are many passages that would be worth quoting, such as when the character of Gloria (a wonderful Anna Güell) states, lapidary: “we are very good people, especially if you have a bad memory”. Likewise, and perhaps above all, one of the statements that closes the piece deserves to be highlighted -“fear justifies everything”- to the extent that it illustrates the cynicism that predominates in that microcosm. Cynicism was defined by Peter Sloterdijk in his first great work as a “falsely enlightened conscience”, a form of lucidity that renounces truth while not hesitating to impose its own criterion as universal. The sentence of Gloria is, thus, unequivocal: with the moral notions “fresh” in mind there would be no way to agree on the goodness of the inhabitants… Something different happens when strange and uncontrollable factors – fear, for example – “weaken” the memory of what is universally good. The sentence of the blind person seems to paraphrase, somehow, the diagnosis of the character of Albert Camus’ La chute, a former judge that recognizes the human propensity to blame the entire humanity in order to save oneself.

Even Max, who boasts of openness and a clean look -having been the first to put himself in the place of the persecuted foreigner- will rush into moral ambiguity because of the uncertainties derived from their affective attachment, which raises a question uncomfortable: is it really possible to give fair treatment -that is, disinterested- to the one whose love is asked for, intuiting that it is not fully corresponded? Immanuel Kant spoke of the “obstacles of human nature” to refer precisely the series of empirical conditioners (interests, inclinations, and of course emotions) that tend to affect our moral praxis, and that would have to be transcended in the truly legitimate act, according to principles of universal validity. Although it may seem paradoxical, the contradiction appears in an especially flagrant way in the one who vehemently defends the principles of enlightenment, principles that affirm the equality and inalienable freedom of all human beings.

Well, as a matter of fact, anyone who upholds principles or wants to defend values is bound to contradict himself more than the cynic, who becomes strong from the self-satisfied confession of his moral ubiquity, a little like the Karamazov saying (“if God does not exist, everything is allowed”). In Dogville it is widely spread the secret that modernity usually obviated, or rather hid under the carpet of that Kantian expression: that the tendency of man -as Thomas Hobbes had already warned in a less aseptic way- is not that of protecting the helpless, but using different means -amongst them, obviously, the force- to prosper according to one’s instincts or most “reasonable” desires, which does not exclude taking advantage of the others’ goodness. Homo homini lupus. The animal chosen in Trier’s fiction is the mammal considered most loyal to man, and therefore the one that most intensely is in the position of suffering because of his abuse, just like it is referred by the colloquialism “a dog’s life”. An expression that is employed to illustrate the kind of existence that is victim of clearly unjustifiable sufferings, such as those experienced by the protagonist of Dogville.

Even if the spectator which may be familiarized with the film will miss Trier’s stark and obscene closeness -as well as that manipulative voice-over- a comparable point of imposture is perceived in the voices of the theatrical characters, which articulate a choral truth and yet deeply anti-humanist

Lars von Trier’s Grace (Nicole Kidman) chooses to assume quietly every humiliation, while certainly in the version of Sílvia Munt and Pau Miró she, “Virginia”, appears to be, despite the reminiscence to her original purity, more vehement and rebellious. Even if the viewer familiar with the film may find that nuances are lacking in the version of the Teatre Lliure -Trier’s stark and obscene proximity, as well as that fascinating and manipulative voice-over a comparable imposture is perceived in the voices of the characters, who with outstanding performances articulate a choral and yet deeply anti-humanist truth. Intermittently, as the plot progresses, they address separate speeches: private interviews facing the public, as if it were a documentary -a procedure, by the way, that Lars von Trier himself used to shoot The Idiots– and in which they talk retrospectively about the turbulent imprint left by the foreigner. A resource that, however, in any way we could find in the film version, for obvious reasons for those who know it and that we will remember shortly.

ABOUT THE SAINT AND THE SINNER

Before, it is almost obligatory to mention Temps Salvatge -a work by Josep Maria Miró, programmed last season at the Teatre Nacional de Catalunya- due to the similar recreation of a community gripped by fear in the presence of someone strange, and in which a young woman plays the fundamental role. And this despite the fact that the protagonists, who in both cases orchestrate and condition the affections of the characters, around them, would seem antithetical. One is close to the role of the saint, given herself to all without conditions -something very noticeable in Trier’s heroine, as we said- while the other is the nonconformist, who provokes and recklessly seizes life’s most radical experiences, while she exploits the hypocrisy of adults. In fact, Virginia can be placed in between the two of them, since she starts being a rebel and never loses completely that exalted and even aggressive mood, which applies against herself. The profile of the original character (Grace) is definitely closer to that of Joan of Arc, whose martyrdom Lars von Trier obviously met through the version of his admired Carl T. Dreyer. The suffering of those feminine characters is the price they pay for having provoked the emergence of what could not be said or heard, for having behaved as mirrors that reflect the most ugly, unbearable inner reality.

If the aesthetic experience of injustice slaps the spectator’s face, that’s because it reminds that in real life, too, the returns to any “Dogville” -with variations, of course- take place. And unlike what happens in fiction, not always relations of submission know some kind of purpose or resolution. The capital discrepancy between the work of Trier and the interesting version of Munt and Miró lies, precisely, in their different endings. While in the film it is produced, with the arrival of the Father (the mysterious man from whom Grace fled, in the beginning) a dramatic turn that completely changes the order of things of the place referred to as Dogville, in the theatrical version that “town like any other” follows its path without substantially modifying the dynamics, in spite of the intrusion of Virginia and the death of Max, the most similar to an innocent being in the city of the dog. The moviegoers will remember, on the other hand, what happens to Grace after all the vexations inflicted by the helped ones.

The spectator breathes, relieved: justice has been done, after all. But the relief, the emotional discharge that brings this falsely redemptive ending shows a degree of extreme perversion

And what happens, is that she endures an epiphany: before the offer of her father -not metaphorical at all- consisting of “burning the town”, as it this is remembered in the Teatre Lliure version, she realizes that definitely, injustice exists, and that it cannot be tolerated; that in some way to assume it in the flesh, to respect it, makes possible its perpetuation and turns the victim into an accomplice. The almighty father, orthodox gangster -father hated / loved, according to the Freudian tradition- will eradicate all life form in the town with fire and bullets, saving only the dog. The spectator breathes, relieved: justice has been done, after all. But the relief, the emotional discharge that brings this falsely redemptive ending shows a degree of extreme perversion, perpetrated by the disturbing alchemist that has proven to be so many times Lars von Trier.

The spectator goes from suffering with Grace -that idea of empathy inherent in Christian love, charitable, which accepts to lower oneself and carry the burden of the other- to feel, like Grace herself, convinced of the significance of a mass murder. A wild change of perspective that challenges the viewer / accomplice and shakes him from the other side of the screen, in a manner only comparable to the one provoked by Stanley Kubrick, decades ago, with A Clockwork Orange. After a first part of debauchery, with repulsive examples of the so-called “ultraviolence”, in the second part of the film the criminal, in the process of reformation, becomes the victim of infrahuman experiments and also victim of his old gang mates. The viewer can understand that he -the character named Alex- has indeed deserved it, or the viewer can empathize and feel sorry for his condition. In both cases he / she is affected by unexpected emotions and forced to revise his moral criteria, however little he may be aware.

TIMELESS AND UBIQUITOUS DIALECTICS

After her stay in Dogville Grace seems to have learned a lesson about moral distinctions, who knows if traumatically. And yet her will to lecture, her desire to bring the true meaning of good – freedom and justice- to the lives of men and women plays a trick on her in Manderlay -second part of Trier’s trilogy- when, victim of her anger, she ends up whipping sadistically the desired but cynical slave, which abounds in the inherent problematic of humanism, that Max suffers in Dogville Max (Tom, in the movie). Both films stage with the minimum of narrative resources and maximizing the expressions of the actors -according to the theatrical mode but with the filmic possibilities, thanks to the variety of shots and montage- the critical discourse that some 20th century thinkers conceived against the too much optimistic presumptions of Enlightenment.

In the context of WWII, Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer stated in their Dialectic of Enlightenment that the project to liberate and improve mankind by relying on Reason had clearly failed, not being credible anymore except from a faith or a blind trust, similar to the one that had brought inequalities and had not been able to avoid the armed disaster. Already Nietzsche had denounced the pragmatic aspect of reason, inevitably placed at the service of particular interests, and therefore a servant of the instinctive, as Sade knew, to whom Adorno and Horkheimer also refer in order to sharpen their mistrust in an entirely rational form of salvation. In fact, the authors of that classic work consider that the merciless doctrines of Sade and Nietzsche are more “merciful” than the bourgeois morality for having proclaimed “the identity of reason and dominion”, that is, for having anticipated the appropriation of the meaning of reality through a type of instrumental reason, which basically thinks in terms of efficiency and profit.

A pragmatically oriented thought that, from a distance and justified suspicion, is close to that of Martin Heidegger denominates in his communication Serenity “calculating thought”. In the late forties, he also tried to redefine the meaning of Humanism in conversation with Jean Beaufret, taking into account the critique of technique and its application to human matters. In the 1966 interview granted for the Spiegel, Heidegger affirms that where man lives “is no longer the earth”, after referring to the picture of the planet from the Moon (a black and white image, not the most popular one, coloured, taken in December 1968). The uprooting from the surrounding world, the muddle of interpersonal relationships and of the individual himself constitutes the unhospitable reality (Das Unheimliche is the term employed by Heidegger, translated as “the sinister”) that Dogville stages. In addition to the marvellous interventions in counterpoint of the actors, the Teatre Lliure version is undoubtedly interesting -as it has been said- to show the timeless and ubiquitous nature of this fable, which can happen “in a town like any other”.

The risk of remaining merrily installed in criticism, not only in an aprioristic idea of truth or justice, is also warned by Adorno in Minima moralia: “for that individual who shows unconformity there is the danger that he / she considers himself / herself better than others and uses his /her criticism of society as an ideology at the service of his / her private interest.

That precision neutralizes any temptation to believe (or want) to identify a concrete and exclusive context -as Lars von Trier himself pointed out in the title of his trilogy: USA- Land of Opportunities– and to save oneself from the possibility of corruption or alienation from the world or from oneself. The risk of remaining merrily installed in criticism, not only in an aprioristic idea of truth or justice -as happens to Manderlay’s Grace- is also warned by Adorno close in time to the writing of the work conceived together with Horkheimer. In Minima moralia, a compendium of brief essays that already offer a glimpse of his philosophy and his negative aesthetics, points out: “for that individual who shows unconformity there is the danger that he / she considers him / herself better than others and uses his /her criticism of society as an ideology at the service of his / her private interest. While trying to make his / her own existence a pale image of the righteous existence he / she should always keep in mind that pallor and know how little such an image represents right living”. Indeed, in the enlightened pretension -as much as in critical thinking- those “obstacles of human nature” that undermine the best intentions can infiltrate.

To perceive inhumanity as underlying the human, in such an intimate and distant proximity, may feel unbearable. But, possibly, only from that tenebrous reverse, keeping it in mind and not obstructing its unpleasant reality, may it be possible to value the exceptional nature of the human being in its just measure -i. e., beyond all measure. Let’s conclude with a second quote from Minima moralia, insofar as it ratifies the critical scenario – the need for criticism of criticism, or a form of re-illustration that circumvents cynicism – opening itself, nevertheless, to a possible utility of thought and of the work of art that seeks to encourage reflection, rather than to please or comfort: “there is no beauty or consolation except for the look that, addressing horror, faces it and, in the unalienated awareness of negativity, affirms the possibility of the best”.