[dropcap letter=”T”]

he floral motifs, the structure of the domes or the shapes of the waves can seem recurrent topics in the painting, with no further interest. But in the hands of Najia Mehadji (1950) they become something else. If someone runs away from the commonplace that is this Franco-Moroccan artist, who lives and works between Paris and Essaouira. The retrospective exhibition dedicated to her by the Museum of Modern Art of Céret, La trace et le souffle (“The trace and the breath”), is a fresh breath of liveliness and intensity: a power that is expressed through the fixation of architectural structures, the vegetal world, the folds and games of clothes and waves. Loaded with authenticity, she is able to provide all these elements with a renewed vibration, a rhythm that surprises and shakes. The 150 pieces that make up the show seem to take the visitor’s hand and make him turn and dance like Camille Claudel’s sculpture La Valse, which works as an inspiration for some paintings.

Going through and understanding the skill of the artist’s inspiration is one of the great values of the route proposed by the exhibition, which can be visited until November 4th. Curated by the director of the Museum of Modern Art of Céret, Nathalie Gallissot, this is the first retrospective dedicated to Mehadji. Despite being little known in Spain, she has a long history and work distributed in prominent public and private collections, and in museums such as the Center Pompidou and the Arab World Institute of Paris or the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art Mohammed VI of Rabat. Four years ago, Ceret had already discovered a part of Mehadji’s work with the exhibition Le peintre et l’arène.

It is a work that is impregnated with references from the East and the West, to which it pays tribute and spreads them thanks to multiple rediscovered techniques and forms. The exhibition manages to reflect the internal coherence of her production. Following the thread of the influence exerted by the architecture of Le Corbusier and the oriental one, old drawings are exhibited (from a mosque in Algiers, the Alhambra in Granada, the Basilica of Saint Sophia…) that allow us to contemplate with a better perspective the paintings of the French-Moroccan artist. Later, a picture of El Greco (El espolio) will show; also, the films Ordet (by Carl Theodor Dreyer) and La danse serpentine (by the Lumière Brothers), the dance of the dervishes (a Turkish dance where they dance on themselves to ecstasy) or sub-Saharan gnawa soul music. This is how diverse are the artistic relationships that she establishes, relations in which, as can be seen, the movement and the folds of clothing stand out. These are her vital signs. With particular skills and a steady step, her pictorial universe delves into the capture of the movement’s dynamism. A movement that often rises with symbolic, spiritual sense, that exhales voluptuousness all-around.

Mehadji’s work realizes the phrase of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze: “art is not about reproducing the forms but about capturing the forces”.

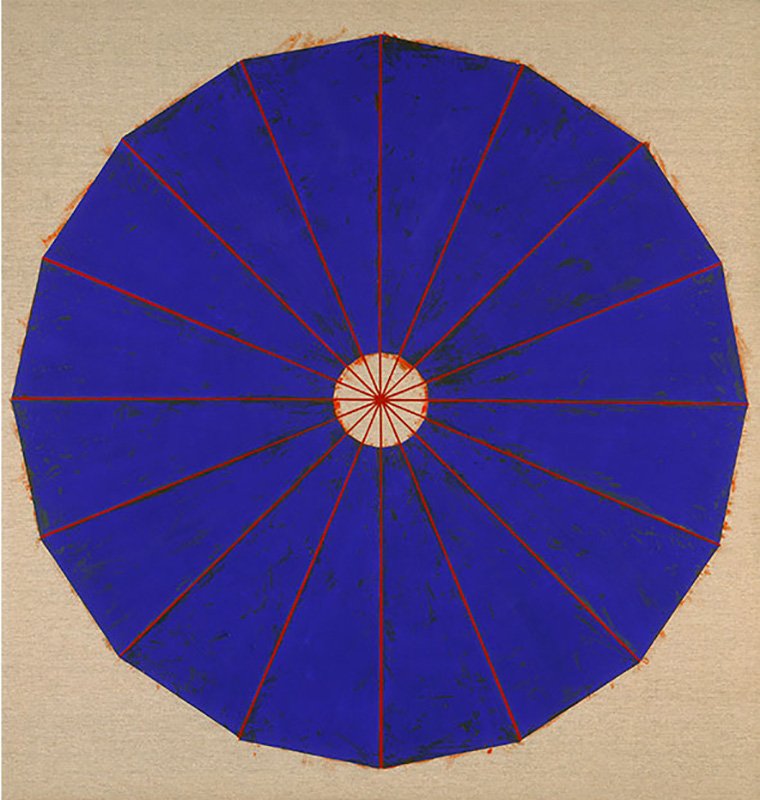

Everything seems to have its meaning and its motive in Mehadji. In a video at the end of the exhibition, the artist explains that a series of paintings of domes was created as a result of the impact of the Bosnian war, in the 90s. Being attracted by the drawing of lines in space, the relationship between volumes and forms of nature, thus the first part of the exhibition plays with domes, rhombuses, plans and surfaces within the painting, and expresses all the best of the floral forms, as a symbol of beauty and also of the fragility and brevity of the lifetime. Blues, reds, yellows, garnets, blacks… They are often blunt colors, occasionally sparse. She plays with your look, with the effects of perspective, and invites you to look and find new centers of attention, where it seemed that there were none.

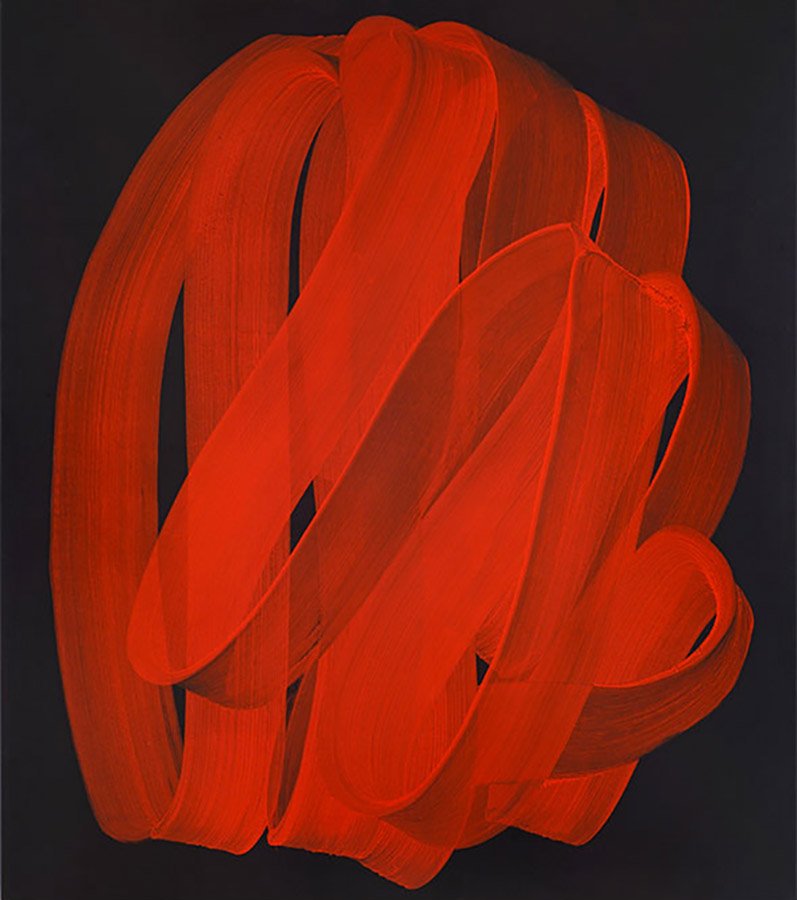

The different series (of domes, of flowers, of waves…) encapsulate a movement and a meaning that grows and branches out. For example, in the series dedicated to the flower of the pomegranate, mystical and mythological flower of Asian origin, the results are spectacular. The same goes for wave paintings -often with incisive titles- where you have no choice but to merge with the force of a precise and enigmatic gesture at the same time, of an exultant naturalness. Mehadji’s work realizes the phrase of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze: “art is not about reproducing the forms but about capturing the forces”. This is especially evident in the series of pictures of waves and buds, that has a hypnotic magnetism. This succession of paintings, perhaps the most surprising of all, takes to the extreme the feeling of movement; as if density, speed and depth did not stop moving inside the painting, as if it were not a fixed object inside an exhibition hall. Mehadji does just like the child who takes a tape and moves it up and down capriciously, generating different effects and impacts: the shapes in contortion, the vitality exploding or drowned, give a kinetic energy that changes direction. The Goyesque Suite, dedicated to the disasters of the war shows a burned yellow color, and seems different from this group, but it is still of a disturbing forcefulness.

With so much dynamism around, it is perfectly understandable that, as a closure of the exhibition -proposed by the center- Mehadji chose Picasso’s Sardana de la Paz, the piece of the permanent collection that links best with her work. One more example of the free spirit that works as a motor. And a reminder for those who do not know the Museum of Modern Art of Ceret: it hosts works by prominent artists who passed through the capital of Vallespir, such as Picasso, Manolo Hugué, Arístides Maillol, Miró, Juan Gris or Marc Chagall. The Mehadji exhibition is open until November 4th.