[dropcap letter=”I”]

n the past, the future was an unfathomable location. The journey to the moon was done through literature and observing the sky, as it was not intended as an exercise for learning about the movement of heavenly bodies but as a way of predicting our fate. Nevertheless, in the 21st century, the future has crossed the gateway to the present. Technological dreams are now experienced to the full. Victor Hugo said in his wonderful essay The Promontory of Sleep “when a man does not have a dream, he searches for it. Tea, coffee, a cigar, a pipe, hookah, cauldron, incense: all these are procedures towards dreaming”. Dreams that our time has failed to give us do not contain pleasurable sensuousness but the fast pace of excitement. We want to embrace novelty, we want to fill the gap of doubt, we strive to clarify and authenticate our world with data, algorithms and virtual reality. We can state that the future governs our lives while the past only weakens our assertiveness of past successful times. Ours is a time where reality, either virtual or of any other type, prevails, and the overriding terms are immersion, experiences and interaction, while in the past, the prevailing words were dream, enchantment and charm.

Paradoxically, our future is not only changing what and how we live, but also who we are, in other words, our human condition. These are times in which we celebrate technological and scientific changes as a victory of our intelligence, but what is really changing is our way of existing in the world. Since men are not essential for women to be able to procreate, since our efforts towards productivity are substituted by robotics and better life expectancy, and we can be like Methuselah, who lived to 969 years of age, so the Bible says, we should begin wondering about the present of the human species and its position in the future world. This future will one day irrupt with all its transforming might of reality.

The challenges of robotics, its advances and capacity to define the present, show that our present time needs to open up discussions and develop critical thinking in order to be able to pose the right questions that will neatly reveal in what ways an all-encompassing robotic future can affect humans

The present of our species is already tightly linked to robotics. A few weeks ago, chronicler and writer Arturo San Agustín published his latest book suggestively entitled El robot que cree en Dios [The Robot that believes in God]. In the novel, San Agustín delves into the power of robotics to question faith, everything we believe in, and transhumanism as a step ahead from humanism. The book begins with the discovery of a robot caught in the act of crossing himself. We had always imagined robots as potential warriors of future armies, doing tasks that humans do not want to do anymore, taking care of or playing with our children, or even being our pets, but we had never imagined them with a degree of intelligence and precision sophisticated enough that would enable to have faith in something that transcends them; becoming humanized.

Before then, in Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? we had been warned about how robots tried to avoid planned obsolescence, avoid their own death and achieving the free will that humans disputed. Also in Isaac Asimov’s I robot, robots rebel against humans. But Arturo San Agustín’s novel takes a leap forward by asking himself what is the future of a human kind wavering between syncretism and robotics while traditional values and beliefs are undermined.

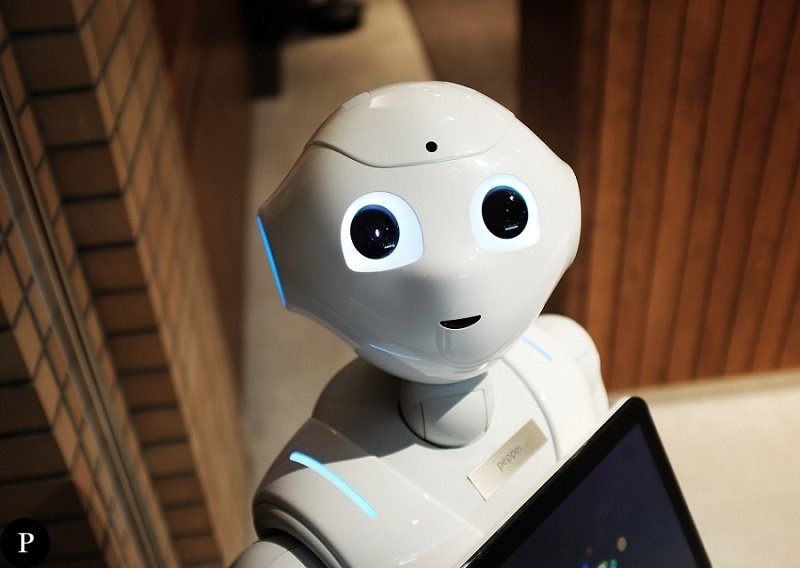

Delving into robotics, we can find robots doing tasks in hospitals, taking part in management boards of large corporations or welcoming guests in hotels or restaurants. This is the case of a hotel in the Canary Islands, which has contracted the services of a robot called Pepper to welcome their clients. In the essay La imparable marcha de los robots [The Unstoppable Advance of Robots], Andrés Ortega immerses us into their manifold utilities and warns us about the challenges we will be facing. On reading it, the author introduces us to the robot/baby seal cuddly, called Paro (in Spanish, Nuka), used to treat emotionally elderly people with Alzheimer syndrome; Hiroshi Ishiguro, Professor of Robotics at the University of Osaka, has built a robot, his alter ego, identical to himself, called Geminoid HI-1, as a robotics experience to work on the emotional side and making them more human. There is robotics in order to give mobility to people with physical disabilities, and allow them to give a rest to their arms, legs or other organs that have either deteriorated or organs whose abilities need to be pumped up. There is robotics applied to pleasure, as the old automatons in Federico Fellini’s Casanova, a film in which Giacomo Casanova makes love to a female automaton. There is robotics to correct malfunctions of an ageing society, like the Japanese society, whose population will, in the future, have 30% of people older than 65, in front of the current 23%. In this case, robotics will be an effective form to mitigate this problem.

But the key question that frightens many governments is the negative impact of robotics at the workplace. We have even tackled this problem in electoral programmes, as some French political parties have recently done. They propose that businesses contracting robots should pay taxes, as this would increase unemployment rates. The controversy between collaborating versus resisting the advance of robotics is revealed in data obtained by research on computerization at European workplaces. The study warns us that, in less than two decades, between 40% and 60% of the European workforce could be seriously affected. Andrés Ortega states that, in Spain, as much as 55.3% of jobs made by humans could be lost.

The challenges of robotics, its advances and capacity to define the present, show that our present time needs to open up discussions and develop critical thinking in order to be able to pose the right questions that will neatly reveal in what ways an all-encompassing robotic future can affect humans, from our everyday life to our ways of thinking. Perhaps the success of philosophical best-selling books in Europe stems from the compelling human need to try to understand, on reading, what is happening around us, and receiving answers about the present and the future of our species.