The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

You would never say that Mari Carmen Tous is 85...

In critical times, it is fair to determine the relevance...

The New York Times, with a total of 125 awards,...

Barcelona, with 20.33 million overnight stays, led in 2016 the...

Would you like to walk around with the Giocconda under...

Take a deep breath. Alright? We are going to talk...

The dFactory Incubator centre, capable of providing services simultaneously to...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

Since the Walkman we have walked from one place to...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

It is true that we are beginning to put the financial crisis behind us, and that many indicators show economic recovery is well under way. But nearly a decade of recession doesn’t end without leaving scars, and this one has left quite a few that will take some time to heal, or may even last forever. The health of the so-called middle class is one of the victims of the crisis. All indicators show that this group (generally defined as households with a yearly disposable income between two-thirds and double the average income) has been seriously eroded over the years of the recession. In other words, this means it has lost volume and weight as a percentage of the population. The middle class today is a bit less “king” that it was a decade ago.

Between the richest 10% and the poorest 25%, the middle class has lost ground and now uses most of its income to cover housing expenses.

According to data from the latest Survey of Household Finances by the Bank of Spain the average income of Spanish households dropped 9.7% between 2011 and 2014, when the first signs of economic recovery were noted. At the same time, indications of inequality rose, with a greater concentration of wealth in the higher classes and the lowest income groups growing. And so, the middle class has dwindled. According to the same report, 52.8% of all wealth in Spain was held by the richest 10% of households in 2014. In fact, the wealthiest 1% went from holding 16.87% in 2011 to having 20.23% three years later. On the other hand, according to the Bank of Spain data, 25% of the poorest households had more debt than assets in 2014, with a negative net worth of €1,300 on average.

Between the richest 10% and the poorest 25%, the middle class has lost ground and now uses most of its income to cover housing expenses. This is the result of years of high unemployment and falling salaries that have nullified the serious drop in prices in the real estate market. Now these prices are starting to go up again, but salaries aren’t yet, which means part of the middle class that was managing to stay in the black could end up further swelling the ranks of the lower class.

The impact of the recession has been decisive in altering the socioeconomic map of the country, and one of the clearest effects has been the three million individuals that have been reclassified from the middle class to the most vulnerable social stratum.

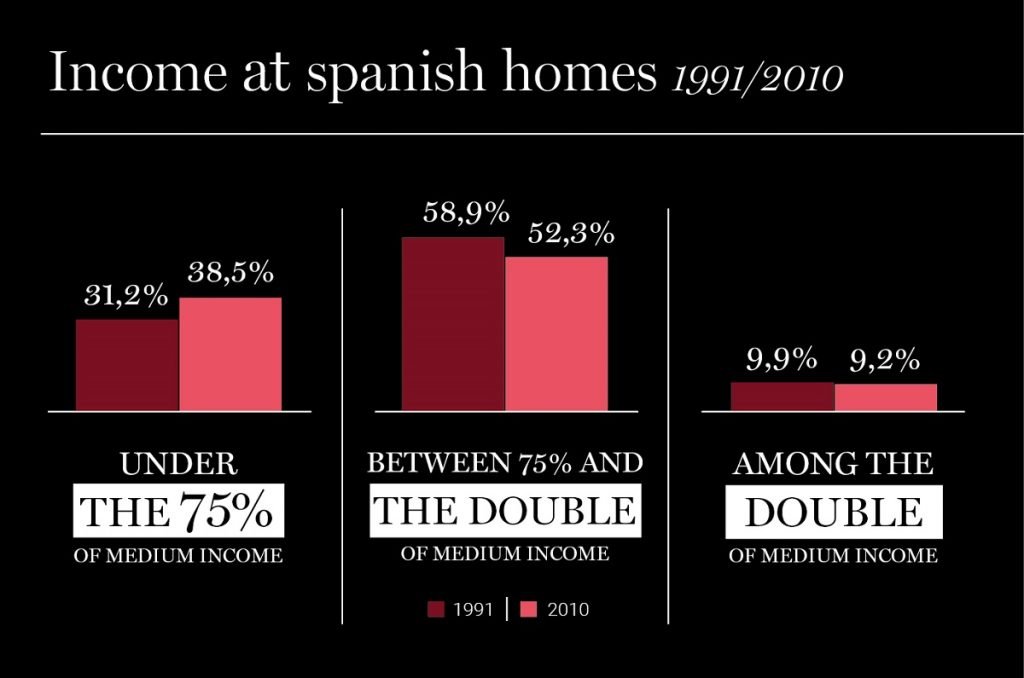

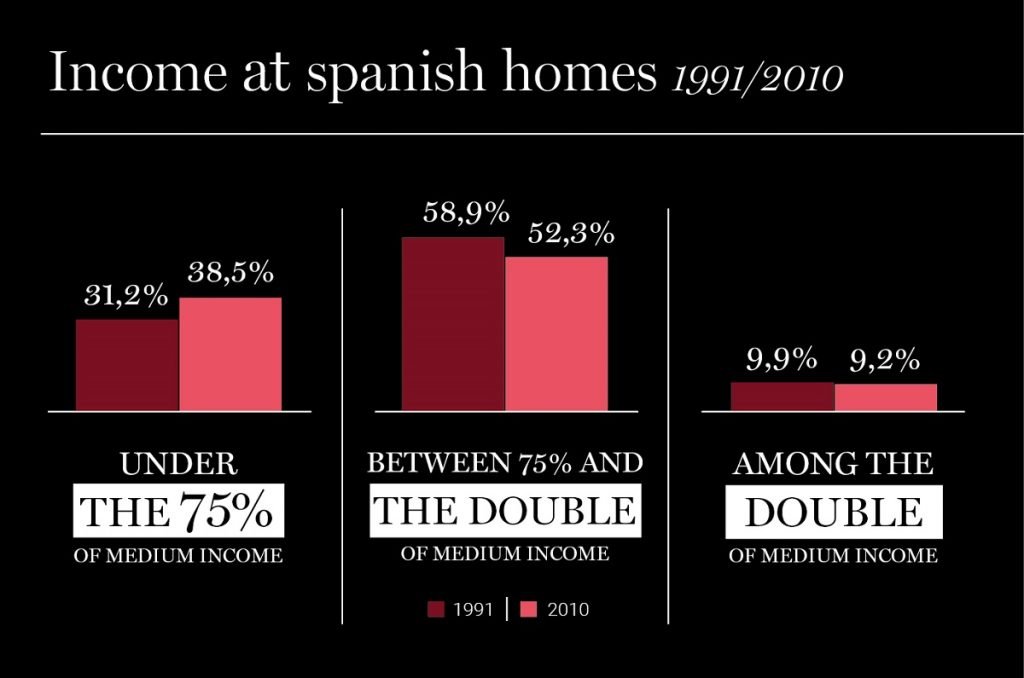

This erosion of the middle class noted in the Bank of Spain Survey of Household Finances 2011-2014 comes on top of the ground this social class had already lost in the early years of the recession. This effect can be clearly seen in the data report Distribución de la renta, crisis económica y políticas redistributivas (Distribution of income, recession and redistribution policies) compiled by the BBVA Foundation and the Valencian Institute of Economic Research (Ivie) that analyses the decade between 2003 to 2013. According to this report, disposable income in Spanish households fell 20% over that time. In fact, the impact of the recession has been decisive in altering the socioeconomic map of the country, and one of the clearest effects has been the three million individuals that have been reclassified from the middle class to the most vulnerable social stratum. The figures speak for themselves. In 2003, according to the study, 59% of the Spanish population belonged to households within the middle band, meaning those earning 75% to 200% of the average income, and 31% were below this line. Ten years later, these figures had changed to 52% and 39%, respectively.

The fact that the majority of family’s disposable income (75%) comes from salaries and these have dwindled or disappeared completely due to the massive increase in unemployment explains, according to the report’s authors, this significant change.

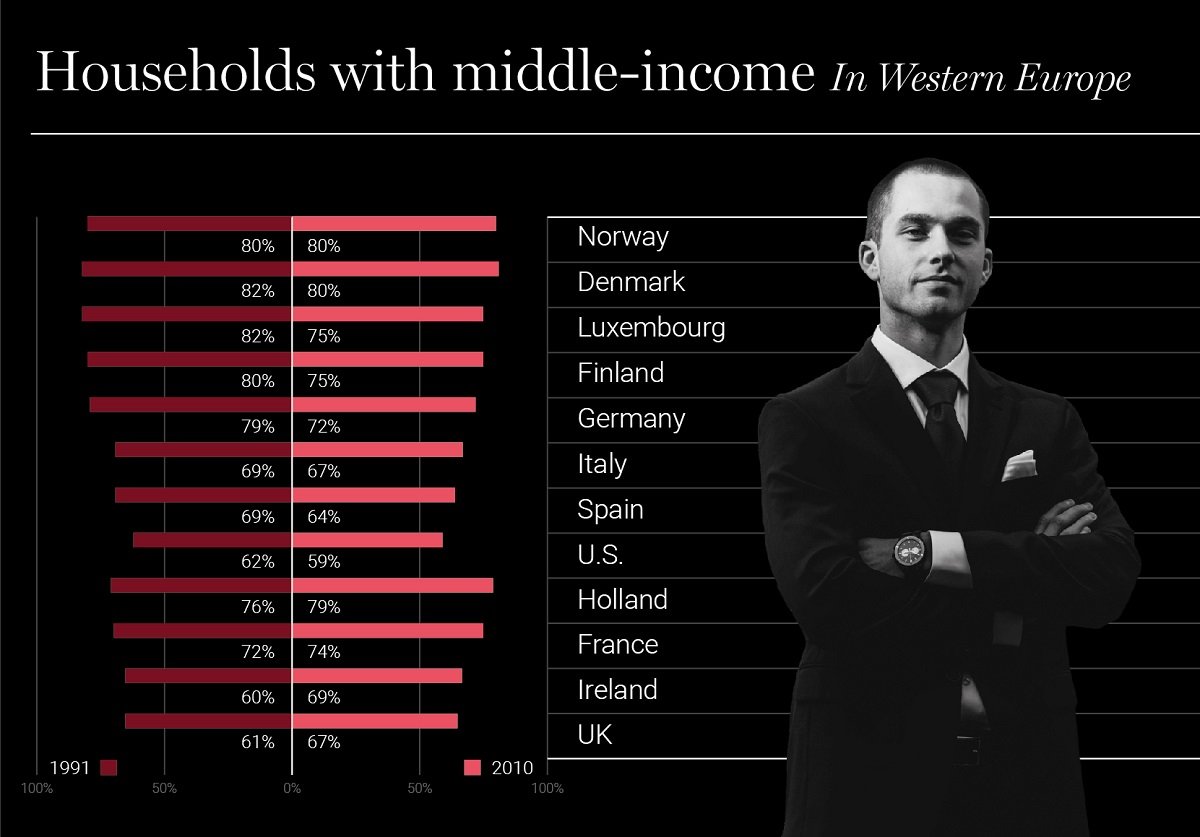

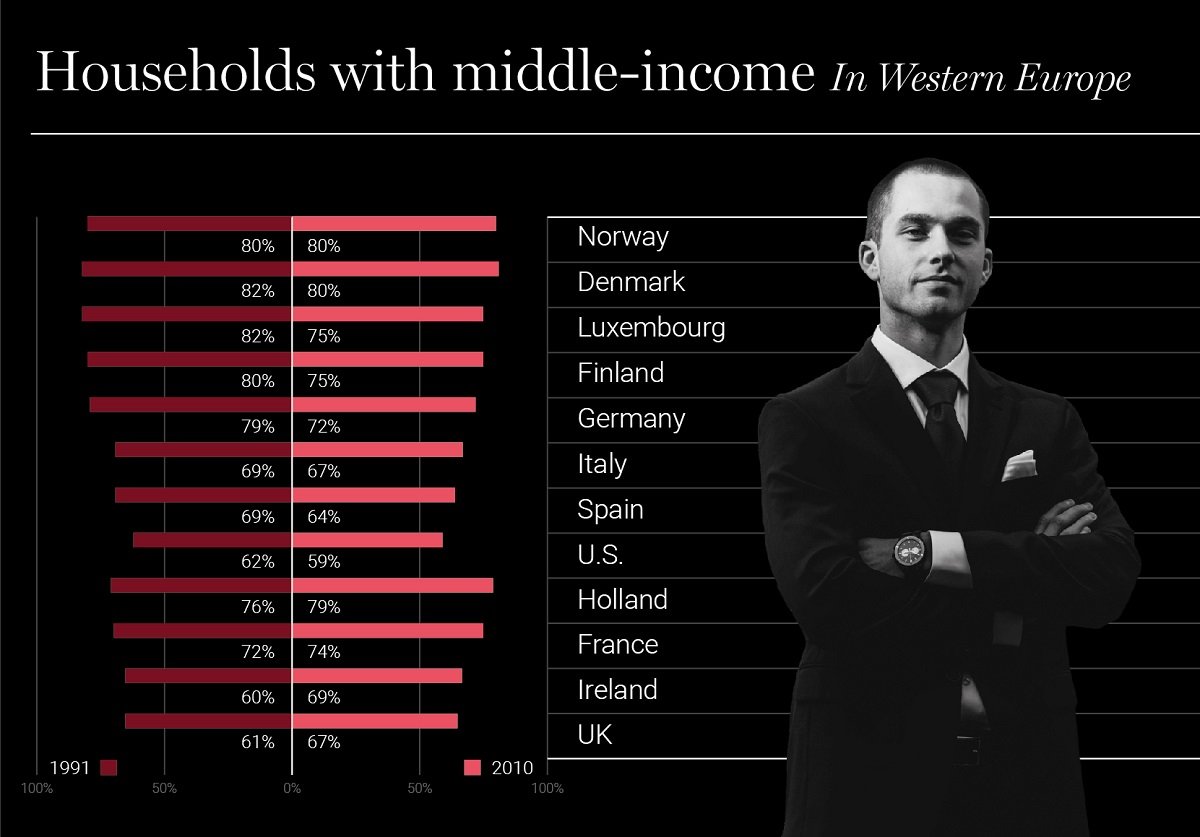

And although the recession didn’t only affect this country, if you look at the data from US think-tank Pew Research Center (PRC), Spain suffered this impact on the middle class more than nearly any other country in Europe. According to this centre, between 1991 and 2013, the erosion of this group was worrisome, going from 70% to 60% of all households, compared to a more moderate decrease or even an increase over the same period in other European countries such as France and the Netherlands.

In recent years, the International Monetary Fund has also stressed the need to promote recovery of mid-level earners in advanced economies to avoid a crisis of the middle class that would slow economic recovery.

According to the PRC, which agrees with the OECD on this topic, we would have to look to the United States to find a smaller middle class. The problem in Spain, as in the United States, has been increasing inequality over the past years. So, the lower class (which the study establishes as households earning less than $21,257 a year) made up 25% of the total in 2013, the highest percentage in the study, although it did not include Portugal or Greece. At the same time, the upper class made up 14% of the total, also considerably higher than other European countries, which explains why the group in the middle (the middle class) has become so small.

In recent years, the International Monetary Fund has also stressed the need to promote recovery of mid-level earners in advanced economies to avoid a crisis of the middle class that would slow economic recovery. The real question here is to know if what was lost over the years of recession can be recovered. Some figures point to a somewhat hopeful response. For example, according to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE), Spain’s AROPE indicator (at risk of poverty or social exclusion) was 28% in 2016, down from the all-time high of 29.2% in 2014. While it is still far above the 23.8% of 2008, this slight improvement seems meaningful.

We’ve seen a change in trend in the latest data on distribution of income from the Barcelona City Council, for 2016. According to these figures, the improved job market and decreased unemployment had begun to have an effect and the percentage of Barcelona residents living in neighbourhoods with average income was up that year from 44% to 47.8%.

We’ve also seen a change in trend in the latest data on distribution of income from the Barcelona City Council, for 2016. According to these figures, the improved job market and decreased unemployment had begun to have an effect and the percentage of Barcelona residents living in neighbourhoods with average income was up that year from 44% to 47.8%. All the ground lost here during the recession hasn’t been made up yet either (in 2007, it was 59%), but we are starting to see a shift in tide.

It is yet to be seen if the middle class will ever have the same proportional importance in Spain as before the recession, and if so how long it will take. The evolution of the job market and salaries will be key in this regard, as all the studies show. The efficacy of redistribution policies, as well. But in any case, the pace of recovery seems like it will be slow and need tools to decrease the inequality indicators.

It is true that we are beginning to put the financial crisis behind us, and that many indicators show economic recovery is well under way. But nearly a decade of recession doesn’t end without leaving scars, and this one has left quite a few that will take some time to heal, or may even last forever. The health of the so-called middle class is one of the victims of the crisis. All indicators show that this group (generally defined as households with a yearly disposable income between two-thirds and double the average income) has been seriously eroded over the years of the recession. In other words, this means it has lost volume and weight as a percentage of the population. The middle class today is a bit less “king” that it was a decade ago.

Between the richest 10% and the poorest 25%, the middle class has lost ground and now uses most of its income to cover housing expenses.

According to data from the latest Survey of Household Finances by the Bank of Spain the average income of Spanish households dropped 9.7% between 2011 and 2014, when the first signs of economic recovery were noted. At the same time, indications of inequality rose, with a greater concentration of wealth in the higher classes and the lowest income groups growing. And so, the middle class has dwindled. According to the same report, 52.8% of all wealth in Spain was held by the richest 10% of households in 2014. In fact, the wealthiest 1% went from holding 16.87% in 2011 to having 20.23% three years later. On the other hand, according to the Bank of Spain data, 25% of the poorest households had more debt than assets in 2014, with a negative net worth of €1,300 on average.

Between the richest 10% and the poorest 25%, the middle class has lost ground and now uses most of its income to cover housing expenses. This is the result of years of high unemployment and falling salaries that have nullified the serious drop in prices in the real estate market. Now these prices are starting to go up again, but salaries aren’t yet, which means part of the middle class that was managing to stay in the black could end up further swelling the ranks of the lower class.

The impact of the recession has been decisive in altering the socioeconomic map of the country, and one of the clearest effects has been the three million individuals that have been reclassified from the middle class to the most vulnerable social stratum.

This erosion of the middle class noted in the Bank of Spain Survey of Household Finances 2011-2014 comes on top of the ground this social class had already lost in the early years of the recession. This effect can be clearly seen in the data report Distribución de la renta, crisis económica y políticas redistributivas (Distribution of income, recession and redistribution policies) compiled by the BBVA Foundation and the Valencian Institute of Economic Research (Ivie) that analyses the decade between 2003 to 2013. According to this report, disposable income in Spanish households fell 20% over that time. In fact, the impact of the recession has been decisive in altering the socioeconomic map of the country, and one of the clearest effects has been the three million individuals that have been reclassified from the middle class to the most vulnerable social stratum. The figures speak for themselves. In 2003, according to the study, 59% of the Spanish population belonged to households within the middle band, meaning those earning 75% to 200% of the average income, and 31% were below this line. Ten years later, these figures had changed to 52% and 39%, respectively.

The fact that the majority of family’s disposable income (75%) comes from salaries and these have dwindled or disappeared completely due to the massive increase in unemployment explains, according to the report’s authors, this significant change.

And although the recession didn’t only affect this country, if you look at the data from US think-tank Pew Research Center (PRC), Spain suffered this impact on the middle class more than nearly any other country in Europe. According to this centre, between 1991 and 2013, the erosion of this group was worrisome, going from 70% to 60% of all households, compared to a more moderate decrease or even an increase over the same period in other European countries such as France and the Netherlands.

In recent years, the International Monetary Fund has also stressed the need to promote recovery of mid-level earners in advanced economies to avoid a crisis of the middle class that would slow economic recovery.

According to the PRC, which agrees with the OECD on this topic, we would have to look to the United States to find a smaller middle class. The problem in Spain, as in the United States, has been increasing inequality over the past years. So, the lower class (which the study establishes as households earning less than $21,257 a year) made up 25% of the total in 2013, the highest percentage in the study, although it did not include Portugal or Greece. At the same time, the upper class made up 14% of the total, also considerably higher than other European countries, which explains why the group in the middle (the middle class) has become so small.

In recent years, the International Monetary Fund has also stressed the need to promote recovery of mid-level earners in advanced economies to avoid a crisis of the middle class that would slow economic recovery. The real question here is to know if what was lost over the years of recession can be recovered. Some figures point to a somewhat hopeful response. For example, according to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE), Spain’s AROPE indicator (at risk of poverty or social exclusion) was 28% in 2016, down from the all-time high of 29.2% in 2014. While it is still far above the 23.8% of 2008, this slight improvement seems meaningful.

We’ve seen a change in trend in the latest data on distribution of income from the Barcelona City Council, for 2016. According to these figures, the improved job market and decreased unemployment had begun to have an effect and the percentage of Barcelona residents living in neighbourhoods with average income was up that year from 44% to 47.8%.

We’ve also seen a change in trend in the latest data on distribution of income from the Barcelona City Council, for 2016. According to these figures, the improved job market and decreased unemployment had begun to have an effect and the percentage of Barcelona residents living in neighbourhoods with average income was up that year from 44% to 47.8%. All the ground lost here during the recession hasn’t been made up yet either (in 2007, it was 59%), but we are starting to see a shift in tide.

It is yet to be seen if the middle class will ever have the same proportional importance in Spain as before the recession, and if so how long it will take. The evolution of the job market and salaries will be key in this regard, as all the studies show. The efficacy of redistribution policies, as well. But in any case, the pace of recovery seems like it will be slow and need tools to decrease the inequality indicators.