[dropcap letter=”A”]

ll civilizations, from the Egyptians on to the present, have always been more interested in carrying out grand performances that would be appreciated by all their subjects, rather than those that cannot easily be observed and admired. The Pyramids, the Christian temples, the Colosseum, the Roman pantheons or the French Panthéon, the great architectural works of industrial Europe or the Universal Exhibitions reveal the secret inclination of men for great human achievement. Many of these constructions had the purpose of bending human will to mysterious forces in order to protect their lives, such as in ancient Egypt or in the Europe of the Middle Ages. Others have been erected to show the power of a country, such as the park created in 1939, an icon of the explosion of the achievements of the Soviet economy, today known as the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy, where visitors can contemplate a giant rocket launcher and bewildered, as if they were Charlton Heston in Planet of the Apes, face the prospect of returning to the political conditions of a new Cold War.

The fascination with grandeur, that which reduces man to a dot on a map, has the atomic bombs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki as the pinnacle of representation of this monumental human scenography. The atomic bomb has become an iconic aesthetic of the horror of the limits that must not be exceeded by the achievements of humans. The conquest of space in their spaceships and the immense darkness that surrounds them is another image that leads the human spirit to greater interest in looking through a telescope than into a microscope. The forces that dominated the end of the nineteenth century and the twentieth century have been more focused on inquiring into the great than the small; energies put to the service of great wars, of genocides or nuclear disasters such as Chernobyl. The tsunami in Indonesia or the Mexican earthquake have a greater effect on our psyche than the thousands killed by HIV/AIDS. The immense magnitudes leave a deep gouge in our memory, while small or individual ones are forgotten or simply ignored. This tendency to fascination by the great into which western culture has been immersed in the Twentieth Century has begun to change in the Twenty-first, where human efforts are concentrating on great small things, such as genetics or microbes.

In his fascinating book, The Gene: An Intimate History, science communicator Siddhartha Mukherjee puts us on the trail of a human adventure dating back to the end of the 19th century, and which is now beginning to acquire meaning and potential concerning the study of genetic manipulation and commerce. The author explains how in 1962, when DNA’s triplet code had just been sequenced, The New York Times published an article on “the explosive future of human genetics.” Now the code had been revealed, The New York Times predicted the possibility of subjecting human genes to any intervention. “It is safe to say that some of the biological ‘bombs’ that are likely to explode before long as a result of [breaking the genetic code] will rival even the atomic variety in their meaning for man. Some of them might be: determining the basis of thought… developing remedies for afflictions that today are incurable, such as cancer and many of the tragic inherited disorders.” In a way, the prediction of The New York Times is beginning to be fulfilled just as we take in that it is possible to be repaired, cured or have our genetics enhanced. The genetic bomb clearly states that the cosmos that we long to discover is within us and not in the confines of space. This signifies a leap into the interior, towards the small, which alerts us to the fact that, if we are concerned about the future, our children will be worried about the future of the future. It is imperative to know who we are to deal with the futures we are aiming for as a species but, above all, we do not want to miss out on anything that concerns our health and our quality of life. As Rosi Braidotti explains in her essay The Posthuman, the genetic journey opens the door to a posthumanism that establishes that “technologies actively contribute to the way humans develop ethics.” In the same way, in grasping that the explosion of the small is changing the way we are in the world, we find in the surprising study by Ed Young I Contain Multitudes, that he observes the microbes that inhabit us as a broader way of seeing life. Ed Young says that “microbes have always ruled the planet, but today, for the first time in history, they are in vogue.” Biologist Margaret McFall-Ngai appreciated that “it has been fun to see how people begin to realize that microbes are the centre of the universe and how this field is begining to bloom. Now we know that they constitute the great diversity of the biosphere that lives in close association with animals, and that animal biology was shaped by interaction with microbes. In my opinion, this is the most important revolution that biology has gone through since Darwin.” Now we have shown that microbes control the storage of fats and the formation of new blood vessels, we are on the path to discovering how the management of the microbiomes will affect our way of life. In Amsterdam, Micropia is the first museum in the world dedicated to microbes. Visiting it shows us that the apparently small is so important and determining in our lives that it rises before us as new cathedrals that will even alter our beliefs.

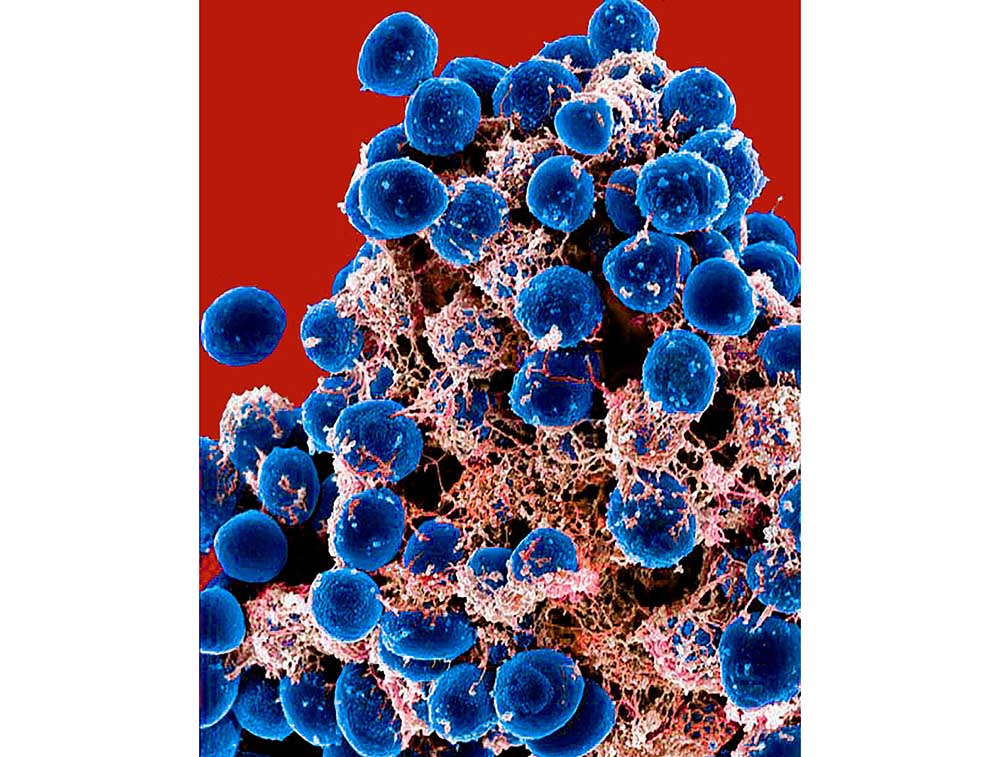

Featured image:

Electron micrograph of bacteria Staphylococcus epidermidis in extracellular matrix.