[dropcap letter=”A”]

n eleven-year-old boy who works in a factory with his father falls into a tub full of boiling dye and comes out with very severe burns on his legs. To heal it and avoid amputation, donor skin-grafts are needed. Thirty-five workers, including two sons of the owner, volunteer to let their skin be removed without anesthesia and to save the little José Caparrós. This sad story, which happened on February 23rd, 1905, illustrates the character of the worker-inhabitants of Colonia Güell, one of those towns created out of nothing around a factory at the end of the 19th century, like so many others that emerged in that time on the margins of the Llobregat river, or the Ter. A place where solidarity arose in difficult times, but also a sealed world where it could be difficult to get away from the foreman when he harassed the worker and who, refusing to repair the loom, could leave her without means of living if she did not give him what he wanted. And a world where child exploitation -even if it was not allowed, officially- was common and somehow accepted.

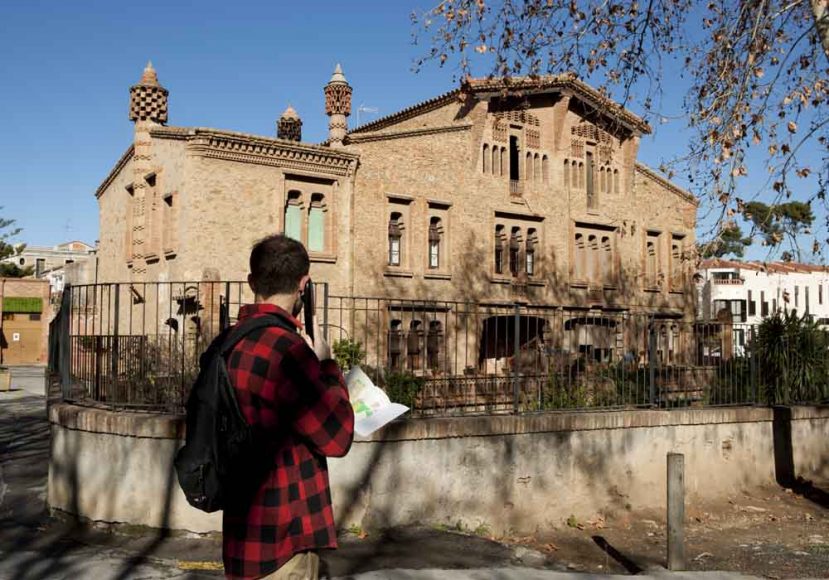

Visiting the Colonia Güell today is to get to know one of the best testimonies of an era that is not that far away -the factory closed in 1973-, even if it sounds like it belongs to another time. Located just 15 kilometers from Barcelona, in the municipality of Santa Coloma de Cervelló, it is a redoubt of six hectares that, more than a century later, still amazes for its urban quality, which contrasts with a much denser metropolitan environment, and by the mark that left Antoni Gaudí.

Declared an Asset of Cultural Interest, it can be visited since 2002, when it was opened to the public as a tourist attraction. This year it is commemorated the Güell Year, being the death centenary of this capital figure of Barcelona and Catalonia, that lived in the last third of 19th century and early 20th. The number of visitors to the Colony increases continuously, to reach 70,000 per year. An amount, that is still far from the overcrowding suffered by other tourist environments, especially those linked to Gaudí, and which allows a very quiet and relaxed visit.

The industrial complex occupies the land of the old estate Can Soler de la Torre in Santa Coloma de Cervelló. Founded by Eusebi Güell in 1890, the colony, one of the last ones that were created in Catalonia, was a great business project and a sociological experiment of the time, since it sought to keep the workers away from the social conflict of the big city. “The colony was isolated from outside influences and the director was head of the factory, but he also acted as if he was the mayor,” explains Montse García, head of the Interpretation Center of Colonia Güell. The three cornerstones in the colony, where nearly 1,400 people lived and worked, were: education, effort or work, and religion, according to the principles of the most paternalistic social Catholicism. People were born and lived their lives there, with no need to leave. This social order was only shaken by the Civil War, when the factory was collectivized, and when strikes arrived, initiated by women, already in the sixties.

The workers, therefore, did not enjoy luxuries, but in return they did not lack anything, as long as they did not question the owner and the established order. Thus, the Colonia Güell has very wide streets perfectly urbanized and very spacious houses, about 120 square meters on average, with patio and garden, as well as all the necessary services such as doctor, school, an athenaeum and theater, among others. The visitor can check, walking through the five streets of the colony, how this space, fully inhabited today as a normal village, has become a good urban model that differentiates it from the rest of industrial colonies in Catalonia, such as Vidal’s or Soldevila’s, also on the margins of the Llobregat river.

“La Colonia”, as its inhabitants call it, has preserved to this day the quiet village atmosphere, but having buildings where the modernist architectural mark of the time -developed by the leading architects, such as Joan Rubió Bellver and Francisco Berenguer- is found. And in the middle of this industrial heritage, based on one of the pillars of Güell’s doctrine, emerges the church, declared World Heritage Site by Unesco, the work of the greatest master of Catalan modernism: Antoni Gaudí.

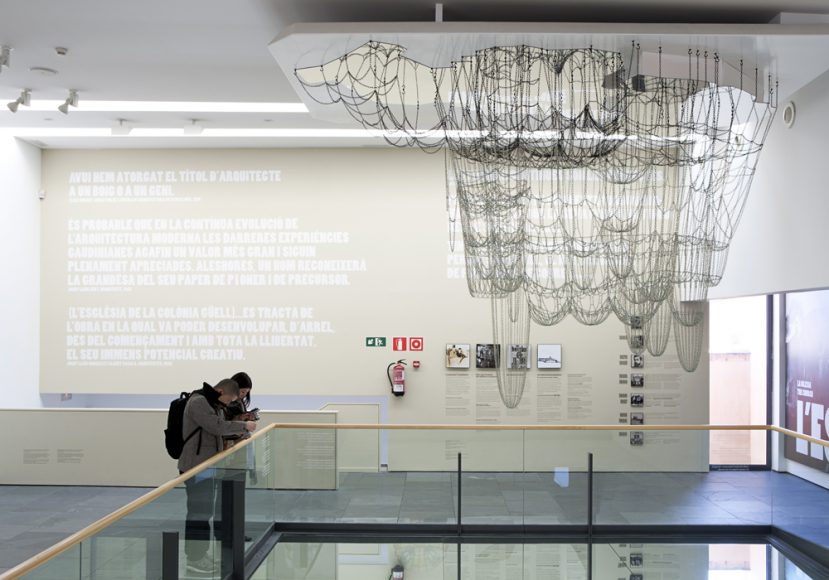

However, just like the Sagrada Familia, we are talking about an unfinished work. Eusebi Güell commissioned the construction of the temple to his friend Gaudí -with whom he had already collaborated to build the Güell Park and the Palau Güell- with instructions to “do whatever he wanted”, without technical, budgetary or time limitations. The works began in 1908, after an ambitious project which envisaged a church with two naves, lower and upper, topped by lateral towers and a central dome 40 meters high. But, once the patron was dead, Eusebi Güell’s sons informed Gaudí that they would not continue to finance the works, and he abandoned the project.

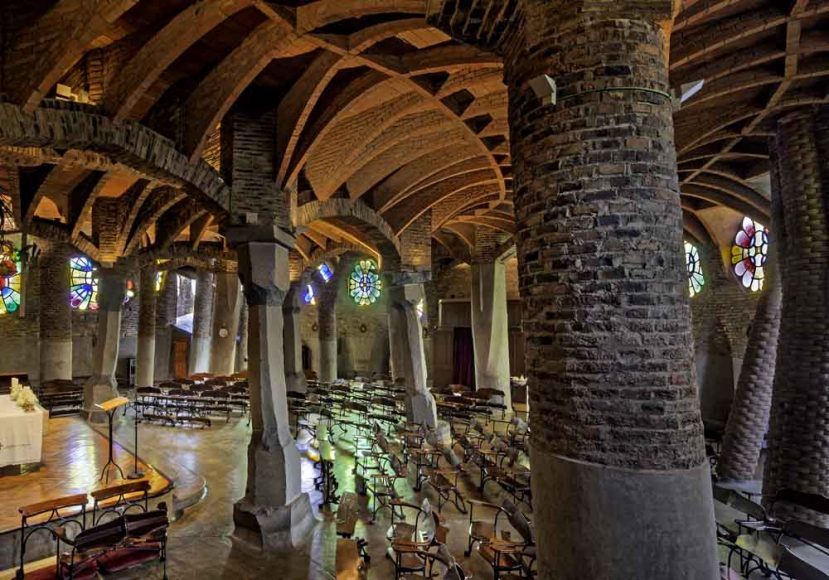

Only the lower nave was completed, known as the Crypt, which continued to function as the Colony’s church to the current date. Despite being unfinished, the church supposes a culminating point in the work of Gaudí, since it includes, for the first time, all his architectonic innovations. In fact, the Crypt was a “test laboratory” for Gaudí, and many of the architectonic solutions that the master experimented there would be applied, later, to the Sagrada Familia. Gaudí was interested in much more than beams and pillars, and also devoted himself to making the church benches by using recycled material such as oak wood from the boxes that packed the machines of the factory and the iron that haul the cotton balls through looms. Furthermore, benches are placed in such a way that everyone who sits can only look forward to the altar, without being distracted by other “details”. The exterior pillars, made by recycling burned bricks, were conceived to match with the pines of the environment.

Gaudí and Güell shared an ideology that clashed with the interests of businessmen of the time. They are described as pioneers of social justice, for their concern for the welfare of workers instead of their exploitation. Certainly, workers spent 12 hours a day in the factory, but they enjoyed medical services, a school where even the children could learn German (the instruction of the girls was more limited), and there was always something to eat at the table. In a time when there was hunger, and illiteracy was common, it is no small achievement.

After the closure of the textile factory of the colony in 1973, the owners sold the houses to their tenants. This has allowed the Colonia Güell to be almost completely inhabited, unlike what happened to other colonies, which after closing the factories have been uninhabited. Of the 800 people currently living, 25 percent are people alien to the Colony who, after buying the house to the first owners or their descendants, keep on enjoying this haven of peace -still in our days- in the middle of the metropolitan area of Barcelona.