“PLANTA is an innovative project. An innovative project in art, an innovative project also in the business world. It emerges from the intersection of the two worlds: the Sorigué group, the business world, and the Sorigué Foundation, art”. This is how Ana Vallés, president of Sorigué and director of the foundation, expresses herself. In PLANTA those elements are integrated: it is an industrial production platform that seeks to be respectful with the environment, turned into a centre for contemporary creation. There are names as relevant as those of Antonio López, Bill Viola, Anselm Kiefer, Anish Kapoor or Juan Muñoz, whose work Double Bind -previously in the turbine hall of the Tate Modern- has adapted perfectly to the space of the Balaguer (Lleida) plant.

“We want, above all, that visitors take questions with them”, explains Ana Vallés. More than lecturing or entertaining, contemporary art plays a sometimes uncomfortable but fundamental role: to stir up prejudices and promote critical thinking.

The Foundation, inaugurated in 1985 by Julio Sorigué and Josefina Blasco, emphasizes the need to make effective the “return to society” by means of support programs for some vulnerable sectors, as well as with educational and cultural activities aimed at the general public. Among them, it is worth mentioning the art collection, a collection started with works of the Catalan Noucentisme -produced from the collection of the Sorigué family- that was enlarged in 2000 with the incorporation of works by contemporary creators, until reaching a figure higher than the 450, selected by a commission of experts, namely José Guirao, Rafa Doctor, Miguel Zugaza, Paloma Esteban, Julio Vaquero, or José Miguel Ullán.

The criteria selection of the works of the collection are perfectly aligned with the programming of exhibitions, which feature creators of maximum relevance in the artistic scene and also others less known, although with an accredited potential. All of them care about issues which are inherent to the human condition, especially stimulating in their artistic expression. “We are want, above all, that visitors take questions with them”, explainsAna Vallés. More than lecturing or entertaining, contemporary art stands out for its involvement, for the performance of a sometimes uncomfortable role, but fundamental to stir up prejudices and promote critical thinking through emotional experiences.

DE/MATERIALISATIONS OF A HASSELBLAD PRIZE

For a long time now, art has quitted illustrating exemplary actions, memorable subjects or singular manifestations of nature, being the aesthetic experience -in itself- the protagonist, instead. By incorporating technologies that allow transcending the traditional gender frontiers, contemporary creations provoke a more intense participation of the spectator. The exhibition that can currently be visited at the Fundació Sorigué de Lleida (until December 30) is a clear example of this. It is an exhibition focused on the work of Óscar Muñoz, who recently -coinciding with the exhibition, in fact- has received the prestigious Hasselblad prize (names as important as Nan Goldin, Boris Mikhaïlov, Cindy Sherman or Henry Cartier-Bresson were awarded in the past).

Despite not being a photographer, Muñoz uses photography to reflect on the ephemeral character of the human being. It should not surprise, therefore, the giving of the award (by the brand of cameras used by the first men on the moon, almost 50 years ago), because what his work transmits, through moving images, is the expiration that is intrinsic in the reality that seeks to be is fixed and reproduced. Precisely the will of stopping time -which photography seems to satisfy- reveals a need inherently rooted in the nature of the human being: being that knows him/herself alive as long as he/she lasts, being conscious also of (from) its natural tendency to stop being.

The fact that Óscar Muñoz’s exhibition is entitled De/materialisations emphasizes the need for that trace that, more or less artistically, human beings tend to project in their time of life, as a manner to transcend it.

The exhibition consists of a series of audio-visual installations that pose a dialectic as old as photography itself, although -in reality- it is already implicit in all forms of art. The primitive gesture of marking and leaving a trace in the prehistoric cavern -perhaps to exorcise nature, tame the elements and make hunting more propitious- supposes a significant activity, which brings together being and non-being. The fact that Óscar Muñoz’s exhibition is entitled De/materialisations emphasizes the need for that trace that, more or less artistically –often hysterically, as evidenced by social networks- human beings tend to project in their time of life, as a manner to transcend it. One of its installations, Sedimentations, illustrates the topic of the flow of lives, sordidly presented by portraits that deform and sneak down the drain, in an anguished spiral, worthy of the film Vertigo (not in vain it was also known by the name of the novel that inspires it, The Living and the Dead).

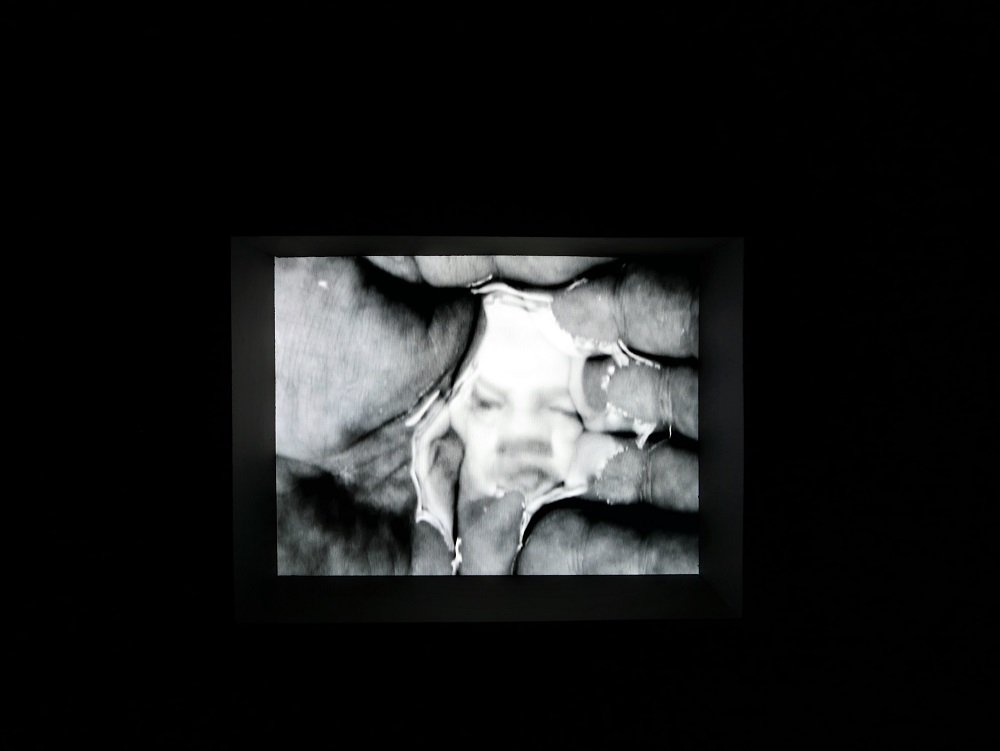

Images of the deceased are shown naturally -beings that, at first, we would believe as alive as we do- those that are lost, irremediably, until they are nothing more than a stain that represents nothing. Because, in fact, those images have never been alive. Gemma Avinyó, Head of Visits at the Sorigué Foundation, alludes to this “longing to be permanent” as a result of another of Óscar Muñoz’s works, specifically that entitled Line of Destiny: in the bowl that forms the hand, a volume of water reflects the changing face of whoever looks at it, alternating recognition and disfigurement. Being-represented and stop-being are correlated with an alarming eloquence: can we be that which we do not seem to be? Questions arise thanks to the aesthetic experience that awakens emotions, and that encourages the search for answers. As neuroscientists have shown, this emotional imprint is the most efficient way to receive and fix knowledge.

Gemma Avinyó recalls the importance of mediation, in the case of contemporary art. She refers to the series of explanations -offered by the Foundation to visitors or groups of students who wish to hear them- that do not sentence or close the issues, but rather suggest personal interpretations. There are many schools that benefit from this service, that also works with the teachers themselves, so that later they can develop activities in which those ideas come to life, having internalized through their own experiences. The spectators of the exhibition become co-participants, composing themselves works in which the question of identity is posed. In the context of the omnipresence of the digital image -shared by all, in our time- the work of Óscar Muñoz Game of probabilities reveals a phantasmagorical unreality, in an unpredictable mosaic, that invites personal continuation.

DOUBLE BIND: THE OTHER SIDE OF THE GAZE

The self-knowledge issue is a fundamental one for Humanism, both during the Renaissance and for the contemporary artists gathered by the Sorigué Foundation in its Lleida museum and in the different sites of the Balaguer production plant. The most spectacular, currently (waiting for others already scheduled) is the above-mentioned Double Bind, a work by Juan Muñoz. The term that defines the installation comes from the psychology field and refers to the lack of coordination that occurs in some individuals, in those situations in which verbal communication is accompanied by attitudes or non-verbal manifestations that seem to contradict what is expressed.

Double Bind shows its best virtues in the current location, also working as representative of the values and the faith in art -as a means for educating- of the Sorigué Foundation. In that industrial enclave we find an apparently empty silo, divided into two levels. After descending a slightly sloping ramp, stairs invite to walk upstairs and contemplate the work. But there’s nothing there, except for a series of scattered skylights. The overtures are of square shape, they seem traversed by light, even if some are intuited false. This trompe l’oeil effect is complemented by the incessant rattle of an elevator that communicates both areas. When we walk back, and we descend to the hardly illuminated ground floor -a cavernous sub-world-we discover the truth of an unthinkable connection.

The classical and anti-academic figures of Juan Muñoz inhabit a bordering space. Their grimaces inquire answers and trigger uncertainty. What these human beings do -so similar and different from us- and why they are there is something that we do not reach to know.

A mere return to ascetic Platonism is not proposed by installation -contrasting the falsity of appearance with the essential immutability of forms pure that shine in the light of intelligence- nor an inverted Platonism -as a recreation in the a confused vision- but rather a kind of invitation to run through unexpected paths, through gaps in chiaroscuro inhabited by new and strange beings, without certainty of what will happen next despite expectations (or because of expectations, that are confirmed wrong). The classical and anti-academic figures of Juan Muñoz inhabit a bordering space, showing grimaces or attitudes that demand answers and trigger uncertainty. What these human beings do -so similar and different from us- and why they are there, specifically, and not in another place, it is something that we do not reach to know. It is something that arouses admiration and restlessness, because it challenges, arouses questions without a simple answer.

SYNERGIES OF CONTEMPORARY ART

All this happens within the framework of a factory, a markedly industrial site that, as they explain, is orchestrated according to parameters of energy efficiency and use of the earth’s resources (from the raw material itself for construction, to the fruit of the surrounding olive trees, being even the bones of the fruit reused). One of the challenges of the 21st century, perhaps the most pressing and complex, is precisely that which concerns the management of natural resources, intimately connected with the production and sustainable use of energy.

“PLANTA articulates our way of understanding the return through art, in its confluence with architecture, landscape, science, knowledge and business”, the Sorigué Foundation explains.

The industrial landscape, which more than a century ago made possible a change in living conditions, it is still in the process of transformation, not only in the context of cities, where -as we know- factories have become public spaces. We can cite such well-known cases as the Tate Modern, the old Bankside power plant in London or -even more familiar, for many- the Caixaforum space, in the modernist Casaramona Factory. Also in Barcelona, it is pertinent to mention the space of the Fabra i Coats, turned into a centre for contemporary creation. Without a doubt it is a happy coincidence, that the efficient production places are transformed into showcases for the exhibition of the leading creativity, an idea that emphasizes the Foundation with its flagship project: “PLANT articulates our way of understanding the return through art, in its confluence with architecture, landscape, science, knowledge and the company”.

The new millennium demands a new twist to enhance the change of paradigm, more aware of the need to take care of the planet. And the Sorigué group has not only received different awards that demonstrate the efficiency of its model, but also commits itself to carrying out tasks, by means of its Foundation, that deal with awareness of sustainability, improving the conditions of life of some of the less favoured sectors of the population, and the possibility of educating through art -specifically, contemporary art- contributing thus to the promotion of a valuable intangible: the configuration of a conscious and critical gaze.