There are things that only happen once in a lifetime....

There are many Inuit legends about the northern lights. Westerners,...

The audiovisual sector has a motto that will always prevail:...

Everything seems to indicate that agriculture and cattle-raising stand on...

The two artists embrace each other in a joint exhibition...

Since the Walkman we have walked from one place to...

In a few years on the market, Tesla has established...

Would you like to walk around with the Giocconda under...

The Museu Marítim will host on October 28 the great...

The importance of the logistics and transport industry is unquestionable....

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”A”]

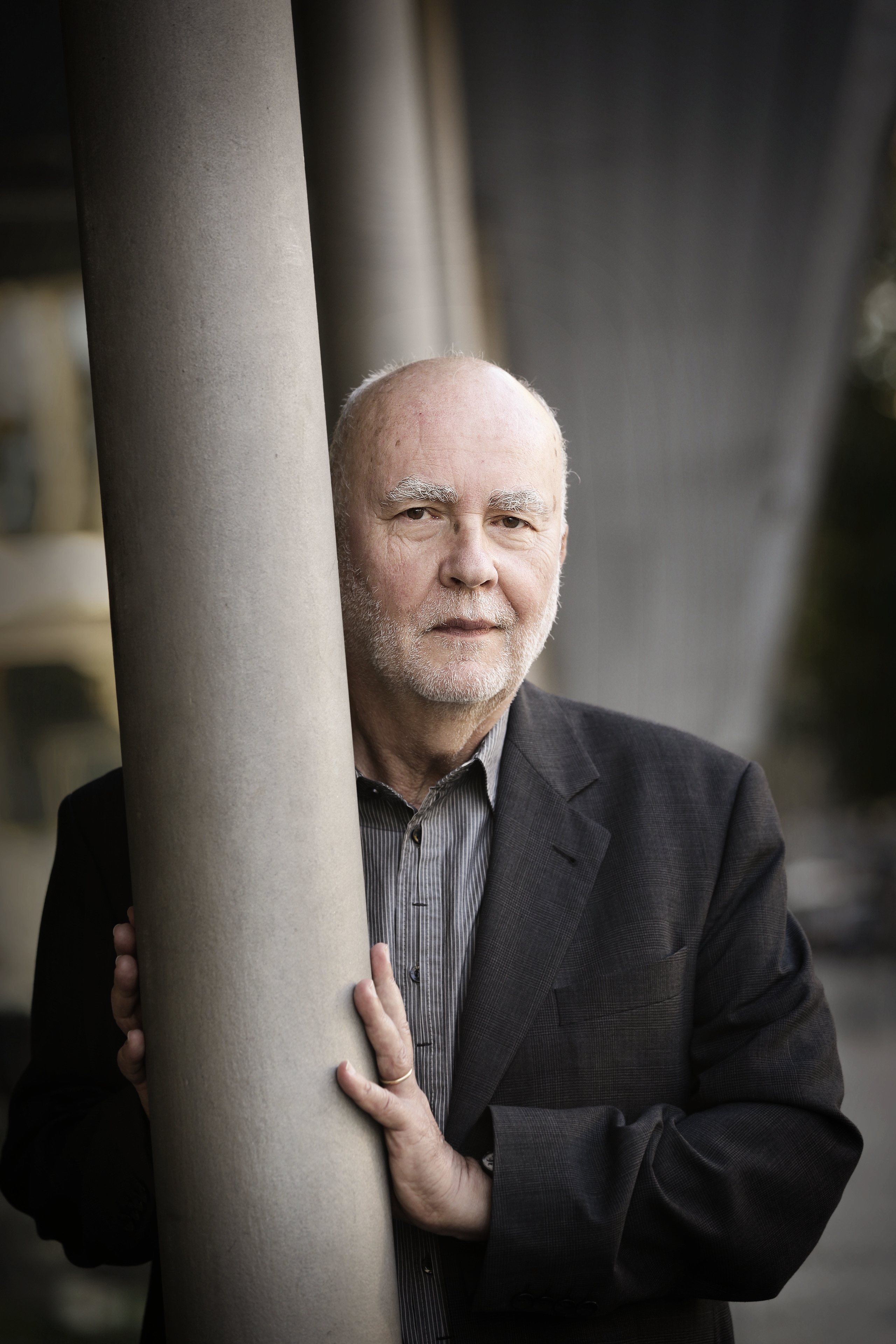

dam Zagajewski walks into the Rambla from Centre d’Art Santa Mònica. The yellow leaves of the tree tops converge into the silhouette of Columbus’ statue, with its bronze finger pointing to the sea. The Polish poet has always lived on quicksand. Born sixty-nine years ago in Lviv, the Yalta Conference that gave half of Europe to the Russians, forced his family to move to Gliwice. In 1945, his cousins, grandmothers, uncles and neighbours met again in that city, which had just become Prussian: “At school I used to study Russian and Latin; I also took private tuition of English and German. The fact that my family had moved —they were forced to— from Lviv to Gliwice illustrates the great transformations that were taking place. My elders lost their memories, saddened in that ugly city that would see them die…”

After Gliwice came Krakow: young Zagajewski studied Philosophy. In the seventies, he joined a movement opposed to the Communist régime: “I felt good as a person, but did not feel quite as a writer. I was finding it difficult to reconcile politics and literature…”. Together with Julian Kornhauser, he co-authored the stunning manifesto The non-represented world. In Poland he is identified with the 68 Generation, but his rebellious character owes little to the Sorbonne. In the countries of the Warsaw Pact, he points out, we “protested because tradition had been betrayed, not in the sense of museums or bourgeois customs, but as regards decency of human beings. On the other hand, Paris’ students only fought against tradition”.

On undersigning in 1975 the Letter of the 59 drove him to exile in Paris. The look of the poet focuses on more cities now: Berlin, Houston and Chicago, in whose university he is now teaching literature. He remembers Western Berlin in the early 1980s as “the weirdest synthesis of the former Prussian capital city with a shallow city, fascinated by Manhattan and the avant-gardes: sometimes I had the feeling that local intellectuals and artists saw the Wall as yet another wisecrack by Marcel Duchamp”.

In Paris —his current place of residence—, Zagajewski is experiencing the secret of eternal youth. In Houston and Chicago, the American passion of his juvenile reading. After the 11-S terrorist attacks, the poet paid tribute to the victims. The New Yorker page, which normally showed cartoons, the 69-year-old writer and professor recalls the verses of a childhood also marred by destruction. Those ashy days inspired an unheard of epic of compassion: “Try to praise the mutilated world / Remember June’s long days / and wild strawberries, drops of rosé wine / The nettles that methodically overgrow / the abandoned homesteads of exiles”.

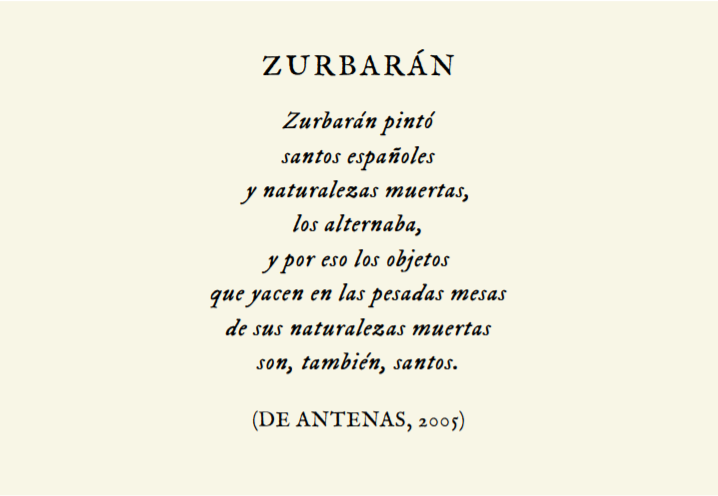

Although his works are in English, Zagajewski was not yet a popular poet. When editor Jaume Vallcorba included his name in the catalogue Acantilado, his collection of poems Desire became a bestseller. His collections of poems Going to Lviv, Canvas, Land of Fire, Desire, Antennas and Unseen Hand alternate with essays —literary or memoirs— Solidarity, Solitude, A defense of ardor and Two Cities. On the face of the “save yourself” principle, the author vindicates a solitary heroism of sorts; a lyric tinged by memories: he composes poems with the entries of an encyclopaedia of tragic European paradoxes. Having lived in a Poland broken up by totalitarisms hardened his character. Once again, mutilation… “You gathered acorns in the park in autumn and leaves / eddied over the earth’s scars / Praise the mutilated world and the gray feather a thrush lost, / and the gentle light that strays and vanishes / and returns”.

When his editor, the dearly missed Vallcorba, confronted his last summer, Zagajewski dedicated “Chacona”, a poem included in his latest book Asymmetry, published a few months later. The poet imagines Bach “in the rancid air of a dark church/ solitary like the pilot of a mail plane” playing the keyboard of the organ. Solitary and solidarious, this poem narrates losses, just like in his previous work, Invisible Hand. Toponymies in Polish, French, English, German… The four cities of a life, four kaleidoscopes to view the world: “First, Poland, teaches me my family tradition. Then Berlin shows me German literature, and its poetry and its –now forgotten- infinite zest. Thirdly, Paris, the landscape of French culture, with its shrewd intelligence and Jansenist morality. The fourth, Houston and Chicago is Shakespeare, Keats and Robert Lowell, the literature of the concrete, passion and conversation…”

A Marx who inspired brutality with a human face appears in his work in his last winter in cold and wet London: “I suspected having proposed the world / only one new form of hopelessness”, writes Zagajewski. On the face of left-wing populism that keeps alive the author of “The Capital”, he responds with an authority of someone who suffered in his flesh the “real socialism”. Revisiting Marx is regarded as “a conservative idea because it does but resuscitating old utopias, a mechanical repetition of failed systems”. The Europe that hesitates with Putin, his hands on Ukraine and the gas tap have not made it lose hope. His poem “Europe is already sleeping” is an antidote against banner anti-Americanism: “When Europe finally sleeps tight, / America will watch / over the poor and quiet world, / with suspicion, like a younger sister”. Grown from the ashes of the Holocaust, Zagajewski refused to believe that, after this, writing poetry was no longer possible: “Poland became a huge Jewish cemetery, the Shoah country. After the ghetto surrendered, the remaining population made for death camps and the Wehrmacht turned Warsaw into rubble. Nature reconquered this city: from the ashes of the buildings the birds made their nests and the flowers bloomed: ¡A true paradise for ecologists!” To decorative poets, he opposes the transparency of his admired Herbert and Milosz: “We don’t live for poetry, but because it makes us listen to another human being. It is a vehicle that cannot be worshipped, and least of all, Heaven forbid, worshipped…” Poetry as survival: “Instead of marble, we have metaphors and similes. Rubble often allows us to build a new city. Language, like the sun, can comfort human beings. Enchanting the world should be the poet’s duty. When we stop naming the world, it disinherits us and the only thing left is an empty rhetoric, a hollow sound…”

Zagajewski rests his glance on La Rambla. We tell him that, right in front, behind the trees, stands the hotel Cuatro Naciones: it is there that Chopin stayed with George Sand on his Barcelona stopover, on the way to Mallorca. We talk about Spain. His poem “Flags” describes “wrinkled sheets of heroes” that cover our eyes … To this errand poet, the boat people is the only nation without nationalism: “I find it difficult to analyze the degrees of patriotism. I cannot either condemn the good-willed patriots, although there is a thin red line between well-intentioned patriotism and the madness of nationalism that claims that we are the best…”

He received in 2010 the Europa Award of poetry, and is a frequent candidate to the Nobel Prize. Zagajewski enters the room that is waiting for his poems to be recited. Slight throat clearing. The poet is eight years old again… “I had no talent for music. / I’d better study languages…” After that unsatisfactory class, the boy-passerby from the city of Gliwice comes back home crestfallen: “And thought bitterly, with satisfaction, / that I had only my tongue left, only the words, images / only the world…” No less than the world.

[dropcap letter=”A”]

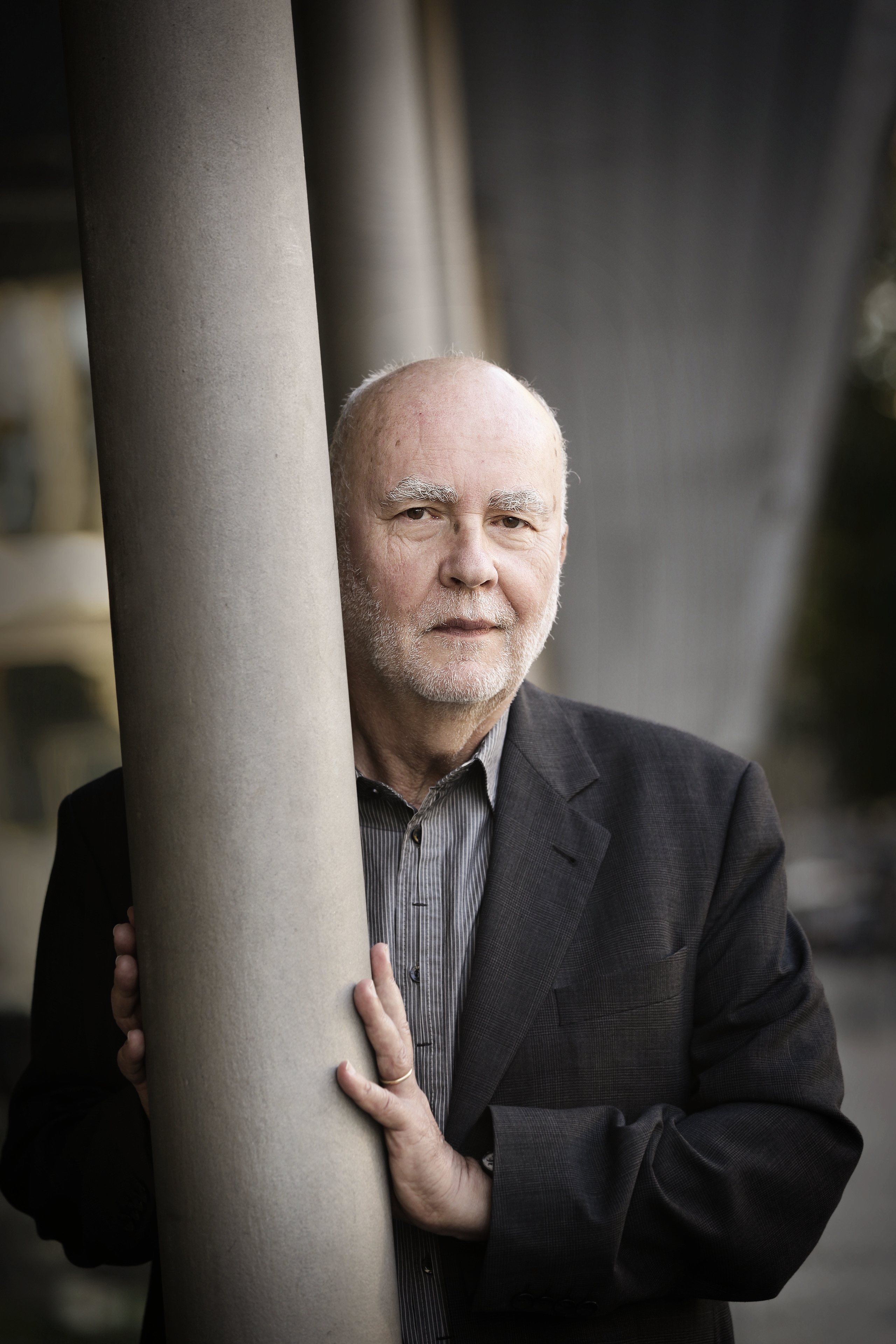

dam Zagajewski walks into the Rambla from Centre d’Art Santa Mònica. The yellow leaves of the tree tops converge into the silhouette of Columbus’ statue, with its bronze finger pointing to the sea. The Polish poet has always lived on quicksand. Born sixty-nine years ago in Lviv, the Yalta Conference that gave half of Europe to the Russians, forced his family to move to Gliwice. In 1945, his cousins, grandmothers, uncles and neighbours met again in that city, which had just become Prussian: “At school I used to study Russian and Latin; I also took private tuition of English and German. The fact that my family had moved —they were forced to— from Lviv to Gliwice illustrates the great transformations that were taking place. My elders lost their memories, saddened in that ugly city that would see them die…”

After Gliwice came Krakow: young Zagajewski studied Philosophy. In the seventies, he joined a movement opposed to the Communist régime: “I felt good as a person, but did not feel quite as a writer. I was finding it difficult to reconcile politics and literature…”. Together with Julian Kornhauser, he co-authored the stunning manifesto The non-represented world. In Poland he is identified with the 68 Generation, but his rebellious character owes little to the Sorbonne. In the countries of the Warsaw Pact, he points out, we “protested because tradition had been betrayed, not in the sense of museums or bourgeois customs, but as regards decency of human beings. On the other hand, Paris’ students only fought against tradition”.

On undersigning in 1975 the Letter of the 59 drove him to exile in Paris. The look of the poet focuses on more cities now: Berlin, Houston and Chicago, in whose university he is now teaching literature. He remembers Western Berlin in the early 1980s as “the weirdest synthesis of the former Prussian capital city with a shallow city, fascinated by Manhattan and the avant-gardes: sometimes I had the feeling that local intellectuals and artists saw the Wall as yet another wisecrack by Marcel Duchamp”.

In Paris —his current place of residence—, Zagajewski is experiencing the secret of eternal youth. In Houston and Chicago, the American passion of his juvenile reading. After the 11-S terrorist attacks, the poet paid tribute to the victims. The New Yorker page, which normally showed cartoons, the 69-year-old writer and professor recalls the verses of a childhood also marred by destruction. Those ashy days inspired an unheard of epic of compassion: “Try to praise the mutilated world / Remember June’s long days / and wild strawberries, drops of rosé wine / The nettles that methodically overgrow / the abandoned homesteads of exiles”.

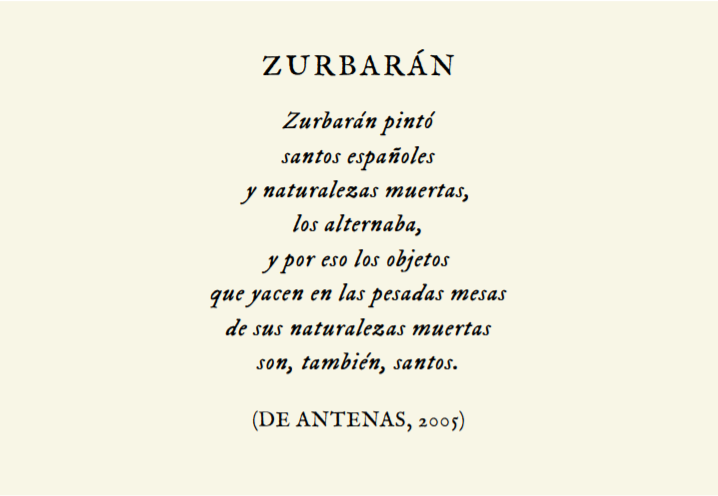

Although his works are in English, Zagajewski was not yet a popular poet. When editor Jaume Vallcorba included his name in the catalogue Acantilado, his collection of poems Desire became a bestseller. His collections of poems Going to Lviv, Canvas, Land of Fire, Desire, Antennas and Unseen Hand alternate with essays —literary or memoirs— Solidarity, Solitude, A defense of ardor and Two Cities. On the face of the “save yourself” principle, the author vindicates a solitary heroism of sorts; a lyric tinged by memories: he composes poems with the entries of an encyclopaedia of tragic European paradoxes. Having lived in a Poland broken up by totalitarisms hardened his character. Once again, mutilation… “You gathered acorns in the park in autumn and leaves / eddied over the earth’s scars / Praise the mutilated world and the gray feather a thrush lost, / and the gentle light that strays and vanishes / and returns”.

When his editor, the dearly missed Vallcorba, confronted his last summer, Zagajewski dedicated “Chacona”, a poem included in his latest book Asymmetry, published a few months later. The poet imagines Bach “in the rancid air of a dark church/ solitary like the pilot of a mail plane” playing the keyboard of the organ. Solitary and solidarious, this poem narrates losses, just like in his previous work, Invisible Hand. Toponymies in Polish, French, English, German… The four cities of a life, four kaleidoscopes to view the world: “First, Poland, teaches me my family tradition. Then Berlin shows me German literature, and its poetry and its –now forgotten- infinite zest. Thirdly, Paris, the landscape of French culture, with its shrewd intelligence and Jansenist morality. The fourth, Houston and Chicago is Shakespeare, Keats and Robert Lowell, the literature of the concrete, passion and conversation…”

A Marx who inspired brutality with a human face appears in his work in his last winter in cold and wet London: “I suspected having proposed the world / only one new form of hopelessness”, writes Zagajewski. On the face of left-wing populism that keeps alive the author of “The Capital”, he responds with an authority of someone who suffered in his flesh the “real socialism”. Revisiting Marx is regarded as “a conservative idea because it does but resuscitating old utopias, a mechanical repetition of failed systems”. The Europe that hesitates with Putin, his hands on Ukraine and the gas tap have not made it lose hope. His poem “Europe is already sleeping” is an antidote against banner anti-Americanism: “When Europe finally sleeps tight, / America will watch / over the poor and quiet world, / with suspicion, like a younger sister”. Grown from the ashes of the Holocaust, Zagajewski refused to believe that, after this, writing poetry was no longer possible: “Poland became a huge Jewish cemetery, the Shoah country. After the ghetto surrendered, the remaining population made for death camps and the Wehrmacht turned Warsaw into rubble. Nature reconquered this city: from the ashes of the buildings the birds made their nests and the flowers bloomed: ¡A true paradise for ecologists!” To decorative poets, he opposes the transparency of his admired Herbert and Milosz: “We don’t live for poetry, but because it makes us listen to another human being. It is a vehicle that cannot be worshipped, and least of all, Heaven forbid, worshipped…” Poetry as survival: “Instead of marble, we have metaphors and similes. Rubble often allows us to build a new city. Language, like the sun, can comfort human beings. Enchanting the world should be the poet’s duty. When we stop naming the world, it disinherits us and the only thing left is an empty rhetoric, a hollow sound…”

Zagajewski rests his glance on La Rambla. We tell him that, right in front, behind the trees, stands the hotel Cuatro Naciones: it is there that Chopin stayed with George Sand on his Barcelona stopover, on the way to Mallorca. We talk about Spain. His poem “Flags” describes “wrinkled sheets of heroes” that cover our eyes … To this errand poet, the boat people is the only nation without nationalism: “I find it difficult to analyze the degrees of patriotism. I cannot either condemn the good-willed patriots, although there is a thin red line between well-intentioned patriotism and the madness of nationalism that claims that we are the best…”

He received in 2010 the Europa Award of poetry, and is a frequent candidate to the Nobel Prize. Zagajewski enters the room that is waiting for his poems to be recited. Slight throat clearing. The poet is eight years old again… “I had no talent for music. / I’d better study languages…” After that unsatisfactory class, the boy-passerby from the city of Gliwice comes back home crestfallen: “And thought bitterly, with satisfaction, / that I had only my tongue left, only the words, images / only the world…” No less than the world.