A tree in the city is much more than ornamentation...

Banco Sabadell, with the collaboration of the University of Barcelona,...

The printed book is a technological device dating back to...

Entrepreneurs' Organization promotes entrepreneurship in community and from a holistic...

“Science is alive and it’s part of culture. Science is...

The company settled in the Baix Empordà manufactures up to...

There is no need, anymore, to go to Silicon Valley...

Graduated in Biological Sciences from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona...

Barcelona has been an outstanding entrepreneurial centre for the technology...

Fatigue, vomiting, hair loss... We have assumed that, to be...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”F”]

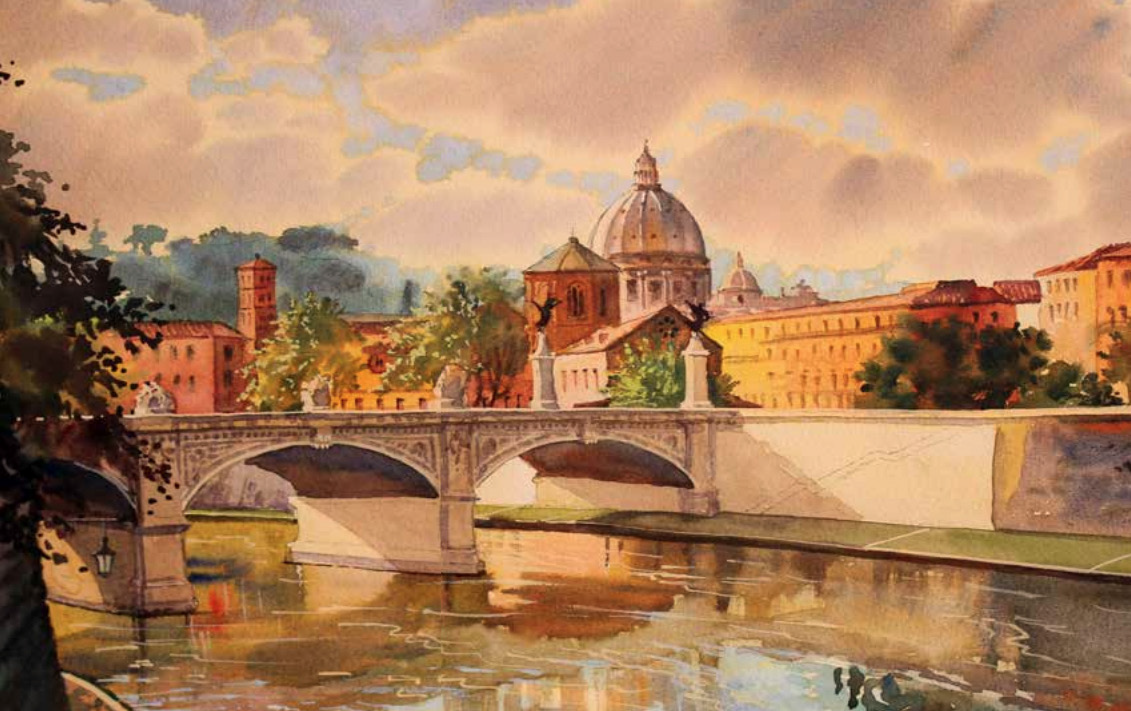

rom my flat on top of Mount Gianícolo —the eighth Roman hill, as it should be called, in all fairness— I see a unique view of the city: domes and steeples of magnificent churches, towers of sumptuous palaces, robust imperial walls and gardens with cypress trees jutting out. To my feet, the rooftops of the nearby district of Trastevere and, beyond, sketching out the background of this living Roman altar piece, the faraway curve of the mountain ranges descending from the north and forming, to the east, a jagged bluish line. I have the impression that the entire city of Rome is before me, although the Vatican’s view remains unseen, hidden between treetops to the west. Today is an autumn weekend, sunset closing in, and flocks of starlings, retiring to sleep inside the treetops by the river Tiber, gather and form thick mobile clouds, in a regular and frenzied dance whose rhythms are even unknown to themselves.

This is the best time to stroll down to the old city, or what remains of that imposing imperial capital city whose palaces were devastated by barbaric tribes and razed to the ground, removing old stones to build their mansions, the great Renaissance gentlemen. Silence prevails in the temples of gods and goddesses, and on the hills where the Roman emperors put up their homes: the Palatino, the Capitol. On nights of full moon, this silence is even more alive, as if the gods that yesterday’s gods whispered to us, “we are still here”. Ancient Rome murmurs at night inside the Imperial Forums, and tells us about its war and art wars in the Forums of Augustus and Trajan, in Constantine’s Arch and the columns of Antonina and Trajan. But the architectural king of this millennial imperial city is, without doubt, the Colosseum, a stadium built, not to worship gods, but to entertain the people. Time has left its trace —as well as the city’s invaders— and now resembles a jagged denture on its upper part. Nevertheless, despite the shattering, it is as impressive as the Acropolis of Athens.

The old circus, inaugurated by Emperor Titus in 80 AD, was intended as an entertainment for the people. A peculiar way of entertaining themselves, the Romans! The Colosseum was a theatre which, even, at times would change its sands into a swimming pool to stage sea battles. In fact, these battles were for real, and men would stab each other ferociously and they died by hundreds. Among these games were deadly combats between gladiators and fights against tigers, lions and bears. Likewise, as is well known, the sacrifice of the Christians, amidst the jaws of wild beasts: it is estimated that, in the years that these shows occurred, around seventy thousand Christian believers perished on the sands of the Colosseum. Hard to believe, in nights of full moon, this quiet and noble place, on the last esplanade of ancient forums, would witness such brutality. The farcical poet Gioachino Belli ironized about it in a sonnet: “In the past, such mourning, such destruction, and now such peace! Oh, human modes! What a funny old world!, how everything changes!”.

But old Rome limps if you do not enter Agrippa’s Pantheon, slightly separated from the forums, where I go through almost daily in my Roman strolls and which I always visit even if it is only for a few minutes. This is the best preserved temple of all Antiquity thanks to Byzantine Emperor, Flavio Focas. It was a present from Pope Boniface IV, who decided to maintain it as it was originally, only changing the altars of the statues of pagan gods by those of saints and virgins. Specially impressive is its dome, the biggest in the city until that of the Vatican was built. Experts say that, at its center, they dug the big hole that now stands in the middle, through which gods could communicate with men. But I have the opposite feeling: that I can escape through the hole and talk to gods about yesterday. Those deities were extremely sinful and were closer to men just because of this. Perhaps this was the reason why, through a simple hole, you could access their homes.

The Pantheon houses something else: a marble sarcophagus, Rafael’s tomb. And it is, not only because his remains are buried there, but also because of the beautiful carved epitaph in remembrance of the painter. I translate from Latin the stanzas, by poet-cardinal Pietro Bembo: “Here lies Rafael. When he was alive, Nature feared being defeated by him. When he died, Nature feared dying with him”. There may not be any other text in the world that honours an artist’s sepulchre, to such an extent. Rome is a strange city in his relation to art. This relationship is nowhere else to be seen. In Florence, New York, Paris or Madrid, in order to enjoy creative art, you must go to museums. Rome, instead, as Byron used to say, “is an open-air museum”. Here you can find a bicycle workshop inside the ruins of an ancient palace or a bank with a column of an imperial forum or a monolith of pharaonic Egypt in the middle of a square. And art, often, rises up to meet you unexpectedly, in the dark altar of a humble church that zealously guards the picture of a genius of painting and refuses to yield it to a museum.

Stendhal said in one of his books “what is really great should not bear any embellishment”. This is the key to understanding the relationship of Rome with art, as nothing is embellished, but natural. And this has been for centuries the task of Roman artists. This is why searching for them can become a difficult task. Curiously, the three great figures of Italian Renaissance are alluded to by their names, and we all know who they are: Leonardo —da Vinci—, Rafael —Sanzio— and Michelangelo —Buonarroti—. In other words: they are called as if they were family or friends. It is also noticeable that, except for Leonardo —there is hardly any of his works in Rome—, the other two can be found in numerous and different locations throughout Rome. To “see” Rafael and Michelangelo requires nearly one day for each of them, comfortable walking shoes for the unbearable cobbled Roman streets, the famous sanpietrini.

We track Rafael, prodigy spoilt child of the Renaissance, the genius born with the precocity of great artists. Leaving aside his works in other towns and cities in Italy and the world —like the magnificent Portrait of Cardinal of Museo del Prado in Madrid or the cartons of Royal Albert Hall in London—, there is a nearly secret route of Rafael in today’s Rome. Going down the Gianícolo to the city, I am faced with two choices: Via Garibaldi or the steep gardens that give onto Viale di Trastevere. I choose the former and, when I get to the foot of the hill, in a little square, turn to the left under an arch and give onto Villa Farnesina, former residence of a wealthy papal treasurer. The palace holds several frescos from the genius’ frescos and, above all, that of Galatea, directly from the painter’s palette. In another room, a rooftop beautifully decorated with mythological motives made mostly by the genius himself. The nudes abound in these works: the Renaissance artists never flinched at painting male sex or female breasts. However, pudically, female sex was always hidden.

Going up from the river, from treetops of banana trees and chestnut trees woven over the river Tiber, until I get to the Vatican. Once there, inside the big building, headquarters of the popes, I go through the rite of queueing up to visit the museums. It is worth doing because, after a long walk through galleries packed with extraordinary pictures and frescoes, we bump into the so-called Rafael’s stanze who, in tandem with his assistants, created one of the main masterpieces of Renaissance: the frescoes of four rooms, two of which were authored by Rafael himself, while the other two were made under his supervision by his assistants and pupils. In Stanza di Eliodoro, undoubtedly imposing is the fresco The liberation of Saint Peter. But it is Stanza della Segnatura that holds, in my opinion, the supreme work of this artist: The School of Athens. How to explain the grandeur of this painting? I can only think of an answer every time I see it: naturalness. Rafael creates this fresco in an imaginary space in time to highlight human wisdom, represented by Ancient Greece and recovered by Renaissance Rome. Plato and Aristotle are the main figures on it, on the way to the great arch, calm, solemn, before the gaze of Socrates. From all over, wise men: Euclides, Homer, Zoroastre. Funnily enough, as if in a joke, it is Rafael paints some of the faces of his contemporaries on relevant figures from the past. Plato’s face was that of Leonardo; Euclides’ face was Bramantes’s, Heraclitus’ face was Michelangelo, his rival! Rafael was a generous artist who recognized the talent of his adversaries. And The School of Athens reflects the faith of a good man in the hope that, while other contemporaries represented despair, e.g. Caravaggio, and often Michelangelo himself, the volcanic artist par excellence in the history of mankind, besides being a splendid painter, a sublime architect —Rafael also designed buildings— and a magnificent sculptor. His grandeur can, maybe, only be equalled by Leonardo. In Rome, one can track down his best works. The first of them all, of course, the sublime Vatican dome, classical lines, influenced by the Pantheon, and that this is the greatest in Christendom. If the power of popes —formerly political, now spiritual— has been one of the most sumptuous of the history of mankind, its best representation is the Basilica of Saint Peter, because of its esplanade, the imposing façade of its temple and the massive dome. And Michelangelo was one of its most renowned authors. Inside, there are two of the best examples of his flexibility: the Pietà, a marble sculpture representing the Virgin Mary crying over her dead son, a man too young to die; and the lavish Sistine Chapel, where one does not know whether it is God who takes the role of Manor it is Man who suddenly becomes God to deal the law of the Final Trial. We go up the staircase to San Pietro in Vincoli and admire the Moses that the artist carved on Julius II’s tomb. What energy from the guardian of the Tables of the Law! I see him, however, slightly scared about the burden of this responsibility. Michelangelo’s work does not stop there. There is the design of the beautiful Plazza del Campidoglio, with its solemn staircase and two beautiful buildings housing two museums of sculpture, one containing the beautiful equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, from classical Antiquity. There is also the façade to the harsh Palazzo Farnese, host to the Embassy of France. And the marbled Christ holding a cross before the major altar of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva.

Rome is much more than Michelangelo. Every day, I have to wander around this open-air museum to admire, for example, its Baroque legacy. Bleak Caravaggio is present in at least three Roman churches and museums of Villa Borghese and Palazzo Barberini. To admire the gifted sculptor and architect Bernini, you must go through many squares and other palaces and villas. As regards Spanish painter Velázquez, to witness some of his work means going to Gallery Doria Pamphili and shiver at the perverse look on pope Innocent X’s face. Nearly two days are needed to go through all the scenarios where the great Borromini designed the buildings, both religious and civil, or design his façades and interiors: the palaces de la Sapienza and Falconieri, the Oratorio dei Filippini, Santa Agnese di Agone, San Juan de Letrán and this precious jewel of the “perspective” of Palace Spada. This gallery flanked by columns with a small patio and a statue in the background, more than an architectural work, is the game of reason, a trickery of sizes, a view supposedly real of something that is unreal. Like art itself. From the top, in Gianícolo, I look down on Rome at dusk. There is so much to discover. Rome is eternal because it never ends.

[dropcap letter=”F”]

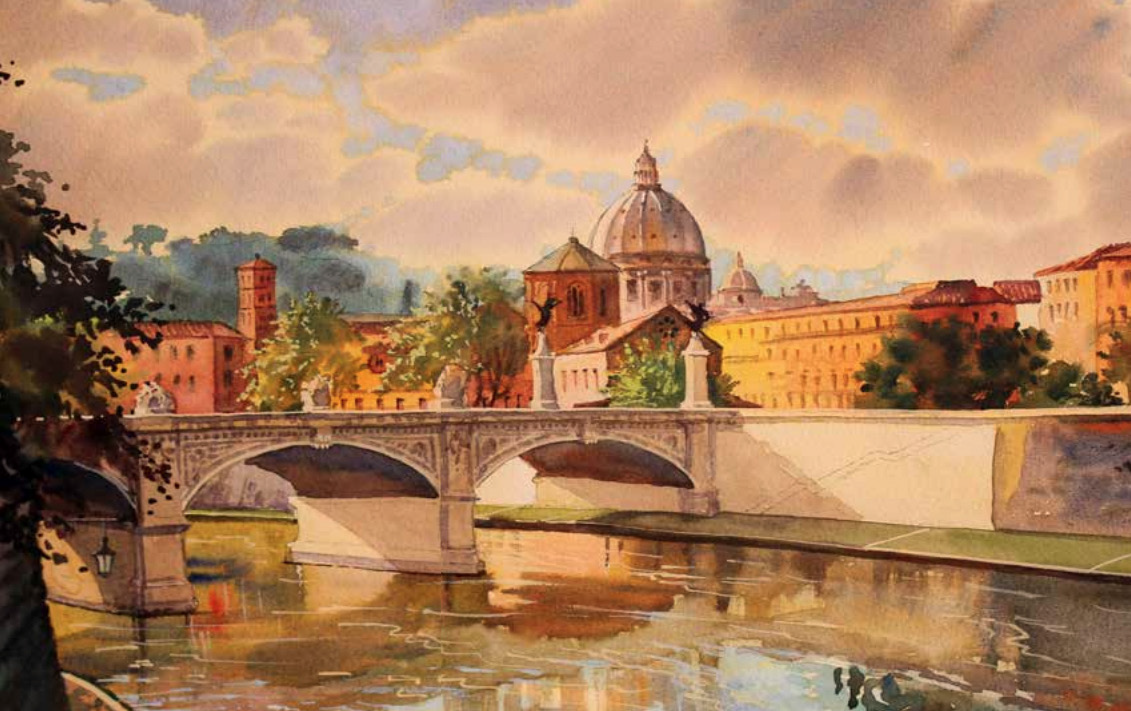

rom my flat on top of Mount Gianícolo —the eighth Roman hill, as it should be called, in all fairness— I see a unique view of the city: domes and steeples of magnificent churches, towers of sumptuous palaces, robust imperial walls and gardens with cypress trees jutting out. To my feet, the rooftops of the nearby district of Trastevere and, beyond, sketching out the background of this living Roman altar piece, the faraway curve of the mountain ranges descending from the north and forming, to the east, a jagged bluish line. I have the impression that the entire city of Rome is before me, although the Vatican’s view remains unseen, hidden between treetops to the west. Today is an autumn weekend, sunset closing in, and flocks of starlings, retiring to sleep inside the treetops by the river Tiber, gather and form thick mobile clouds, in a regular and frenzied dance whose rhythms are even unknown to themselves.

This is the best time to stroll down to the old city, or what remains of that imposing imperial capital city whose palaces were devastated by barbaric tribes and razed to the ground, removing old stones to build their mansions, the great Renaissance gentlemen. Silence prevails in the temples of gods and goddesses, and on the hills where the Roman emperors put up their homes: the Palatino, the Capitol. On nights of full moon, this silence is even more alive, as if the gods that yesterday’s gods whispered to us, “we are still here”. Ancient Rome murmurs at night inside the Imperial Forums, and tells us about its war and art wars in the Forums of Augustus and Trajan, in Constantine’s Arch and the columns of Antonina and Trajan. But the architectural king of this millennial imperial city is, without doubt, the Colosseum, a stadium built, not to worship gods, but to entertain the people. Time has left its trace —as well as the city’s invaders— and now resembles a jagged denture on its upper part. Nevertheless, despite the shattering, it is as impressive as the Acropolis of Athens.

The old circus, inaugurated by Emperor Titus in 80 AD, was intended as an entertainment for the people. A peculiar way of entertaining themselves, the Romans! The Colosseum was a theatre which, even, at times would change its sands into a swimming pool to stage sea battles. In fact, these battles were for real, and men would stab each other ferociously and they died by hundreds. Among these games were deadly combats between gladiators and fights against tigers, lions and bears. Likewise, as is well known, the sacrifice of the Christians, amidst the jaws of wild beasts: it is estimated that, in the years that these shows occurred, around seventy thousand Christian believers perished on the sands of the Colosseum. Hard to believe, in nights of full moon, this quiet and noble place, on the last esplanade of ancient forums, would witness such brutality. The farcical poet Gioachino Belli ironized about it in a sonnet: “In the past, such mourning, such destruction, and now such peace! Oh, human modes! What a funny old world!, how everything changes!”.

But old Rome limps if you do not enter Agrippa’s Pantheon, slightly separated from the forums, where I go through almost daily in my Roman strolls and which I always visit even if it is only for a few minutes. This is the best preserved temple of all Antiquity thanks to Byzantine Emperor, Flavio Focas. It was a present from Pope Boniface IV, who decided to maintain it as it was originally, only changing the altars of the statues of pagan gods by those of saints and virgins. Specially impressive is its dome, the biggest in the city until that of the Vatican was built. Experts say that, at its center, they dug the big hole that now stands in the middle, through which gods could communicate with men. But I have the opposite feeling: that I can escape through the hole and talk to gods about yesterday. Those deities were extremely sinful and were closer to men just because of this. Perhaps this was the reason why, through a simple hole, you could access their homes.

The Pantheon houses something else: a marble sarcophagus, Rafael’s tomb. And it is, not only because his remains are buried there, but also because of the beautiful carved epitaph in remembrance of the painter. I translate from Latin the stanzas, by poet-cardinal Pietro Bembo: “Here lies Rafael. When he was alive, Nature feared being defeated by him. When he died, Nature feared dying with him”. There may not be any other text in the world that honours an artist’s sepulchre, to such an extent. Rome is a strange city in his relation to art. This relationship is nowhere else to be seen. In Florence, New York, Paris or Madrid, in order to enjoy creative art, you must go to museums. Rome, instead, as Byron used to say, “is an open-air museum”. Here you can find a bicycle workshop inside the ruins of an ancient palace or a bank with a column of an imperial forum or a monolith of pharaonic Egypt in the middle of a square. And art, often, rises up to meet you unexpectedly, in the dark altar of a humble church that zealously guards the picture of a genius of painting and refuses to yield it to a museum.

Stendhal said in one of his books “what is really great should not bear any embellishment”. This is the key to understanding the relationship of Rome with art, as nothing is embellished, but natural. And this has been for centuries the task of Roman artists. This is why searching for them can become a difficult task. Curiously, the three great figures of Italian Renaissance are alluded to by their names, and we all know who they are: Leonardo —da Vinci—, Rafael —Sanzio— and Michelangelo —Buonarroti—. In other words: they are called as if they were family or friends. It is also noticeable that, except for Leonardo —there is hardly any of his works in Rome—, the other two can be found in numerous and different locations throughout Rome. To “see” Rafael and Michelangelo requires nearly one day for each of them, comfortable walking shoes for the unbearable cobbled Roman streets, the famous sanpietrini.

We track Rafael, prodigy spoilt child of the Renaissance, the genius born with the precocity of great artists. Leaving aside his works in other towns and cities in Italy and the world —like the magnificent Portrait of Cardinal of Museo del Prado in Madrid or the cartons of Royal Albert Hall in London—, there is a nearly secret route of Rafael in today’s Rome. Going down the Gianícolo to the city, I am faced with two choices: Via Garibaldi or the steep gardens that give onto Viale di Trastevere. I choose the former and, when I get to the foot of the hill, in a little square, turn to the left under an arch and give onto Villa Farnesina, former residence of a wealthy papal treasurer. The palace holds several frescos from the genius’ frescos and, above all, that of Galatea, directly from the painter’s palette. In another room, a rooftop beautifully decorated with mythological motives made mostly by the genius himself. The nudes abound in these works: the Renaissance artists never flinched at painting male sex or female breasts. However, pudically, female sex was always hidden.

Going up from the river, from treetops of banana trees and chestnut trees woven over the river Tiber, until I get to the Vatican. Once there, inside the big building, headquarters of the popes, I go through the rite of queueing up to visit the museums. It is worth doing because, after a long walk through galleries packed with extraordinary pictures and frescoes, we bump into the so-called Rafael’s stanze who, in tandem with his assistants, created one of the main masterpieces of Renaissance: the frescoes of four rooms, two of which were authored by Rafael himself, while the other two were made under his supervision by his assistants and pupils. In Stanza di Eliodoro, undoubtedly imposing is the fresco The liberation of Saint Peter. But it is Stanza della Segnatura that holds, in my opinion, the supreme work of this artist: The School of Athens. How to explain the grandeur of this painting? I can only think of an answer every time I see it: naturalness. Rafael creates this fresco in an imaginary space in time to highlight human wisdom, represented by Ancient Greece and recovered by Renaissance Rome. Plato and Aristotle are the main figures on it, on the way to the great arch, calm, solemn, before the gaze of Socrates. From all over, wise men: Euclides, Homer, Zoroastre. Funnily enough, as if in a joke, it is Rafael paints some of the faces of his contemporaries on relevant figures from the past. Plato’s face was that of Leonardo; Euclides’ face was Bramantes’s, Heraclitus’ face was Michelangelo, his rival! Rafael was a generous artist who recognized the talent of his adversaries. And The School of Athens reflects the faith of a good man in the hope that, while other contemporaries represented despair, e.g. Caravaggio, and often Michelangelo himself, the volcanic artist par excellence in the history of mankind, besides being a splendid painter, a sublime architect —Rafael also designed buildings— and a magnificent sculptor. His grandeur can, maybe, only be equalled by Leonardo. In Rome, one can track down his best works. The first of them all, of course, the sublime Vatican dome, classical lines, influenced by the Pantheon, and that this is the greatest in Christendom. If the power of popes —formerly political, now spiritual— has been one of the most sumptuous of the history of mankind, its best representation is the Basilica of Saint Peter, because of its esplanade, the imposing façade of its temple and the massive dome. And Michelangelo was one of its most renowned authors. Inside, there are two of the best examples of his flexibility: the Pietà, a marble sculpture representing the Virgin Mary crying over her dead son, a man too young to die; and the lavish Sistine Chapel, where one does not know whether it is God who takes the role of Manor it is Man who suddenly becomes God to deal the law of the Final Trial. We go up the staircase to San Pietro in Vincoli and admire the Moses that the artist carved on Julius II’s tomb. What energy from the guardian of the Tables of the Law! I see him, however, slightly scared about the burden of this responsibility. Michelangelo’s work does not stop there. There is the design of the beautiful Plazza del Campidoglio, with its solemn staircase and two beautiful buildings housing two museums of sculpture, one containing the beautiful equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, from classical Antiquity. There is also the façade to the harsh Palazzo Farnese, host to the Embassy of France. And the marbled Christ holding a cross before the major altar of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva.

Rome is much more than Michelangelo. Every day, I have to wander around this open-air museum to admire, for example, its Baroque legacy. Bleak Caravaggio is present in at least three Roman churches and museums of Villa Borghese and Palazzo Barberini. To admire the gifted sculptor and architect Bernini, you must go through many squares and other palaces and villas. As regards Spanish painter Velázquez, to witness some of his work means going to Gallery Doria Pamphili and shiver at the perverse look on pope Innocent X’s face. Nearly two days are needed to go through all the scenarios where the great Borromini designed the buildings, both religious and civil, or design his façades and interiors: the palaces de la Sapienza and Falconieri, the Oratorio dei Filippini, Santa Agnese di Agone, San Juan de Letrán and this precious jewel of the “perspective” of Palace Spada. This gallery flanked by columns with a small patio and a statue in the background, more than an architectural work, is the game of reason, a trickery of sizes, a view supposedly real of something that is unreal. Like art itself. From the top, in Gianícolo, I look down on Rome at dusk. There is so much to discover. Rome is eternal because it never ends.