[dropcap letter=”A”]

ppeared coincidentally the same year as Planet of the Apes, that pioneering work suggests some of the consequences of the hypertrophy of technology, regarding both the most evolved human beings, practically apathetic scientists, and the super-intelligent on-board computer, HAL, which ends up developing pathological feelings. In addition to the thriller plot, Kubrick‘s film illustrates hallucinatory evolutionary leaps, induced by the presence of that “thing” essentially inapprehensible, insinuating a new understanding of space-time through images of unusual pregnancy, that music (from a Strauss waltz de Ligeti’s Atmosphères, including, also, the famous symphonic version of the Nietzschean Zarathustra) anchors in the memory of the spectator, and that we have recently rediscovered in Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival.

Fantastic cinema includes horror films and science fiction, categories that are not isolated, because in the representation of the impossible -what is feared or desired- the dark face of progress is often revealed

The topical contrast between an extreme rationality and the dictatorship of the irrational is as fantastical and old as romantic fictions, on which many of the early science and horror films are based, such as J. Searle Dawley’s Frankenstein (1910) or Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde that starred in 1920 John Barrymore. Since, fantastic cinema, far from being a minor genre, is the fundamental genre -practically foundational- of cinematography. Georges Méliès had already shown it years before with his Journey to the Moon of 1902. Being an illusionist and a theatre man, what could be more fascinating than the possibility of realizing fantasy, of really showing what is considered impossible or unreal? That is why many of his films show appearances and disappearances, as well as several metamorphoses, very successful at the time. From year 1908 is the series of transformations entitled Fantasmagorie by Emil Cohl, which anticipates the genre of animation through drawing. Following this laborious path in 1914, the first Jurassic creature (the adorable Gertie the Dinosaur) is “resurrected”, while in 1918 The Ghost of Slumber Mountain -more known as The Lost World– manages to reproduce, thanks to mechanical monsters, the fearsome possibility of an encounter with extinct species.

The topical contrast between an extreme rationality and the dictatorship of the irrational is as fantastical and old as romantic fictions, on which many of the early science and horror films are based, such as J. Searle Dawley’s Frankenstein (1910) or Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde that starred in 1920 John Barrymore. Since, fantastic cinema, far from being a minor genre, is the fundamental genre -practically foundational- of cinematography. Georges Méliès had already shown it years before with his Journey to the Moon of 1902. Being an illusionist and a theatre man, what could be more fascinating than the possibility of realizing fantasy, of really showing what is considered impossible or unreal? That is why many of his films show appearances and disappearances, as well as several metamorphoses, very successful at the time. From year 1908 is the series of transformations entitled Fantasmagorie by Emil Cohl, which anticipates the genre of animation through drawing. Following this laborious path in 1914, the first Jurassic creature (the adorable Gertie the Dinosaur) is “resurrected”, while in 1918 The Ghost of Slumber Mountain -more known as The Lost World– manages to reproduce, thanks to mechanical monsters, the fearsome possibility of an encounter with extinct species.

Fantastic cinema in fact includes horror films and science fiction films, categories that are not isolated, because in the representation of the impossible -what is feared or longed for- the dark side of progress is often revealed, which makes it possible that strange reality, in fact, through dystopian visions. A well-known example is Metropolis by Fritz Lang (1927), in which the marvels of scientific advances, in the form of an automated life, become possible thanks to the work of a few, under the surface of the city. This system will be terribly disrupted because of the first artificial creature, replicant of the adorable and peaceful Maria; the robot that, with its very appearance, will bring death and destruction. Hence, futuristic design coexists with gothic scenarios, and ultra-efficient means of transport with images and medieval themes -like the Dies irae, a song that announces the end of time- in paradoxical feedback.

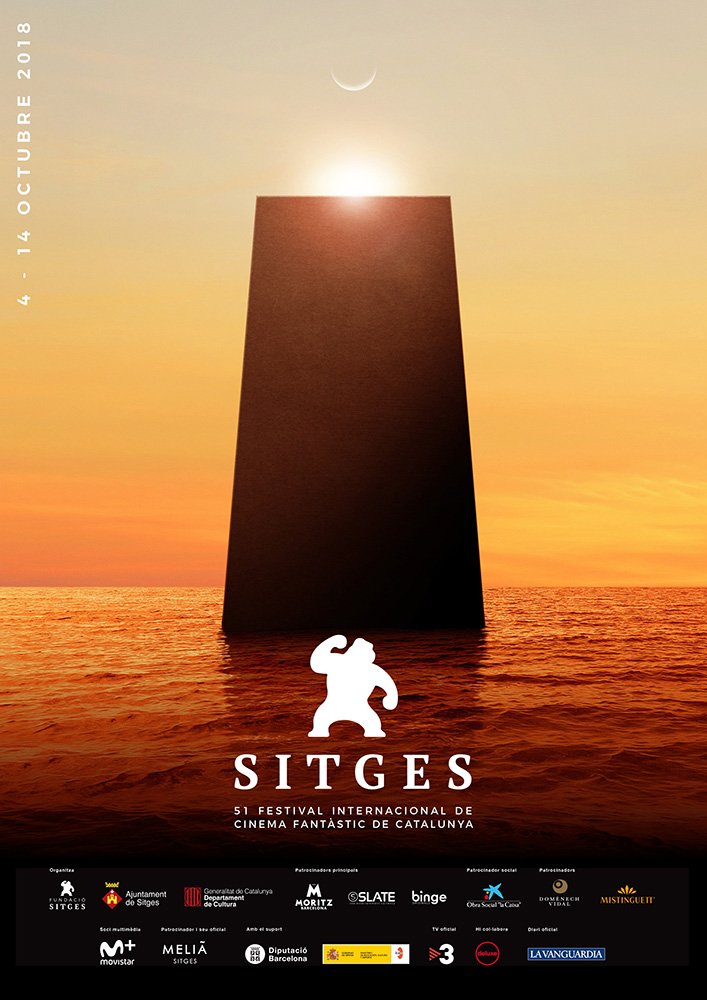

The current edition of the Sitges Festival is not only devoted to one of the most obsessively perfectionists filmmakers, in the recreation of possible worlds that enables film fiction -Stanley Kubrick- but also awards prizes to outstanding artisans of that hybrid and total genre. The great honorific prize will be granted to the director Peter Weir, author of films of varied style, among which the Baroque The Truman Show is remembered. A character close to Calderon de la Barca’s Segismundo (here, Jim Carrey) is tragicomically trapped -without knowing it, a priori- in a world that is nothing more than a huge set. His adventures and misadventures are a reality for the viewers, fascinated by the unconsciousness and authenticity of the actor (who does not know that he is). The identification of the viewer of the film with those TV spectators is inevitable, as well as -eventually- with the life, restricted in liberties, of the protagonist. The condition of being misunderstood as the protagonist alternates with that of being part of the chorus that sings, celebrates or cries the fate of the hero, from a highly empathic distance. In this way the essence of cinematographic fantasy is reproduced, the vision that unfolds and is realized from a position only apparently passive, as taught by Hitchcock in Rear Window.

The representation of fantasy provokes an excess of reality or surrealism that coexists perfectly with everyday reality, no matter how sensitive the viewer may be.

Another winner of an honorary prize, in the actor category, is Ed Harris, who characterized precisely the director in Weir’s fiction. Lovers of the series will recognize him after his role as a timeless outlaw, trapped -in this case voluntarily- in the recreation of Westworld. This successful HBO series stages a theme park without law, populated by automata of human appearance, that are left to endure every kind of experience from visitants with little awareness of their artificial condition, which points to powerful links with an essential title for science fiction, such as Blade Runner. Most interesting fact of the series, in this same sense, lies in the exploitation of the ambiguous line that separates and brings together human and artificial beings: the first ones showing manifestly irrational behaviors (violence / desire), the others increasingly being aware of themselves, with a memory that develops through feelings associated with their past life, and even his feared ending, in the line of that final monologue (“like tears in rain…”) solemnly declaimed by the replicant Ridley Scott’s film. This occurs in front of an astonished Harrison Ford, that has he been just saved by the murderer only to hear his story -to be a spectator- and safeguard his testimony beyond time, an activity that was considered to be exclusively “human”.

Together with Ed Harris, Nicolas Cage is the other actor who will receive that award, starring in films like Wild at Heart, Leaving Las Vegas or -since we are in the mood for referring mysterious (and joyous) “splittings”- of the essential Adaptation by Spike Jonze. In this bizarre sequel to Being John Malkovich, lavish in metafiction effects, Cage represents both Charlie Kaufmann -screenwriter of that film- and his twin brother, Donald (aspiring screenwriter in fiction, but completely non-existent in real life… despite being nominated for the Oscars, Golden Globe and British Academy Awards, having appeared in the credits with Charlie, as responsible for the screenplay!). The representation of fantasy provokes that excess of reality or surrealism that coexists perfectly with everyday reality, no matter how sensitive the viewer may be to his day-to-day life.

There are many films that can be seen in the Official Section of the contest, and that abound in the existence of possible worlds, similar or related to the allegedly real. In addition to the great names -Lars von Trier, with the premiere of his The House that Jack Built, for example – attention is paid to North American alternative production and the creators of our closest context, summing up altogether a highly attractive program. We cannot conclude without remembering one of the most wanted presences: the performance of John Carpenter, author of memorable horror films, as well as soundtracks composer.