In early October 2003, the streets of Tallinn, capital of Estonia, it was still possible to decipher the several Soviet symbols carved in stone, architecture and people’s faces. After leaving an Orthodox church from the city center, 3 old ladies, wrapped up in their clothes, begged while showing their hands covered in fingerless woolen gloves. When they heard us speak in Catalan, one of them shouted: no passaran! in memory of the International claim against fascism. Nobody should wonder what episodes from her life prompted her to pronounce such iconographic words because political tremors, just like environmental disasters, are ingrained in collective imagery, biographies and memories under layers of inert material in a place where time stands still. Not too long after, I experienced a similar situation while looking for a place to protect myself from the blistering cold weather that, at this time of year, was showing its fierceness. Walking through an antique shop displaying its products within a rusty metal structure with pieces of broken glass or no glass at all, a merchant offered me an album with Soviet images commemorating the 50 years of the Russian Revolution of 1917. He talked me into it and, by way of compensation, gave me a set of military passports from that time, physical description, names, stamps; tips of frozen information, as if they were iceberg tips from that time. I wondered who those people might have been.

In May 1965, during the Cold War’s space conquest, Serguei Koroliov, the head Russian cosmonaut engineer, rescued from a gulag 4 year before completing his forced labor sentence, was assigned the task of sending man to the moon to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Revolution. The works by Koroliov with the N1, the space machine that would consolidate the victory from Eastern Europe, obtained a small fraction from the budget assigned by the Kennedy’s administration to the same project in the US. A year later, on 27 January 67, the Americans launched Apollo 1. His was a mere training mission before consolidating the achievement of landing on the Moon, two years later with the Apollo 11 expedition led by Armstrong. But Apollo 1 failed. The spacecraft blew up a few seconds after lift-off. This unfortunate accident plunged the whole aerospace program led by Verner Von Braun, Koroliov’s American counterpart and former Nazi SS officer, into a deep crisis.

In a scene of total sadness, the team of engineers allow the astronaut, still alive in a ship out of control, to say goodbye to his wife on the phone

Three months later, the Russians also tried to bring forward an equally risky mission. They managed to put the ship on orbit but, unfortunately, one of the solar panels failed and caused problems in the re-entry system. In a scene of total sadness, the team of engineers allow the astronaut, still alive in a ship out of control, to say goodbye to his wife on the phone. Despite the astronaut’s attempts to re-direct the ship and enter the earth’s atmosphere, at the last minute the parachute failed and fell to the ground. One year later, in March 1968, Yuri Gagarin died when the fighter jet he was piloting crashed due to uncertain circumstances. Gagarin, the son of the people and of parents who grew up in a collective farm, one of the icons of Soviet space travel. On 12th April 1961, Gagarin proudly headed for the metal steps of the ship. He was being escorted by a group of grey engineers, the only ones aware that the odds of surviving this endeavor were only slightly higher than 50%. Minutes later, the calm voice of the astronaut in the radio waves contrasted with the hysterical rhythm of the hands of the clock of the control room from the Russian station. At the time, it was ten past nine in the morning, and Gagarin was watching the Earth from the Vostok, the first manned spacecraft orbiting the planet, the first shell that managed to bring time to a standstill.

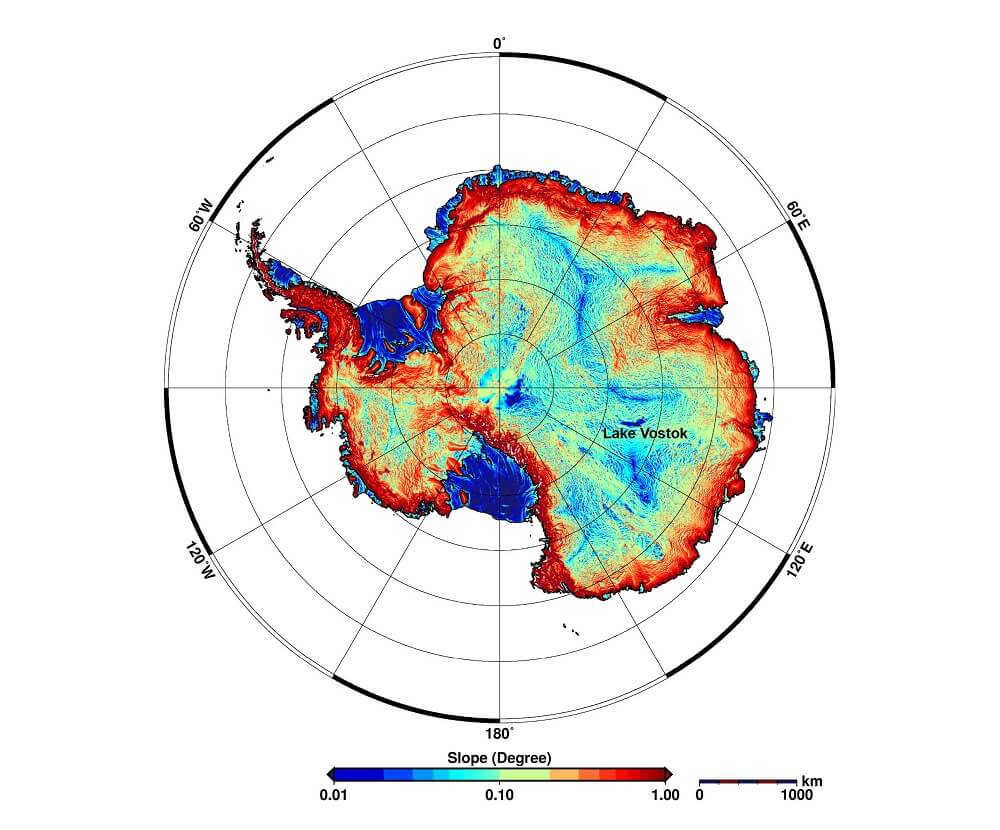

Months before, Tallinn celebrated its 50th anniversary by waking up on the other side of the Iron Curtain to the rhythm of jazz. Also, that same year, in 1967, a team of Russian scientists led by Andrei Kapitsa concluded an unprecedented discovery. Lake Vostok was found underneath approximately 5,000 meters of Antarctic ice, a place where time stood still 30 million years ago. Kapitsa never went back to the Antarctic. But studies have progressed since then, and there are voices who claim that the lake, one of the biggest of the planet, existed before the formation of the ice caps, back when the Antarctic was a warm place and the Vostok was surrounded by lush forests. The scientists suggest that time trapped in the shape of microorganisms could help us understand how life was formed and, therefore, would give us evidence of the circumstances that made life possible, and thus apply them to other planets and stars, and so the race, as could be expected, is already on the way.

Featured images:

1. Soviet Vostok rocket launcher at the Paris air show. May 1967. Photo by Keystone Pictures USA / Alamy Stock Photo

2. Thermal map of Antarctica indicating the location of Lake Vostok.

3. Seals of Cosmonauts and spacecraft of the USSR, 1971. Ship Vostok, Yuri Gagarin, first man to tread the moon and first orbital station. Scanned by Matsievsky from the personal collection. Wikimedia Commons

4. Soviet cosmonaut and first man to go into space, Yuri Gagarin 1961. Photo by ITAR-TASS News Agency / Alamy Stock Phot