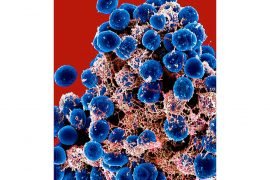

Lung cancer with tumors that present a specific epigenetic mark,...

In Stuttgart there are two imposing museums for two leading...

Graduated in Biological Sciences from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona...

The patient will wear a bracelet with a tag connected...

The Sant Martí facility wins the award shortly after its...

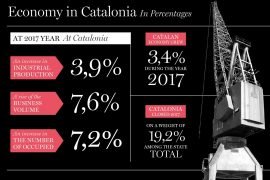

The Catalan economy grew 3.4% in 2017 according to estimates...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

Alzheimer's is, like the human brain itself, a mystery to...

We are beginning to take in that it is possible...

What happens when a person comes in contact with the...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”B”]

arcelona-Athens flight with Aegean Airlines. Cloudy weather, overcast sky. Between Cape Sounion and Piraeus, we are flying over a choppy sea in a range of greys: pearl grey, silver grey, anthracite black-grey. On the indistinct horizon we can glimpse the silhouette of Aegina, the island where Plato was born…

Nephos – fog – is Athens’ smog. Nowadays, Athens is the city with the highest levels of air pollution in Europe. With the recession, which proved such a heavy blow to the country, the capital, which is always humid, has become a filthy city, extremely filthy. Like the lower depths of Genoa or Naples, the port activity seems to have tinged everything with fluids and excrement.

We take the underground, which also runs aboveground along some stretches. They are visual, artistic, the Greeks. Unlike London, for example, where looking at people is poorly viewed, here people look and are looked at without qualms. I like that. “Du fond des âges monte la nécessité irreprensible de voir” (Paul Eluard).

Atop a bus, I peer at the lad in front of me, his lips pierced and lost in his headphones. He quickly points when we pass in front of a church. Then the Orthodox “father” smiles, his long hair in a ponytail, enveloped in his soutane now the colour of a fly’s wing. I imagine him within the iconostasis, officiating with his back to the audience as incense burns and the choir of men with their carefully coiffed hair sings.

We take the underground, which also runs aboveground along some stretches. They are visual, artistic, the Greeks. Unlike London, for example, where looking at people is poorly viewed, here people look and are looked at without qualms. I like that.

These Byzantine Christians cross themselves three times, kiss icons, touch them, revere them. It is a kind of exaggeration that must come from the depths of history, from the terrible struggles of the iconoclasts – who believed it was inappropriate to represent the Deity, who for them is pure Idea. I mean that these signs of adoration may come from the reaction against those purists. And this strong attachment to imagery may stem from that.

Reflecting a deeply-rooted sense of representation, the images from the iconography of Orthodox Christianity encompass all dogmas and beliefs that are sensitive to the sight. But they are only painted images. Not sculpted. Even today carvings are forbidden. In fact, they were not introduced into the Roman church until the 10th century.

The Eastern schism – or Western, depending on how you look at it – is the key: it dates from 1054. A century and a half later, the Crusaders sacked Constantinople: they destroyed the iconostasis of Hagia Sofia, seated a prostitute in the patriarch’s chair, smelted the treasure of the schismatic church… It was a civil war between Christians.

Rome had fallen to the barbarians in 410. But the Eastern Roman Empire lasted until 1453, when the Turks entered Byzantium (or Constantinople, now Istanbul). What still lingers today in the Greeks’ memory is the awareness of having been the Byzantine Empire, perhaps more than Athenian democracy…

We climb to the Parthenon among the eager throngs of tourists. However, the spectacle rewards all the bother: the elevation provides us with a clean view of horizons that are unusually haze-free today, totally scrubbed of any obstacles. In a sweeping panoramic scene, Athens reveals its entire self today, bathed in light, spreading out around the holy mountain under an azure sky.

On the southern flank of the Acropolis is the theatre of the sanctuary devoted to Dionysus or Pan, the god of wine, frolic and dance. He was the pastoral god of Arcadia, the most popular god in classical Greece. Here, in this open space, perhaps a roofless temple, the bacchanalias were held, the festivals announcing springtime with maenads, satyrs and Silenis. This is where the tragedies and comedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes premiered. Which served as a kind of secularised religion.

At first, disguised as forest animals, as serpents or birds, the actors just officiated in holy rites, which can be associated with worship of the plant world. Later the chiding choir was smoothly slipped in.

The Apollonian Arístides Maillol considered the Parthenon “humanity’s most beautiful work”, which “far and away seems to be the pearl of Greece”. “Nothing has such beautiful colours as the Acropolis, all in a golden, pale, mauve tone”, he wrote in his travel notebook

The theatre, as the school for human learning, was born from this dialogue between that which is unformed and that which takes shape, from the replacement of savage community by rule-bound society. All Greek culture, and all Western culture, comes from this duality between the raucousness of Dionysus and the wisdom of Apollo.

The Apollonian Arístides Maillol considered the Parthenon “humanity’s most beautiful work”, which “far and away seems to be the pearl of Greece”. “Nothing has such beautiful colours as the Acropolis, all in a golden, pale, mauve tone”, he wrote in his travel notebook.

The great sculptor from Roussillon travelled to Greece in 1908, looking for “an outdoor statue” (which he found in Delphos), since its natural environs is outside, in the open air. “What a compulsion to put everything inside museums, where you get bored, where you see it badly, where you are watched over by guards…”

Since there is no better spectacle than passers-by, we have lunch on the street, under the Acropolis, in the Plaka: the traditional Greek salad – with olives, capers and feta cheese – retsina wine, pork souvlaki and a slice of watermelon for dessert.

Afterwards, a Turkish coffee (which, by the way, is called “Greek” here, heavy with grounds on the bottom, served, as it should be, with a glass of cool water. And music, the popular, perennially tender music of Manos Hatzidakis.

[dropcap letter=”B”]

arcelona-Athens flight with Aegean Airlines. Cloudy weather, overcast sky. Between Cape Sounion and Piraeus, we are flying over a choppy sea in a range of greys: pearl grey, silver grey, anthracite black-grey. On the indistinct horizon we can glimpse the silhouette of Aegina, the island where Plato was born…

Nephos – fog – is Athens’ smog. Nowadays, Athens is the city with the highest levels of air pollution in Europe. With the recession, which proved such a heavy blow to the country, the capital, which is always humid, has become a filthy city, extremely filthy. Like the lower depths of Genoa or Naples, the port activity seems to have tinged everything with fluids and excrement.

We take the underground, which also runs aboveground along some stretches. They are visual, artistic, the Greeks. Unlike London, for example, where looking at people is poorly viewed, here people look and are looked at without qualms. I like that. “Du fond des âges monte la nécessité irreprensible de voir” (Paul Eluard).

Atop a bus, I peer at the lad in front of me, his lips pierced and lost in his headphones. He quickly points when we pass in front of a church. Then the Orthodox “father” smiles, his long hair in a ponytail, enveloped in his soutane now the colour of a fly’s wing. I imagine him within the iconostasis, officiating with his back to the audience as incense burns and the choir of men with their carefully coiffed hair sings.

We take the underground, which also runs aboveground along some stretches. They are visual, artistic, the Greeks. Unlike London, for example, where looking at people is poorly viewed, here people look and are looked at without qualms. I like that.

These Byzantine Christians cross themselves three times, kiss icons, touch them, revere them. It is a kind of exaggeration that must come from the depths of history, from the terrible struggles of the iconoclasts – who believed it was inappropriate to represent the Deity, who for them is pure Idea. I mean that these signs of adoration may come from the reaction against those purists. And this strong attachment to imagery may stem from that.

Reflecting a deeply-rooted sense of representation, the images from the iconography of Orthodox Christianity encompass all dogmas and beliefs that are sensitive to the sight. But they are only painted images. Not sculpted. Even today carvings are forbidden. In fact, they were not introduced into the Roman church until the 10th century.

The Eastern schism – or Western, depending on how you look at it – is the key: it dates from 1054. A century and a half later, the Crusaders sacked Constantinople: they destroyed the iconostasis of Hagia Sofia, seated a prostitute in the patriarch’s chair, smelted the treasure of the schismatic church… It was a civil war between Christians.

Rome had fallen to the barbarians in 410. But the Eastern Roman Empire lasted until 1453, when the Turks entered Byzantium (or Constantinople, now Istanbul). What still lingers today in the Greeks’ memory is the awareness of having been the Byzantine Empire, perhaps more than Athenian democracy…

We climb to the Parthenon among the eager throngs of tourists. However, the spectacle rewards all the bother: the elevation provides us with a clean view of horizons that are unusually haze-free today, totally scrubbed of any obstacles. In a sweeping panoramic scene, Athens reveals its entire self today, bathed in light, spreading out around the holy mountain under an azure sky.

On the southern flank of the Acropolis is the theatre of the sanctuary devoted to Dionysus or Pan, the god of wine, frolic and dance. He was the pastoral god of Arcadia, the most popular god in classical Greece. Here, in this open space, perhaps a roofless temple, the bacchanalias were held, the festivals announcing springtime with maenads, satyrs and Silenis. This is where the tragedies and comedies of Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and Aristophanes premiered. Which served as a kind of secularised religion.

At first, disguised as forest animals, as serpents or birds, the actors just officiated in holy rites, which can be associated with worship of the plant world. Later the chiding choir was smoothly slipped in.

The Apollonian Arístides Maillol considered the Parthenon “humanity’s most beautiful work”, which “far and away seems to be the pearl of Greece”. “Nothing has such beautiful colours as the Acropolis, all in a golden, pale, mauve tone”, he wrote in his travel notebook

The theatre, as the school for human learning, was born from this dialogue between that which is unformed and that which takes shape, from the replacement of savage community by rule-bound society. All Greek culture, and all Western culture, comes from this duality between the raucousness of Dionysus and the wisdom of Apollo.

The Apollonian Arístides Maillol considered the Parthenon “humanity’s most beautiful work”, which “far and away seems to be the pearl of Greece”. “Nothing has such beautiful colours as the Acropolis, all in a golden, pale, mauve tone”, he wrote in his travel notebook.

The great sculptor from Roussillon travelled to Greece in 1908, looking for “an outdoor statue” (which he found in Delphos), since its natural environs is outside, in the open air. “What a compulsion to put everything inside museums, where you get bored, where you see it badly, where you are watched over by guards…”

Since there is no better spectacle than passers-by, we have lunch on the street, under the Acropolis, in the Plaka: the traditional Greek salad – with olives, capers and feta cheese – retsina wine, pork souvlaki and a slice of watermelon for dessert.

Afterwards, a Turkish coffee (which, by the way, is called “Greek” here, heavy with grounds on the bottom, served, as it should be, with a glass of cool water. And music, the popular, perennially tender music of Manos Hatzidakis.