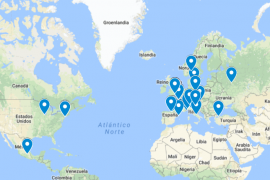

Inquisitive readers and [literary] devotees have a tool to entertain themselves with: a literary map of Barcelona, which compounds a great deal of information on the city’s heritage linked to the world of books. As a result of over a year’s labour, the map has just been published and it geographically locates the names and works of writers who have resided in Barcelona, those who have been associated with the city in some way or have written about it; sites and establishments they frequented, premises connected with the world of literature, libraries and bookshops… Most references pertain to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries—but also include [Shakespeare’s contemporary, ] Miguel de Cervantes or [18th century writer ] Baró de Maldà, for example. The map covers not only authors in Catalan and Spanish, but also in other languages.

Backed by Barcelona City Council—the Barcelona UNESCO City of Literature Office, headed by Marina Espasa—journalists and authors Víctor Fernández and Joan Safont have worked as “detectives” in order to track down the most intricate literary vestiges. At the presentation at La Central del Raval bookshop—the map is free, available at libraries, with copies in English at the tourist offices—featured some of the gems they have gathered, such as the fact that Anaïs Nin lived in Barcelona in 1916 because she had relatives here, at Carrer Roger de Llúria, 56; to find the address of [Majorcan writer] Miquel Bauçà they had to resort to the newspapers—he lived in Carrer del Marquès de Sentmenat; Antonio Machado stayed at the Torre Castanyer [mansion ] in Sant Gervasi; and Flaubert’s short story Bibliomanie was set in the Plaça Reial. The research went through many stages, for example when Fernandez asked his mother-in-law to help find the premises [Catalan author and translator ] Gabriel Ferrater frequented in Sant Gervasi. If the reader-amblers of this map are set on finding the writers’ eateries and watering holes, they will discover that amongst the patrons at the Hotel Cuatro Naciones in La Rambla were Stendhal, George Sand, and Pirandello.

Just to get an idea of the dimensions of the map, here are a few figures: 68 writers, 24 literary works related to Barcelona; 63 literary elements, including statues, tombs, literary locations, sources for writers, bars, hotels etc; 43 libraries, both public and specialised; 67 bookshops, including those selling children’s or second-hand books, as well as those at old-book markets; and ten quiet places where to read.

Just to get an idea of the dimensions of the map, here are a few figures: 68 writers, 24 literary works related to Barcelona; 63 literary elements, including statues, tombs, literary locations, sources for writers, bars, hotels etc; 43 libraries, both public and specialised; 67 bookshops, including those selling children’s or second-hand books, as well as those at old-book markets; and ten quiet places where to read.

It was of course necessary to establish certain criteria—such as the representative nature or the type of location that was important, and to make a selection, among other points because it was not materially possible to fit everyone on the map. For example, except for Vargas Llosa, who is a Nobel laureate, the only writers who appear in thumbnails are those who are already deceased, like Francisco González Ledesma—whose widow was at the presentation—Ana María and Terenci Moix, Sempronio, Palau i Fabre, Rosa Maria Arquimbau, Cèlia Suñol, Arthur Cravan—drawn with a boxing glove, appealing to the mystery that surrounds him—Jordi Sarsanedas, George Orwell, Roberto Bolaño, Rubén Darío, Irene Polo, Montserrat Roig or Pere Quart. Of the living authors, the addresses of their homes are not included for obvious reasons. The map establishes curious associations with neighbours, such as that between Josep Pla, located at the University of Barcelona, the setting at the beginning of his El quadern gris, and Carmen Laforet, whose novel Nada is set two streets along.

The idea is that this inventory of Barcelona’s heritage is a step towards recognising it, as has happened in cities like Paris, replete with plaques that recall its men and women of letters. “The idea is that people take the map and go and buy the books,” emphasises Marina Espasa. The distribution of literary material on the map is unavoidably disparate: “The centre of Barcelona appears to be crammed with writers, which is to be expected since it is the cradle of the city. But then there are other outlying districts that have been a pretty big surprise, like the neighbourhood of Vallcarca or the Coll district,” commented Joan Safont. Sarrià, with [native poet ] JV Foix and the writers of the [Latin-American literary] boom, is another focus point. And instead, the Eixample or the newly created neighbourhoods are rather empty. “We tried to be as accurate with everything as we could,” adds Víctor Fernández.

There have already been a few attempts of refutation on Twitter, as is usual with maps of this nature. Another aspect that must be taken into account, as Joan Safont points out, is that some street numbers may have changed since the residents referred to lived there.

Besides being available in print, the map can also be found on the website of the Barcelona City Council( http://ajuntament.barcelona.cat/ciutatdelaliteratura/en/literary-routes) where you can download seven literary routes for the city and a couple of projects that are now just beginning to bud: installation of poetic intercoms, devices at strategic points where poems can be heard, the first of which is to be installed at L'(H)original —now La Rubia—and at the Barcelona stand at the Buenos Aires book fair; and the literary footsteps project, marking the spaces that have inspired literary works with Panot paving stones. Footsteps that seek, after all, to promote the literature underfoot.